Northeast Asia is in transition. After 60 years of U.S. domination, the balance of power in the region is shifting. The United States is in relative decline, China is on the ascent, and Japan and South Korea are in flux. The implications for Washington are profound: Northeast Asia is home to three of the world's 11 largest economies and three of its four largest standing armies.

For the past half century, the United States has relied almost exclusively on bilateral alliances to promote its interests in the area. But these are now under assault and will no longer provide a sufficient foundation for U.S. policy in the future. The forces driving the region's transformation are complex and include economic, security, demographic, and nationalist components. To maximize its influence going forward, Washington must acknowledge that the transition is inevitable, identify the trends shaping it, and embrace new tools and regimes that broaden the base the United States relies on to project power. With so many variables at play simultaneously, this will not be an easy task. The next five to ten years are critical. They will set the stage for the next half century or longer.

TRADING PLACES

The United States has dominated Northeast Asia economically since the end of World War II, gaining support for its policies there with trade and aid. Today, however, the United States is no longer as powerful; it now shares the stage with China.

In 2007, China's trade with Japan, the world's second-largest economy, surpassed U.S. trade with Japan for the first time since World War II. Similarly, in 2004 China replaced the United States as South Korea's largest trading partner. (In 1991, one year before it normalized relations with South Korea, China accounted for just over one percent of South Korea's exports, compared with 26 percent for the United States. By 2006, China accounted for almost 22 percent and the United States for just 15 percent.) Even if the recently negotiated U.S.-South Korean free-trade agreement is ratified, it will not return the United States to the top spot.

This decline in U.S. economic influence does not reflect a decline in actual trade between the United States and its Northeast Asian partners; that has grown impressively in absolute numbers. Rather, it is a decline relative to China's economic resurgence. Adjusted for purchasing-power parity, China's share of global GDP has grown from less than five percent in 1980 to approximately 16 percent today; by this measure, China ranks second only to the United States. Similarly, China's exports have surged from just over $150 billion in 1996 to almost $1 trillion in 2006, a five-and-a-half-fold increase.

To be sure, China's economic growth has some qualifiers attached to it. China needs to achieve an annual growth rate of about seven percent just to create enough jobs for the people entering its work force each year. Failure to grow at this pace would lead to increased joblessness and possibly domestic turmoil. China's growing stature as a trading power must also be qualified. As a recent Council on Foreign Relations task-force report on U.S.-Chinese relations noted, approximately 65 percent of the value of China's exports to the United States is accounted for by the raw materials, parts, and goods that China imports from other Asian nations.

Notwithstanding these factors, China's economic rise has altered the balance of power in Northeast Asia, with both negative and positive implications. From the United States' perspective, China's ascendance is a double-edged sword. On the positive side, U.S.-Chinese trade grew from $64 billion in 1996 to $343 billion in 2006, and U.S. GDP is 0.6 percent higher today than it otherwise would be as a result of trade and investment with China since 2001. In the past decade, U.S. exports to China have increased from just $12 billion to almost $55 billion—an amount that exceeds U.S. exports to Argentina, France, Italy, Russia, and Spain combined. In fact, China is the fourth-largest market for U.S. exports and this year could surpass Japan as the third-largest. Finally, China has become the largest source of U.S. imports. Although the trade gap between the two countries (which amounted to $233 billion in 2006) is a major concern in Washington, cheap goods from China have helped keep a lid on prices for U.S. consumers.

On the negative side, China's economic ascendance means that an important lever of U.S. influence in Northeast Asia has been greatly weakened. This is particularly true given South Korea's simultaneous and equally dramatic economic rise. Washington can no longer rely on its economic muscle to persuade Seoul to embrace U.S. policies. Beyond being the 11th-largest economy in the world and a major holder of U.S. debt, South Korea now trades more with China than with the United States. As a result, South Korea is less dependent on Washington today than at any time since the end of the Korean War, particularly given its increased military capability (which is directly tied to its economic standing and ability to buy weapons). This, in turn, has increased Seoul's geopolitical options in the region. In recent years, the South Korean government has demonstrated this newfound strength by vehemently opposing the hard-line approach toward North Korea advocated by the Bush administration.

Another potential downside for the United States arises from the fact that as the amount of U.S. debt held outside the United States has surged, China, Japan, and South Korea have accumulated the lion's share of it. As of March 2007, Japan and China (excluding Hong Kong) ranked first and second, respectively, as the world's largest foreign holders of U.S. debt, together accounting for 47 percent of the almost $2.2 trillion total. China, in particular, has been a major player recently, increasing its share by almost $100 billion in the year ending March 31, 2007. The implications are potentially far-reaching. If China simply stops buying U.S. Treasury bills at the same pace as it has been, it could damage the U.S. economy. That means Beijing has leverage over the United States that it could employ in the area, possibly with respect to Taiwan.

Finally, the new economic dynamic in Northeast Asia has had an impact on Japan. Lacking a strong military since the end of World War II, Japan has relied on its economic might to shape and protect its security interests. But China's recent resurgence has diminished Japan's economic stature in Northeast Asia compared with what it was in the 1970s and 1980s. Furthermore, Tokyo has cut the amount of global development aid it distributes, much of it in Asia, by 35 percent since 1997, in large part because of economic troubles. Unable to use its economic muscle as effectively as it did in the past, Japan is resorting to a new form of nationalism as a way to shape and protect its security interests. The full impact of this change is still unknown.

To be sure, the shifting economic picture in Northeast Asia also has some clear positive effects. The most important is that greater economic integration among China, Japan, and South Korea decreases the likelihood of confrontation between them for one simple reason: all sides simply have too much at stake economically to risk upsetting the status quo. This is also true of U.S. relations with Northeast Asia: the region now accounts for 25 percent of global trade and 24 percent of U.S. trade, giving the United States a major stake in stability there.

A REVOLUTION IN MILITARY AFFAIRS

The new economic dynamic in Northeast Asia is only one factor changing the region's balance of power. The rapid rebalancing of military forces has also been a critical ingredient, with important realignments under way in Japan, South Korea, and China.

The U.S.-Japanese relationship continues to be the most important alliance in Northeast Asia and should remain a pillar of the United States' presence in the region. Nevertheless, Japan is fundamentally reassessing how it views its own security needs and is rapidly adopting a more assertive posture in the face of China's economic and military ascendance and the possible reunification of North and South Korea. It also recognizes that as the world's second-largest economy it must participate more actively in global security, particularly if it wants to win a permanent seat on the UN Security Council.

The most publicized security-related change in Japan is the drop in the number of U.S. troops stationed in the country. Washington and Tokyo have agreed that 8,000 U.S. marines positioned on Okinawa will be redeployed to Guam, leaving a total of 40,000-42,000 U.S. troops in Japan. This change, although emotionally important to the Japanese, is unlikely to affect the operational capability of U.S. forces in the Pacific. Advances in military technology allow the United States to do more with fewer troops stationed farther from the battlefield. Starting in 2008, the United States will also base a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier in Japan for the first time, bringing a new feature to its posture there. Joint military exercises between U.S. and Japanese forces have further improved integration and interoperability between the two forces, two features that were notoriously poor in the past. Finally, although Japan's defense force remains relatively small, with 240,000 troops, its $44 billion budget is the world's fifth-largest. The Japanese Self-Defense Forces are also well equipped, with 1,000 tanks, a blue-water navy, and an air force that is scheduled to accept delivery this year of midair refueling tankers, an addition that will extend Japan's operational reach beyond self-defense.

The more profound changes in Japan's security posture, however, have been in the realm of policy and institutional reform. Constrained by a U.S.-written pacifist constitution, Japan watched the Cold War from the sidelines and left its security in the hands of the United States while it concentrated on its economic development. As the historian Kenneth Pyle notes in his book Japan Rising, during that era Tokyo imposed on itself eight security-related restraints. It vowed not to deploy Japanese troops overseas, participate in collective self-defense arrangements, develop power-projection capabilities for its military, develop nuclear weapons, export arms, share defense-related technology, spend more than one percent of its GDP on defense, or use outer space for military purposes.

Today, as Pyle notes, Tokyo is scaling back or abandoning all of these self-imposed restraints. In addition to supplying fuel for the warships of the coalition forces operating in Afghanistan, this past May, the Diet passed a bill calling for a national referendum as early as 2010 to amend Article 9 of the constitution, which renounces war, prohibits the threat or use of force to settle international disputes, and bans Japan from having a formal military. The government has also been seeking to reinterpret the constitution in order to allow Japan to engage in collective self-defense with the United States, which could theoretically include supporting the United States in a conflict with China over Taiwan. Japan is seeking to develop its capability to project power: earlier this year, it requested to buy 50 F-22 fighter bombers from the United States, it has purchased the midair refueling tankers, and in August it launched the Hyuga, an aircraft carrier for helicopters. Its decision to join the United States in developing a ballistic missile defense system for the region belies its past commitments not to export arms or share military technology. And last year, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party voted to allow Japan to use outer space for military purposes. (The Diet is expected to vote on the matter later this year.) Finally, earlier this year, Tokyo formally elevated the Japan Defense Agency to the status of a full ministry. The move's symbolism was not lost on observers: on security matters, Tokyo is coming out of its shell.

Even the two remaining restraints on Japan's military power—the one-percent-of-GDP cap on defense spending and the prohibition on developing nuclear arms—are on shaky ground. Tokyo has managed to stay under the spending cap by sleights of hand in how it reports its defense budget. And although Tokyo has had no plans to develop a nuclear weapon, it could do so quickly. A deterioration of the situation in North Korea could provide Japan with the rationale to join the nuclear club, a move that would be directed as much toward China as toward the Korean Peninsula.

Like Japan, South Korea is undergoing a fundamental realignment of its security relationship with the United States—a transformation that has occurred at the same time as the two countries' alliance has become strained over diplomatic issues such as how to handle North Korea. As it did with its force in Japan, Washington is downsizing the U.S. force stationed in South Korea. Current estimates are for a drop from 39,000 in the 1990s to 25,000 troops by the end of 2008. Much of this drawdown has already occurred, and most U.S. troops have been redeployed from the demilitarized zone. Seoul and Washington have further agreed to move the U.S. force's headquarters from Seoul to bases south of the Han River, freeing up valuable land in the heart of the capital, which has seen property prices skyrocket in the past 20 years. When the relocation is complete, a total of 59 U.S. military facilities covering 38,000 acres—two-thirds of the land granted to the U.S. military under the existing Status of Forces Agreement—will have been handed back to South Korea. More important still is the joint decision to dismantle the current Combined Forces Command by April 2012, which will result in the United States' handing over wartime operational control of South Korean troops on the peninsula to Seoul. It is hoped that these moves will help tamp down rising anti-Americanism in South Korea, which has been palpable in recent years.

Despite this significant realignment of U.S. forces in South Korea, the first since the end of the Korean War, the United States' ability to project military power on the peninsula is unlikely to decrease. Technological advancements and strong interoperability mean that the United States and South Korea will be able to defend against an attack by North Korea with fewer U.S. troops stationed farther from the demilitarized zone. Furthermore, South Korea has a well-trained, highly disciplined, and well-equipped military of 700,000 troops. And the South Korean Ministry of National Defense has requested an average defense-budget increase of 11 percent per year until 2015 and nine percent from 2015 to 2020.

Notwithstanding the major shifts occurring in Japan and South Korea, the most significant change in the region's security structure is China's extensive military modernization. China is fundamentally transforming its military from a force designed to fight massive wars of attrition to a more modern, leaner force better suited to fighting shorter high-intensity wars. To this end, Beijing has downsized it from 4.2 million members in 1987 to 2.3 million today—still more than twice the number of all Japanese, South Korean, and U.S. troops in the region. The Chinese military is also modernizing its equipment, principally with a view to a potential conflict with Taiwan but possibly to project force farther afield. Although it is still building a blue-water navy, China already boasts 72 destroyers and frigates, 50 medium-weight and heavy amphibious lift ships, 41 coastal missile patrol craft, five nuclear ballistic missile and attack submarines, and 53 diesel-electric attack submarines, many of which are considered to be the most silent in the world. (In October last year, a Chinese-built Song-class diesel-electric submarine tracked a U.S. battle group in the Pacific undetected until it surfaced within firing range of the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Kitty Hawk.) The Chinese air force has also been upgrading its equipment. The fleet now includes SU-30 advanced fighter bombers acquired from Russia, a version of the SU-27 it is developing under a coproduction deal with Moscow, and its premier fighter, the Chinese-produced fourth-generation F-10 aircraft. It also possesses midair refueling tankers that extend its reach throughout the region and beyond.

The biggest change in China's military posture concerns its missile capability. The Chinese armed forces have approximately 1,000 short-, medium-, and intermediate-range ballistic missiles and between 36 and 44 intercontinental ballistic missiles. The arsenal, which is expanding by more than 100 missiles per year, is primarily aimed at Taiwan but can target Japan as well. Moreover, Beijing's use of an antisatellite missile this past January to shoot down an old weather satellite in low orbit announced China's entry into the age of space warfare and its potential ability to disrupt satellites critical to U.S. military operations in Asia.

China's military modernization has not come cheap. Beijing has reported that it will spend $45 billion on defense this year, an increase of almost 18 percent from last year and the 19th consecutive double-digit percentage increase of China's annual defense budget. The U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency estimates that China's actual military spending could be as high as $125 billion, almost three times the official number.

The rise of China's military power, coupled with the transformations under way in Japan and South Korea, presents critical challenges for Washington. Although the United States remains the dominant military power in Northeast Asia—China still lags far behind—it is clearly no longer the only player. China can now affect U.S. operations in the Taiwan Strait in a way that it could not as recently as 1996. That year, defying Beijing's protests, the United States sent two carrier groups off the coast of Taiwan after China conducted a series of missile tests in waters within 35 miles of two major Taiwanese ports. Today, a U.S. response of this nature would be far more problematic—and perhaps less likely.

On the other hand, the emerging security situation in Northeast Asia presents opportunities for cooperation. The U.S.-Japanese alliance is stronger than it has been in many years in part because Japan, faced with China's military modernization, is looking to strengthen its security ties with the United States as a countermeasure. The U.S.-South Korean security bond has also been reaffirmed, albeit on different terms. Seoul understands the need for U.S. troops to remain engaged in the region—not only to assist in the event of a confrontation with North Korea but also as a hedge against China's ascendance. And once the new foundations of the U.S.-Japanese and U.S.-South Korean relationships are in place, they are unlikely to change for the next several decades.

If anything, it is Washington that must demonstrate its intention to stay fully engaged in the region. Downsizing U.S. forces could create the perception that the United States is a wounded giant stretched so thin by its commitments elsewhere that it is failing to pay sufficient attention to the Pacific. Indeed, U.S. military leaders in the region emphatically voice this concern to anyone who will listen.

GROUNDSWELL OF NATIONALISM

Economic and security matters are not the only factors affecting the balance of power in Northeast Asia. Changing demographics and rising nationalism also are.

The demographic changes in Japan are the most pronounced. Japan's population peaked last year at close to 128 million. The number of Japanese males is expected to decline from 62 million today to approximately 47 million in 2050, with fewer than 10 million between the ages of 20 and 40 by then. Unless it turns to conscription, Japan will find it difficult to field a military even the size of its force today—already the smallest among the major powers in Northeast Asia. Notwithstanding the purchase of advanced military hardware, this reality could limit Tokyo's role in the region. Additionally, as Japan's population ages—the percentage of the population aged 65 and above is projected to grow from 21 percent today to 36 percent in 2050—the country will have to expend considerable resources on caring for its elderly. This focus on domestic concerns could limit Tokyo's foreign policy agenda and regional ambitions.

In South Korea, it is a bulging younger generation that is changing the landscape. Eighty-three percent of South Korea's population today was born after the end of the Korean War, and 50 percent of it is 30 years old or younger. Whereas older generations of South Koreans remember the United States' role in the Korean War, the 30-and-under group does not. It views the United States as much as a bully as a friend and North Korea more as a cousin than an enemy.

China faces demographic challenges of a different nature. Its population, already 1.32 billion today, is not expected to peak until approximately 2030, which means that its economy must grow fast enough to absorb its expanding population. Absent a crisis, Beijing is not likely to act assertively in external affairs until it is confident that the country is on solid ground domestically. This turning point in China could come at the very same time that Japan's demographic trends cause Tokyo to focus inward—and that could prove to be a tense period for Northeast Asia.

The demographic changes affecting the region's major players are coinciding with the rise of three forms of nationalism. The first, anti-Americanism, is particularly prevalent in China. According to a Pew Research Center poll released last June, only 34 percent of the Chinese surveyed said they held a positive view of the United States. The number of Japanese with a favorable view was higher but dropping: 61 percent, down from 77 percent in 2000. In South Korea, favorable views of the United States dropped as low as 35 percent, according to a BBC poll released in January, before improving to 58 percent, according to the June Pew poll, following progress in trade negotiations between the United States and South Korea and a narrowing of differences between the two countries over how to engage North Korea.

A second, more worrisome form of nationalism is the dislike that the major players in the region have for one another. According to an earlier Pew poll released last year, about 70 percent of the Japanese respondents viewed China unfavorably and thought it was an arrogant power, and 90 percent saw China's growing military power as a bad development. About 70 percent of the Chinese respondents, for their part, viewed Japan unfavorably and thought it was nationalist and arrogant. There is some positive news, however. Only 33 percent of the Chinese and Japanese respondents viewed the other group as an adversary, and both groups viewed South Koreans more positively than they viewed each other, with 64 percent of the Chinese and 56 percent of the Japanese surveyed holding a favorable impression of their neighbor.

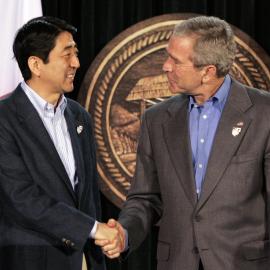

The third form of nationalism is of a more traditional character. China, Japan, and South Korea are fiercely proud nations with long histories, and as their power grows, they are demanding the respect that befits their status. In South Korea, this nationalism is reflected in the government's decision to engage North Korea regardless of U.S. or Japanese opposition—a decision driven in part by the deep sense of national identity that South Koreans share with their brethren to the north. In Japan, nationalism was visible in former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's refusal to fully acknowledge the part that the Japanese army played in coercing women into brothels during World War II and in Tokyo's recent decision to revise the country's textbooks to downplay Japan's role in the war. Abe's successor will likely be less outwardly right wing, but nationalism will continue to be an important factor in shaping Japan's domestic and foreign policies. In China, nationalism primarily manifests itself in Beijing's insistence that Taiwan not take any steps toward independence and in Beijing's seeming willingness to go to war over the issue. It was also on prominent display in 2005, when large riots erupted across China in response to Tokyo's efforts to secure a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, a move that would dilute China's proud status as the only Asian nation to hold one.

POWER TOOLS

Since the end of World War II, U.S. policy in Northeast Asia has been primarily based on bilateral alliances throughout the region, most prominently with Japan and South Korea. Counterintuitively perhaps, until recently China endorsed this approach. It relied on Washington to keep Japan's ambitions in check by providing for its security and to maintain stability on the Korean Peninsula by acting as a deterrent.

But today, China is no longer willing to leave the region's stability in Washington's hands and is working to counter U.S. alliances. Beijing has conducted a diplomatic offensive to build up its own bilateral relationships in the area. Over the past two decades, it has established diplomatic relations with longtime U.S. allies such as Singapore and South Korea, reestablished relations with Indonesia, and mended fences with India, Russia, and Vietnam. It is also beginning to improve its relations with Japan. Although tensions between the two countries remain high, reciprocal state visits over the past year have helped ease them.

China is also reaching out in the multilateral arena. Having overcome its distrust of multilateral forums (which arose in part from its fear of always being outvoted), China now participates in them more fully than Washington. Beijing is a member of ASEAN + 1 (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and China), ASEAN + 3 (ASEAN and China, Japan, and South Korea), the ASEAN Regional Forum, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the East Asian Summit. China is also building a network of free-trade agreements in Asia to supplement its bilateral and multilateral relationships. In addition to the Chinese-ASEAN free-trade agreement, it has a free-trade agreement with Thailand, is negotiating or conducting feasibility studies for trade deals with Australia and India, and has proposed an ASEAN + 3 free-trade area.

It is imperative that as the balance of power in Northeast Asia shifts, the United States develop a comprehensive, coherent, and consistent set of policies that address the economic, security, demographic, and nationalist components underpinning the transition while taking into account China's diplomatic initiatives. The United States has an extensive set of tools designed to serve this end, including bilateral alliances, multilateral forums, and free-trade agreements. But it does not use all of them to the extent that it should. The tool kit is also missing critical components, particularly relating to security regimes and soft-power initiatives. The United States should fill these gaps immediately and use all available instruments in various combinations, favoring neither bilateralism over multilateralism, as it has in the past, nor multilateralism over bilateralism.

For example, the United States should more fully embrace the ASEAN Regional Forum and APEC and negotiate more bilateral and multilateral free-trade agreements, particularly with India and ASEAN. It should also join the East Asian Summit, even though the group's mandate overlaps somewhat with that of the broader but more unwieldy APEC, and seek observer status in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Furthermore, the United States should more frequently employ its hard power for soft-power purposes, as it did in 2005, when it dispatched the U.S.N.S. Mercy on a humanitarian mission to Indonesia after it was devastated by a tsunami. Equipped with 12 operating rooms and 1,000 hospital beds, the Mercy's crew treated almost 10,000 patients and performed close to 20,000 medical procedures. The goodwill the mission generated was quantifiable: according to the Pew Research Center, in 2003 only 15 percent of Indonesians polled reported having a favorable view of the United States, but by 2005, after the Mercy's post-tsunami deployment, that number had jumped to 38 percent. Washington wisely undertook a similar goodwill effort in 2006 by sending the Mercy into South and Southeast Asia. Over the course of five months, its crew treated almost 200,000 patients, performed more than 1,000 surgeries, and trained more than 6,000 local medical professionals. A small team of sailors from the U.S. Naval Construction Force also made repairs or improvements to medical centers, schools, and other infrastructure onshore. Soft-power initiatives such as these could help counter anti-Americanism, especially at a time when the war in Iraq has left many nations with the impression that the United States uses its military might inappropriately.

In addition to more fully utilizing some of the tools it already has, the United States should also immediately add some that it is missing, particularly in the security realm. For example, a security regime for Northeast Asia is urgently needed. The recent six-party nuclear agreement involving North Korea could serve as a catalyst for a much-needed Northeast Asian security forum, which could initially comprise the signatories to the agreement: China, Japan, North Korea, Russia, South Korea, and the United States. To ensure that North Korea does not hold these meetings hostage while still encouraging its participation, the forum should assume a "5 + 1" format, in which North Korea would be an official observer. This status would allow North Korea to participate if it pleased but not prohibit the group from meeting if it did not. The forum, which need not preclude more six-party talks on the narrower issue of North Korea's nuclear program, could address issues such as arms control, crisis management, and conflict prevention and resolution. It could further serve as a valuable mechanism for managing tensions between China, Japan, and South Korea. From Washington's perspective, such a forum would also allow the United States to reassert its leadership in a way that is not possible in larger security groupings such as the ASEAN Regional Forum.

Another important tool that the United States should add is a meaningful security relationship with China. Creating such a bilateral arrangement would require striking a fine balance. On the one hand, China should not be allowed to see so much of the United States' military strength that it knows exactly how to benchmark it against its own military. On the other, it is important to build solid military-to-military relationships, particularly at the level of midranking officers. Until last year, the United States and China had never held joint military exercises, even though China had held such exercises with at least ten other nations, including India. (This past May, Beijing agreed to hold further periodic joint exercises with New Delhi partly because it is concerned that the United States will try to contain China by embracing India.) Going forward, Washington should carefully observe China's expanding military ties with other nations and take proactive steps to strengthen its own military ties with Beijing.

PICKING UP THE PACE

Today, a dangerous dynamic is emerging in Northeast Asia. Three powerful, nationalist states with a history of hostility between them are simultaneously awakening from a period of quiescence and jockeying for power. For the past half century, the United States has assumed that its bilateral ties with Japan and South Korea were defining relationships on which it could build the entire architecture for its policies in Northeast Asia. In part because of these ties, it further assumed that it could largely set the agenda with China.

Both assumptions are no longer valid, even though the United States continues to exercise enormous influence in the region. Although U.S. ties with Japan and South Korea should be maintained and, where possible, strengthened, they will no longer provide a sufficient foundation for the United States' power in Northeast Asia on their own. China, meanwhile, has skillfully brought itself to the point where it can largely chart its own course.

Maintaining stability in the region is critical. If the transformation now under way spins out of control, it could threaten fundamental U.S. interests. As the United States develops a new strategy for Northeast Asia, it must find common ground and shared interests with the region's major players. To maximize its influence, it should embrace a broad platform of initiatives, including bilateral alliances, multilateral forums, free-trade agreements, and soft-power projects that build goodwill, and use all of these tools in various combinations depending on the issue and the players involved. In this respect, Washington is behind the curve—and behind China. If it does not move quickly, it will find its stature in Northeast Asia greatly diminished at precisely the time when the region takes its place at the center of the world stage.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions