The rapid economic development of Asia since World War II -- starting with Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, then extending to Hong Kong and Singapore, and finally taking hold powerfully in India and mainland China -- has forever altered the global balance of power. These countries recognize the importance of an educated work force to economic growth, and they understand that investing in research makes their economies more innovative and competitive. Beginning in the 1960s, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan sought to provide their populations with greater access to postsecondary education, and they achieved impressive results.

Today, China and India have an even more ambitious agenda. Both seek to expand their higher-education systems, and since the late 1990s, China has done so dramatically. They are also aspiring to create a limited number of world-class universities. In China, the nine universities that receive the most supplemental government funding recently self-identified as the C9 -- China's Ivy League. In India, the Ministry of Human Resource Development recently announced its intention to build 14 new comprehensive universities of "world-class" stature. Other Asian powers are eager not to be left behind: Singapore is planning a new public university of technology and design, in addition to a new American-style liberal arts college affiliated with the National University.

Such initiatives suggest that governments in Asia understand that overhauling their higher-education systems is required to sustain economic growth in a postindustrial, knowledge-based global economy. They are making progress by investing in research, reforming traditional approaches to curricula and pedagogy, and beginning to attract outstanding faculty from abroad. Many challenges remain, but it is more likely than not that by midcentury the top Asian universities will stand among the best universities in the world.

THE PIONEERS

In the early stages of their countries' postwar development, Asian governments understood that greater access to higher education would be a prerequisite to sustained economic growth. A literate, well-trained labor force helped transform Japan and South Korea over the course of the past half century, first from agricultural to manufacturing economies, then from economies focused on low-skilled manufacturing to those focused on high-skilled manufacturing. With substantial government investment, the higher-education systems in both countries expanded rapidly. In Japan, the gross enrollment ratio -- the fraction of the university-age population that is actually enrolled in some type of postsecondary educational institution -- rose from nine percent in 1960 to 42 percent by the mid-1990s. In South Korea, the increase was even more dramatic, from five percent in 1960 to just over 50 percent in the mid-1990s.

During this period, China and India lagged far behind. Even in the mid-1990s, only five percent of university-age Chinese citizens remained in school, putting China on par with Bangladesh, Botswana, and Swaziland. In India, despite a postwar effort to create a group of national comprehensive universities and, later, the elite Indian Institutes of Technology, the gross enrollment rate remained a mere seven percent in the 1990s.

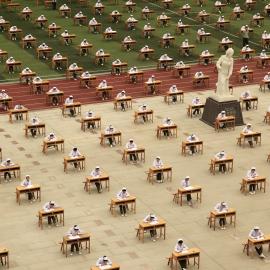

The results of Beijing's investment have been staggering. Over the decade following Jiang's declaration, the number of institutions of higher education in China more than doubled, from 1,022 to 2,263. Meanwhile, the number of Chinese who enroll in a university each year has quintupled -- rising from one million students in 1997 to more than 5.5 million in 2007. This expansion is without precedent, and university enrollment in China is now the largest in the world.

China still has a long way to go to achieve its aspirations concerning access to higher education. Despite the enormous surge, China's gross enrollment rate for higher education stands at 23 percent, compared with 58 percent in Japan, 59 percent in the United Kingdom, and 82 percent in the United States. And the expansion has slowed since 2006, driven by concerns that enrollments have outstripped the capacity of faculty to maintain quality in some institutions. The student-teacher ratio has roughly doubled over the past decade. But enrollment will continue to rise as more teachers are trained, since China's current leaders are keenly aware of the importance of a well-educated labor force for economic development.

India's achievement to date has not been nearly as impressive, but its aspirations are no less ambitious. Already the world's largest democracy, India is on track to become the most populous country in two decades, and by 2050, if its growth can be sustained, its economy could become second in size only to China's. To fuel that economic growth, India's human resource development minister, Kapil Sibal, aims to increase his country's gross enrollment ratio in postsecondary education from 12 percent to 30 percent by 2020. This goal translates to an increase of 40 million students in Indian universities over the next decade -- an ambitious target, to be sure, but even half that number would be a remarkable accomplishment.

COMPETING WITH THE BEST

Having made tremendous progress in expanding access to higher education, the leading countries of Asia are now focused on an even more challenging goal: building universities that can compete with the finest in the world. The governments of China, India, Singapore, and South Korea are explicitly seeking to elevate some of their universities to this exalted status because they recognize the important role that university-based scientific research has played in driving economic growth in the United States, western Europe, and Japan. And they understand that world-class universities are the ideal place to educate students for careers in science, industry, government, and civil society -- creating people who have the intellectual breadth and critical-thinking skills to solve problems, to innovate, and to lead.

To oversimplify, consider the following puzzle: Japan grew much more rapidly than the United States from 1950 to 1990, as its surplus labor was absorbed into industry, and much more slowly than the United States thereafter. Now consider whether Japan would have grown so slowly if Microsoft, Netscape, Apple, and Google had been Japanese companies. Probably not. It was innovation based on science that propelled the United States past Japan during the two decades prior to the crash of 2008. It was Japan's failure to innovate that caused it to lag behind.

Developing top universities is a tall order. World-class universities achieve their status by assembling scholars who are global leaders in their fields. This takes time. It took centuries for Harvard and Yale to achieve parity with Oxford and Cambridge and more than half a century for Stanford and the University of Chicago (both founded in 1892) to achieve world-class reputations. The only Asian university to have broken into the top 25 in global rankings is the University of Tokyo, which was founded in 1877.

Most of all, building universities capable of world-class research means attracting scholars of the highest quality. In the sciences, this requires first-class facilities, adequate funding, and competitive salaries and benefits. China is making substantial investments on all three fronts. Shanghai's top universities -- Fudan, Shanghai Jiao Tong, and Tongji -- have each developed whole new campuses within the past few years. They have outstanding research facilities and are located close to industrial partners. Funding for research in China has grown in parallel with the expansion of university enrollment, and Chinese universities now compete much more effectively for faculty talent worldwide. In the 1990s, only ten percent of those Chinese who received Ph.D.'s in the sciences and engineering in the United States returned home. That number is now rising, and increasingly, China has been able to repatriate midcareer scholars from tenured positions in the United States and the United Kingdom; they are attracted by the greatly improved working conditions and by the opportunity to participate in China's rise. India, too, is beginning to have more success in drawing on its diaspora, but it has yet to make the kind of investments that China has made in improving facilities, stepping up research funding, and increasing compensation for top professors.

THE RESEARCH PRIORITY

Bush's 1945 report established the framework for U.S. government support for scientific research. It was founded on three principles, which still govern today. First, the federal government bears the primary responsibility for funding basic science. Second, universities -- rather than government-run laboratories, nonteaching research institutions, or private companies -- are the primary institutions responsible for carrying out this government-funded research. Third, although the government determines the total amount of funding available for different scientific fields, specific projects and programs are assessed not on political or commercial grounds but through an intensely competitive process of peer review, in which independent experts judge proposals on their scientific merit alone.

This system has been an extraordinary success. It has the benefit of exposing postgraduate scientists-in-training -- even those who do not end up pursuing academic careers in the long run -- to the most cutting-edge techniques and areas of research. It allows undergraduates to witness meaningful science firsthand, rather than merely reading about the last decade's milestones in a textbook. And it means that the best research gets funded -- not the research proposed by the most senior members of a department's faculty or by those who are the most politically connected.

This has not been the typical scheme for facilitating research in Asia. Historically, most scientific research there has taken place apart from universities, in research institutes and government laboratories. In China, Japan, and South Korea, funding has been directed primarily toward applied research and development (R & D), with a very small share devoted to basic science. In China, for instance, only about five percent of R & D spending is aimed at basic research, compared with 10-30 percent in most developed countries. As a share of GDP, the United States spends seven times as much as China on basic research.

Moreover, peer review is barely used for grant funding in most of Asia. Japan has historically placed the bulk of its research resources in the hands of its most senior scientists. Despite Tokyo's acknowledging several years ago that a greater share of research funding should be subjected to peer review, only 14 percent of the Japanese government's spending on non-defense-related research in 2008 was subjected to competitive review, compared with 73 percent in the United States.

Yet there is no doubt that Asian governments have made R & D a priority. R & D spending in China has increased rapidly in recent years, rising from 0.6 percent of the country's GDP in 1995 to 1.3 percent in 2005. That is still well below the spending in more advanced countries, but it is likely to keep climbing. The Chinese government has set a goal of increasing R & D spending to 2.5 percent of GDP by 2020. And there is already some evidence of the payoff from increased research funding: from 1995 to 2005, for example, Chinese scholars more than quadrupled the number of articles they published in leading scientific and engineering journals. Only the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan account for more.

MORE THAN MEMORIZATION

But it takes more than research capacity alone for a nation to develop economically. It takes well-educated citizens of broad perspective and dynamic entrepreneurs capable of independent and original thinking. The leaders of China, in particular, have been very explicit in recognizing that two elements are missing from their universities: multidisciplinary breadth and the cultivation of critical thinking. Asian universities, like those in Europe but unlike those in the United States, have traditionally been highly specialized. Students pick a discipline or a profession at age 18 and study little else thereafter. And unlike in elite European and U.S. universities, pedagogy in China, Japan, and South Korea relies heavily on rote learning; students are passive listeners, and they rarely challenge one another or their professors in classes. Learning focuses on the mastery of content, not on the development of the capacity for independent and critical thinking.

The traditional Asian approaches to curricula and pedagogy may work well for training line engineers and midlevel government officials, but they are less suited to fostering leadership and innovation. While U.S. and British politicians worry that Asia, and China in particular, is training more scientists and engineers than the West, the Chinese and others in Asia are worrying that their students lack the independence and creativity necessary for their countries' long-term economic growth. They fear that specialization makes their graduates narrow and that traditional Asian pedagogy makes them unimaginative. Officials in China, Singapore, and South Korea have become increasingly attracted to the American model of undergraduate education. Universities in the United States typically provide students with two years to explore a variety of subjects before choosing a single subject on which to concentrate during their final two years. The logic behind this approach is that exposing students to multiple disciplines gives them alternative perspectives on the world, which prepares them for new and unexpected problems.

In today's knowledge economy, no less than in the nineteenth century, when the philosophy of liberal education was articulated by Cardinal John Henry Newman, it is not subject-specific knowledge but the ability to assimilate new information and solve problems that is the most important characteristic of a well-educated person. The Yale Report of 1828 -- an influential document written by Jeremiah Day (who was at the time president of Yale), one of his trustees, and a committee of faculty -- distinguished between "the discipline" and "the furniture" of the mind. Mastering a specific body of knowledge -- acquiring "the furniture" -- is of little permanent value in a rapidly changing world. Students who aspire to be leaders in business, medicine, law, government, or academia need "the discipline" of mind -- the ability to adapt to constantly changing circumstances, confront new facts, and find creative ways to solve problems.

There has already been dramatic movement toward American-style curricula in Asia. Peking University introduced the Yuanpei Honors Program in 2001, a pilot program that immerses a select group of the most gifted Chinese students in a liberal arts environment. These students live together and sample a wide variety of subjects for two years before choosing a major field of study. At Fudan University, all students now take a common, multidisciplinary curriculum during their first year before proceeding with the study of their chosen discipline or profession. At Nanjing University, students are no longer required to choose a subject when they apply for admission; they may instead choose among more than 60 general-education courses in their first year before deciding on a specialization. Yonsei University, in South Korea, has opened a liberal arts college on its campus, and the National University of Singapore has created the University Scholars Program, in which students do extensive work outside their discipline or professional specialization.

Changing the style of teaching is much more difficult than changing the curricula. It is more expensive to offer classes with smaller enrollments, and it requires the faculty to adopt new methods. This is a major challenge in China, Japan, and South Korea, where traditional Asian pedagogy prevails. (It is much less of a concern in India and Singapore, where the legacy of British influence has created a professoriate much more comfortable with engaging students interactively.) The Chinese, in particular, are eager to tackle this challenge, and they recognize that those professors who have studied abroad and been exposed to other methods of instruction are best equipped to revamp teaching. Increasing opportunities for Asian students to study in the West and for Western students to spend time in Asian universities will also help accelerate the transformation.

In China, however, gaining widespread support for such changes is difficult given the unique way in which the responsibilities of running a university are divided between each institution's president and its Communist Party secretary. Often, the two leaders work together very effectively. But there are concerns that the structure of decision-making limits a university president's ability to achieve his or her academic goals, since the appointment of senior administrators -- vice presidents and deans -- is in the hands of a school's university council, which is chaired by the party secretary rather than the president. The Chinese government appears to recognize that this structure of university governance is problematic; the issue is under review by the Ministry of Education.

A FOCUS ON FLAGSHIPS

Not every university can or needs to be world class. The experiences of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany are instructive. In the United States and the United Kingdom, higher education is a differentiated system of many types of institutions, of which the comprehensive research university is merely one. And within the group of comprehensive universities, government support for research is allocated chiefly on the basis of merit, which allows some institutions to prosper while others lag behind. In the United States, fundraising reinforces this differentiation. Success breeds success, and for the most part, the strongest institutions attract the most philanthropy. In Germany, by contrast, government policy since World War II has kept universities from maintaining their distinction. After the war, the government opened enrollment, allowed the student-faculty ratio to rise everywhere, isolated the most eminent researchers in separate institutes but otherwise distributed resources on the basis of equity rather than merit. In doing so, it destroyed the worldwide distinction Germany's best universities once held. Only recently has the government decided to focus its resources on three universities in particular, in order to make them more globally competitive.

India is the anomalous case. In the 1950s and 1960s, it focused its resources on establishing five Indian Institutes of Technology. These, and the ten more added in the past two decades, are outstanding institutions for educating engineers, but they have not become globally competitive in research. And India has made no systematic effort to raise the status of any of its 14 comprehensive national universities, which are severely underfunded.

India's current minister of human resource development is determined to create world-class comprehensive universities. But the egalitarian forces that dominate the country's robust democracy -- which allow considerations of social justice to trump meritocracy in selecting students and faculty -- threaten to constrain the prospects for excellence. To a greater degree than elsewhere in Asia, the admission of students and the hiring of faculty is regulated by quotas ("reservations") ensuring representation of the historically underprivileged classes. Moreover, political considerations seem to prevent the concentration of resources on a small number of flagship institutions. Two years ago, the government announced that it would create 30 new world-class universities, one for each of India's states -- clearly an unrealistic ambition. The number was subsequently reduced to 14, one for each state without a comprehensive university, but even this goal seems unattainable.

Given the extraordinary achievements of Indian scholars throughout the diaspora, the human capital for building world-class universities back home is surely present. But it remains to be seen whether the Indian government can tolerate the disproportionately high salaries that would be necessary to attract leading scholars from around the world. Consequently, the government is pursuing a more promising strategy that would allow the establishment of branch campuses of foreign universities and reduce the regulatory burdens on private universities.

In one respect, however, India has a powerful advantage over China, at least for now. It affords faculty the freedom to pursue their intellectual interests wherever they may lead and allows students and faculty alike to express, and thus test, their most heretical and unconventional theories -- freedoms that are an indispensible feature of any great university. It may be possible to achieve world-class stature in the sciences while constraining freedom of expression in politics, the social sciences, and the humanities. Some of the specialized Soviet academies achieved such stature in mathematics and physics during the Cold War. But no comprehensive university has ever done so.

MUTUALLY ASSURED PROGRESSION

As barriers to the flow of people, goods, and information have come down, and as the process of economic development proceeds, Asian countries have increasing access to the human, physical, and informational resources needed to create top universities. If they concentrate their growing resources on a handful of institutions, tap a worldwide pool of talent, and embrace freedom of expression and freedom of inquiry, they will succeed in building world-class universities. It will not happen overnight; it will take decades. But it may happen faster than ever before.

For the West, the rise of Asian universities should be seen as an opportunity, not a threat. Consider how Yale has benefited. One of its most distinguished geneticists, Tian Xu, and members of his team now split their time between laboratories in New Haven and laboratories at Fudan University, in Shanghai. Another distinguished Yale professor, the plant biologist Xing-Wang Deng, has a similar arrangement at Peking University. In both cases, the Chinese provide abundant space and research staff to support the efforts of Yale scientists, while collaboration with the Yale scientists upgrades the skills of young Chinese professors and graduate students. Both sides win.

The same argument can be made about the flow of students and the exchange of ideas. Globalization has underscored the importance of cross-cultural experience, and the frequency of student exchanges has multiplied. As Asia's universities improve, so do the experiences of students who participate in exchange programs. Everyone benefits from the exchange of ideas, just as everyone benefits from the free exchange of goods and services.

Finally, increasing the quality of education around the world translates into better-informed and more productive citizens everywhere. The fate of the planet depends on humanity's ability to collaborate across borders to solve society's most pressing problems -- the persistence of poverty, the prevalence of disease, the proliferation of nuclear weapons, the shortage of fresh water, and the danger of global warming. Having better-educated citizens and leaders can only help.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions