METHOD OR MADNESS?

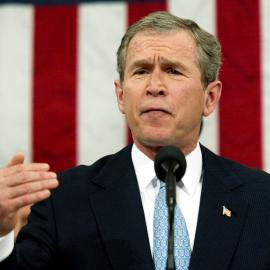

On January 29, President George W. Bush announced what seemed a new U.S. policy toward the Korean Peninsula—and threw observers worldwide into confusion. In his state of the union address that night, Bush outlined the steps to come in his administration's "war on terrorism." Among them was a tough new approach to what he termed an "axis of evil": North Korea, Iraq, and Iran.

The president's speech seemed, at first, to bring new clarity to the U.S. security agenda, signaling the high priority the administration placed on countering links between terrorists and rogue nations that seek chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons to threaten the United States and the world. The only problem was that, at least with respect to North Korea, this new posture seemed to contradict the strategy suggested by the Bush administration seven months earlier. In June 2001, a comprehensive policy review authorized by the White House had recommended that Washington hold unconditional talks with Pyongyang on a wide range of issues, including the posture of North Korea's conventional military, its ballistic missile program, and its suspected nuclear weapons program.

This recommendation, in turn, had been at odds with a previous set of Bush remarks on the subject. In March 2001, he had scorned the "sunshine," or engagement, policy of South Korea's president, Kim Dae Jung, and expressed skepticism about North Korea's supposedly peaceful intentions. And these remarks, finally, had broken with still another proclamation of U.S. policy—this one by Secretary of State Colin Powell, who had announced earlier the same month that the Bush administration intended to pick up negotiations with North Korea where the Clinton administration had left off.

In light of these zigzags, it is hardly surprising that Bush's state of the union address caused a lot of head-scratching. And indeed, several months afterward, for many the question remains: Does the administration know what it is doing on North Korea? Does it actually have any policy at all, or is the topic a football grabbed by whichever internal faction has the president's ear at a particular moment?

These questions are of more than bureaucratic interest, for a confluence of trends suggests that the situation on the Korean Peninsula will not remain quiet for long. U.S. relations with North Korea are currently guided by the 1994 Agreed Framework, in which Washington offered heavy fuel oil and help building nuclear energy plants in exchange for Pyongyang's promise to shut down its nuclear weapons program. This agreement is about to reach its critical implementation stages, testing the intentions of both countries and sparking debates within the United States over whether it should revise or abandon the accord. Engagement, meanwhile, has already become a hotly contested issue in South Korea, where the upcoming presidential election in December 2002 has led to acerbic criticism of Kim Dae Jung's policy by his most prominent harder-line opponent, Lee Hoi Chang. Complicating matters still further, normalization talks between Japan and North Korea have remained frozen since the winter of 2000, and Pyongyang's rhetoric about Tokyo is growing ever more aggressive. International aid workers are projecting another food shortage in North Korea, just as donor fatigue is setting in. And most ominously, North Korean leader Kim Jong Il's self-imposed moratorium on ballistic missile tests also ends this December. Experts argue that the North is most belligerent when it has nothing to lose. If they are right, some kind of crisis looks likely on the Korean Peninsula, and so having a clear and well-thought-out policy in place could be critical.

Bush's critics argue that there is a serious gap between the new "axis of evil" language and the substance of U.S. policy toward North Korea. At best, they argue, the divide reflects Bush's unwillingness to admit openly that Bill Clinton's effort to engage Kim Jong Il made sense. At worst, the "axis of evil" puts the administration on a collision course with North Korea during the second phase of the war on terror.

In fact, however, the critics are wrong on both counts. The president's speech involved neither the unceremonious dumping of the engagement strategy nor a simple desire to distinguish himself from Clinton while actually following in his footsteps. A close reading of the state of the union address and other administration moves suggests that the Bush team is stumbling, in its own peculiar way, toward an approach to North Korea that is neither the twin nor the opposite of his predecessor's, but rather a buffed-up cousin. And when the dust settles, most people—including the administration, its critics, and the general public—might just realize how well-suited this strategy is to the complex realities of North Korea.

"Hawk engagement," as one might call the administration's developing approach, differs from traditional models more in its philosophy than in its practice. It certainly stands apart from South Korea's sunshine policy, but less by its short-term execution than by its assumptions, rationales, and potential endgames. Kim Dae Jung, as well as some Clinton officials, sees engagement as a way to build transparency and confidence and reduce insecurity. Hawk engagement, on the other hand, is based on the idea that engagement lays the groundwork for punitive action. Hawks are skeptical that North Korea can be induced to cooperate but are willing to use engagement to call Pyongyang's bluff. The goal of the sunshine policy, furthermore, is limited to achieving peaceful coexistence between the two Koreas. Hawk engagement, in contrast, offers a true vision of how to shape the future of the Korean Peninsula in a way that best suits America's larger strategic interests—both during unification and beyond.

HAWK ENGAGEMENT

The Bush team claims that there are five elements in its new policy that are distinct from Clinton's: insistence on improved implementation of the Agreed Framework; verifiable controls on the North's missile production and exports; a way to address the posture of conventional forces; a demand for reciprocal gestures in return for compromises with the North; and close coordination with allies. Only one of these components—the focus on conventional forces—is actually new. All the others had been discussed by Clinton's Korea policy blueprint (created by former Defense Secretary William Perry in October 1999) and in the Republicans' own blueprint (penned by Richard Armitage, now deputy secretary of state, in March 1999). But there are other differences between Bush's view of North Korea and Clinton's that are even more important.

Bush's emerging strategy of hawk engagement can best be understood by juxtaposing it with the standard rationale for engagement with the North, exemplified by Kim Dae Jung's sunshine policy. Kim's strategy rests on the idea that North Korea's threatening posture arises from insecurity. Abandoned by its Cold War patrons, economically bankrupt, politically isolated, and starving, North Korea sees the pursuit of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles as its only path to security and survival. Engagement can reduce this insecurity and end the proliferation threat. Various carrots—economic aid, normalized relations, reduced security tensions—are supposed to give Kim Jong Il a stake in the status quo and persuade him that he can best serve his own interests by giving up on the pursuit of dangerous new weapons.

Hawk engagement breaks with this logic in several respects. It acknowledges that diplomacy can be helpful, but sees the real value of engagement as a way to expose the North's true, malevolent intentions—thought to include not just the desire to develop nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons, but ultimately to expel U.S. forces from the peninsula, overthrow the regime in Seoul, and reunify Korea under communist rule. Hawk engagement aims to thwart these goals by dealing with Pyongyang in the near term but also laying the groundwork for punitive actions against it later on.

Supporters of the sunshine policy view engagement as the best way to discern and improve the intentions of the reclusive Kim Jong Il today. Hawks, however, see engagement as the best practical way to build a coalition for punishment tomorrow. Such a coalition is critical to putting effective pressure on the North, but maintaining it will require its members to agree that every opportunity to resolve the problem in a nonconfrontational manner has been exhausted.

Recent history shows just how important it is to assemble and maintain such regional support for action on North Korea. In 1994, when the North refused to comply with international inspections of its nuclear facilities, the United States sought to impose sanctions on it. But the sanctions were resisted, not only by China (which would have vetoed any attempt to impose them through the UN Security Council), but also by Japan, which was reluctant to curb remittances to the North from Koreans in Japan and argued that such a coercive strategy was premature.

Hawk engagement provides a way to convince allies that noncoercive strategies have already been tried—and failed. As the Armitage report explains, "the failure of enhanced diplomacy should be demonstrably attributable to Pyongyang."

Hawk engagement would also let the United States turn today's carrots into effective sticks for tomorrow. Merely continuing to impose the more than 50-year-old embargo on North Korea, for example, is unlikely to lead to a change in its behavior. Were Washington to lift sanctions, however—letting the North get a taste for what it could gain by cooperating—then a threat to reinstate the sanctions would likely have a much more dramatic effect. Indeed, this pattern has already played out at least once. In June 1999, North Korea detained on spy charges a citizen from the South who was visiting Mount Kumgang as part of a new inter-Korean joint tourist venture conducted by Hyundai, a South Korean conglomerate. Seoul retaliated by suspending further tours. These tours, however, represented a new and substantial source of hard currency for the North. Pyongyang quickly realized that the propaganda value of capturing a supposed spy from the South was vastly outweighed by the cash these tours were generating—and sheepishly released the tourist after soliciting a token confession. The Hyundai tour, formerly a carrot to get the North to engage, had become an effective stick with which to influence Pyongyang's behavior.

HELPING HANDS

Hawk engagement not only endorses such joint ventures, albeit for different reasons than those of more optimistic North Korea watchers, but it also embraces humanitarian aid—again for its own reasons rather than the standard ones. Aid groups normally view engagement as a necessary evil: one must tolerate Kim Jong Il's regime in order to help his suffering population. Hard-liners, however, look beyond the immediate effects of providing piecemeal aid to relieve short-term hardship. Hawks recognize that aid can act as investment in the will of the North Korean people to fight their regime.

Humanitarian assistance can do this in two ways. First, it can hasten the government's demise. North Korea currently faces the same dilemma regarding reform as have other illiberal regimes in the post-Cold War era. These countries need to open up in order to survive. Yet opening up can unleash forces that the government may not be able to control, and that may ultimately lead to its overthrow. Hence aid to North Korea, provided in conjunction with engagement mechanisms like the Agreed Framework, inter-Korean trade, tourism, and investment, can all help nudge the North down the slippery slope of political reform. This strategy may seem to improve the North's economic situation in the short term, but it can also create a dangerous "spiral of expectations" among the North Korean populace. And as history has shown, revolutions in repressive states generally occur not when conditions are at their worst, but once they begin to improve.

The provision of humanitarian aid can also help prepare for Korean unification by winning over the hearts and minds of Northerners. Hard-liners have traditionally held that hostility toward and isolation of the North is the most direct route toward ensuring its collapse and absorption. But this overlooks what will perhaps be the most important factor in the success of reunification: the North Korean people. The conventional wisdom is that after the repressive regime falls, North Koreans will look to Southerners as their saviors and elder siblings. This overly optimistic view, however, underestimates the degree of enmity, confusion, and distrust between the two countries, and the amount of blood they have shed fighting one another. A policy of hard-line coercion and isolation that drove Pyongyang into the ground would only make matters worse, frightening the populace and reinforcing decades of demonization by Pyongyang of Washington and Seoul.

Engagement and aid, on the other hand, convey a more compassionate image of Americans and South Koreans. As Bush stated at this February's summit in Seoul, although Washington despises Kim Jong Il's despotic regime, it has "great sympathy and empathy for the North Korean people. We want them to have food. And at the same time, we want them to have freedom." The presence of sacks of food scattered around North Korea imprinted with "United States," "Republic of Korea," and "Government of Japan" would reinforce that message. Although coercion has traditionally been more attractive to hawks, since it seems the fastest route to the North's capitulation, engagement will better prepare for the hawks' desired objective: the reunification of the Korean Peninsula.

PEACE THROUGH STRENGTH

Another way hawk engagement differs from more traditional approaches to North Korea is by being compatible with missile defense. Critics argue that the Bush administration's unswerving enthusiasm for developing and deploying ballistic-missile defense systems is wholly at odds with a policy of engaging North Korea. How, they argue, can you talk peace and prepare for war at the same time?

Such criticism ignores the fact that missile defense can actually strengthen the credibility of engagement strategies. After all, engagement is most effective when undergirded by robust defensive capabilities. This demonstrates to an adversary that the decision to engage is the choice of the strong, not the expedient of the weak—and that other, more aggressive, options exist. Progress on missile defenses would only enhance this logic by further boosting the United States' defensive power. On this point, the Armitage report was very clear: "One cannot expect North Korea to take U.S. diplomacy seriously unless we demonstrate unambiguously that the United States is prepared to bolster its ... military posture."

By pursuing both engagement and missile defense simultaneously, Washington can encourage Pyongyang's better behavior and also neutralize Kim Jong Il's one strong card: his ballistic missiles and the threat they pose to other countries in the region. Of course, questions remain as to technological feasibility and the type of defensive system that could best handle the North's missile threat while incurring the fewest negative consequences. But the larger point remains that engagement and missile defense are compatible—and complementary. Neither option is sufficient: deploying only missile defense systems would do little to solve the peninsula's tensions, whereas engagement alone would remain vulnerable to future acts of brinkmanship by Pyongyang. By pursuing missile defense, finally, the Bush administration also ensures that engagement will not be interpreted as appeasement or capitulation by critics at home or in Seoul.

The last distinct principle of hawk engagement is its insistence on the exchange of tangible compromises. This emphasis was demonstrated by Bush's inclusion of conventional force reductions on the bilateral agenda with North Korea. Although mentioned by earlier U.S. policy proposals on North Korea, the issue had never been given much attention before. By giving it much more prominence now, Bush has made clear his intent to test the seriousness of Pyongyang's supposed desire to improve relations.

Underlying the decision to put force reduction on the agenda is the hawkish belief that Pyongyang has thus far not really conceded much that it truly values. Most negotiations until now have required the North to make only potential, rather than actual, sacrifices. The missile talks at the end of the Clinton administration, for example, included a North Korean promise to give up future production, testing, and export of Taepo-Dong missiles in exchange for compensation from the United States—but would not have affected Kim Jong Il's currently deployed No-Dong missiles. Forcing Pyongyang to limit its conventional forces in exchange for engagement would truly test the regime's resolve, by targeting assets that Kim greatly values.

The emphasis on real, not hypothetical, quid pro quos can also be seen in the administration's behavior toward North Korea in the context of the new war on terror. The White House's tepid response to Pyongyang's signing of two UN antiterrorism conventions in the aftermath of September 11 offers a good example. Advocates of traditional engagement would have interpreted such moves as earnest signs of North Korea's willingness to improve ties. But hawks in the administration are holding out for more concrete and verifiable steps.

STANDING ON SHOULDERS

If hawk engagement makes such sense, why was it not employed by the Clinton administration first? The answer is not that Clinton was naive or lacked the necessary moral fortitude, as some Republicans like to argue. Proponents of engagement under Clinton understood the policy implications very well. Nonetheless, Bush, for several reasons, is in a better position than was his predecessor to wield engagement as a both a carrot and a powerful stick.

Ironically, this flexibility is largely due to the success of Clinton's engagement and South Korea's sunshine policy. These measures provided Pyongyang with new benefits (such as food, energy, and hard currency) that Bush can now implicitly threaten to withdraw. By contrast, when Clinton started making overtures to the North in 1994, there were no antecedents (in terms of tangible benefits) on which he could build or existing perks he could threaten to cut. The policy that Republicans once so vehemently criticized, in other words, has now enabled their hawkish version of engagement.

Another question is whether the Bush administration is any more ready than its predecessor was to use force against North Korea. If hawk engagement exposes the evil intentions of Pyongyang, what will follow? Bush officials, while insisting that their Korea policy is distinct from Clinton's, have so far refused to comment on what could be the greatest difference—that is, their willingness to use force if engagement fails. Given that eventuality, however, the White House would face three options.

If engagement reveals North Korea to be intractable, the most bloody and least desirable of Bush's strategies would be the actual use of force: a military campaign to coerce or terminate the regime in Pyongyang. Fighting could erupt once the North demonstrated its intention to build up its weapons despite the carrots offered, once it became clear to U.S. allies and regional powers that Washington had exhausted all avenues for cooperation, and once a coalition had been rallied for action. Responses could include preemptive military attacks, massive retaliatory strikes, the establishment of food distribution centers off North Korea's shores and borders, and guarantees of safe havens for refugees. This option implicitly assumes that early unification of the peninsula would be not a daunting cost to be avoided, but an investment in the future.

Washington's second alternative would be to face down the North with a strong show of American and allied resolve. This strategy would aim not to oust Kim Jong Il but simply to neutralize the threat posed by his weapons proliferation. Such a strategy, of course, would depend on the willingness of Pyongyang to cry uncle rather than go to war. This premise is by no means certain, however, for the North is not likely to remain passive if it decides it has nothing left to lose.

Bush's third option if Pyongyang calls his bluff would be "malign" neglect: an attempt to further isolate and contain the regime. Washington would rally Seoul, Tokyo, and other interested regional powers to push Pyongyang into a box and turn their backs on it—not relenting until Kim Jong Il gave up on his proliferation campaign. The United States and its allies would hem in North Korea militarily and intercept any vessels headed in or out of the country suspected of carrying nuclear- or missile-related material. To further weaken Pyongyang, Washington, Seoul, and Tokyo would also guarantee safe haven for refugees who made it out of the North, and would offer financial incentives to Moscow and Beijing to do the same. To ratchet up the pressure, the United States and South Korea could also reorient their military posture on the peninsula, focusing it more on long-range, deep-strike missions in the hope that this realignment would force the North into pulling back its offensive weapons so as to better defend the capital.

All three of these strategies share certain assumptions. First among them is the bet that either Pyongyang will cave in to pressure, or that Washington will have a coalition ready for coercion if it does not cave in. The second part of this wager—that the failure of a good-faith attempt to engage the North will make it easy for Washington to assemble a coalition—is plausible. The first, however, is less so. The Clinton administration seemed far more worried about it than the Bush team is, which raises the question of whether the current administration's assessment of North Korea is based on credible evidence—or merely wishful thinking.

FAST FORWARD

If the Bush administration is indeed set on pursuing hawk engagement, a number of implications follow. First, Washington will try to speed up the engagement process. Of course, this means getting Pyongyang to agree on an agenda for engagement, and that may not be easy. North Korea has already rejected several U.S. offers to resume talks, complaining that Washington is trying to unilaterally set the agenda and arguing that the United States should compensate it for the slow implementation of the Agreed Framework. Once negotiations do begin, however, the Americans can be expected to push for shorter timelines. Hawk engagement is more impatient than standard models. President Bush underscored this point in his state of the union speech, when he warned, "Time is not on our side. I will not wait on events while dangers gather. I will not stand by as perils draw closer and closer."

Standard engagement reasons that, with greater interaction, North Korea will slowly begin to open up and reform—and that Washington should therefore wait patiently for these changes to occur. Hawks, however, have much less faith in this outcome, and see engagement largely as an instrument for revealing Pyongyang's unreconstructed intentions. Given this lack of faith, ousting the communist regime before it can build up its arsenal further starts to seem like a much more urgent priority.

Washington can also be expected to have a low tolerance for Pyongyang's brinkmanship. This may be the biggest difference between hawk engagement and standard models in the short term. If the North decides to embark on a new round of belligerence, the United States may well choose to punish it. Standard models of engagement emphasize the importance of showing great patience for the target state and constantly sending it positive signals. This administration, however, is less likely to give Pyongyang the benefit of the doubt if it starts to misbehave.

If Pyongyang truly is intent on improving relations with Washington, it will have to bear the burden of proving its good faith—through concrete measures. North Korea will have to show skeptics in the administration that they were wrong to expect the worst. Here Japan and South Korea can play a valuable role, helping convince North Korea that it must move beyond smile summitry. Seoul can do so through the secret talks it conducts with Pyongyang. Tokyo can also help with measures such as technical assistance for international inspections of North Korea's suspected nuclear waste sites.

BEYOND THE PENINSULA

The final difference between hawk engagement and more traditional alternatives is that the hawkish model offers more than mere short-term policy prescriptions. Rather, it presumes a distinct view of how developments in Korea could best suit American interests, both toward reunification and beyond. Hawk engagement not only foresees reunification but accepts that it may pose real problems for the maintenance of America's long-term power and position in the region. A united Korea might be inhospitable to a continued U.S. military presence, might result in growing Chinese influence over the peninsula, and could lead to the political isolation of Japan in the region. Hawk engagement seeks to complement current Korea policy, therefore, with other policies designed to promote a more America-friendly post-unification environment. It is crucial, hawks believe, to promote stronger relations between the two main U.S. Asian allies, Japan and South Korea, and to consolidate the trilateral Washington-Tokyo-Seoul relationship.

To accomplish this goal, four tasks are necessary. The first is to use current tensions with North Korea to build security cooperation between Japan and South Korea. Throughout the 1990s, the threat of North Korean implosion or aggression drove the unprecedented security cooperation between the two nations, involving cabinet-level bilateral meetings, search-and-rescue exercises, port calls, noncombatant evacuation operations, and academic military exchanges—all despite the deep historical mistrust between Seoul and Tokyo. These formerly taboo activities (past South Korean presidents vowed never to engage in security cooperation with their one-time colonizer, Japan, even during the Cold War and despite the North Korean threat) built confidence and created an entirely new dimension to Seoul-Tokyo relations beyond political and economic ties.

The second task is to infuse the U.S.-Japan and U.S.-South Korea alliances with a meaning and identity larger than the Cold War. History shows that the most resilient alliances are those that share a common ideology that runs deeper than the shared external threats that brought the alliance into existence. Washington must therefore deepen its alliance with South Korea and Japan, moving it beyond its narrow anti-North Korea basis. Already the allies have started talking about "maintaining regional stability" as their broader purpose—but they can do better than that. A host of other shared values can be drawn on (such as common preferences for liberal democracy, open economic markets, nonproliferation, universal human rights, antiterrorism, and peacekeeping). Grounding the alliance on ideals, not just an outside threat, would not only give the relationships some permanence but would also prevent the alignments from being washed away by shifting geostrategic currents.

Washington's third long-term task is to somehow consolidate the trilateral U.S.-Japan-South Korea alliance as a way to reaffirm the U.S. presence in the region—without offering any unconditional security guarantees. The United States has always been the strongest advocate of better Japan-South Korea relations, but the likelihood of Seoul and Tokyo's responding positively to these American burden-sharing entreaties has been highest, counterintuitively, when Washington has been perceived as less interested in underwriting the region's security. The U.S. position in Asia should therefore be reduced enough to nudge the allies toward consolidating their relationship—but not reduced so much that Japan and South Korea choose self-help solutions outside the alliance framework. What this probably means in practice is a greatly reduced American troop presence but a maintenance of the nuclear umbrella over the region.

Washington's fourth task is to consolidate the trilateral alliance without irking China. Efforts at trilateral cooperation should be as low-profile and transparent to Beijing as possible. Seoul-Tokyo security cooperation, for example, should focus not on military assets, but rather on transport platforms (for preplanned disaster relief, for example). The United States, meanwhile, could also shift its military presence in the area to one based primarily on air and sea power, with less pre-positioning of materiel and fewer ground forces south of the 38th parallel.

ENDGAME

The North Korean regime under Kim Jong Il is despicable. Pyongyang starves its people, maintains gulags nightmarish even by Stalinist standards, and generally violates almost every value the United States and the free world claim to uphold. Given the war against terrorism, however, trying to topple Kim's regime directly would run counter to American interests. The attempt would distract the United States from its missions elsewhere, further complicate already fragile relations with China and Russia, and possibly suck the U.S. armed forces into another bloody quagmire.

But this does not mean that continuing the sunshine policy of engagement as practiced by the Kim Dae Jung and Clinton administrations is necessarily the best course to take. For all its apparent maladroitness, the Bush administration is groping toward a new version of engagement that might work better than its predecessor. This strategy would not use engagement without an exit strategy, but rather as an exit strategy. If the administration can articulate and implement its approach more coherently, it might just find that, over time, its critics will come to agree.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions