By September 2008, when General Raymond Odierno replaced General David Petraeus as the top commander of the Multi-National Force-Iraq, there was a prevalent sense among Americans that the surge of additional U.S. forces into the country in 2007 had succeeded. With violence greatly reduced, the Iraq war seemed to be over. In July 2008, U.S. President George W. Bush had announced that violence in Iraq had decreased "to its lowest level since the spring of 2004" and that a significant reason for this sustained progress was "the success of the surge."

The surge capitalized on intra-Shiite and intra-Sunni struggles to help decrease violence, which created the context for the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Iraq. With U.S. troops on pace to depart entirely by December 2011, Iraqis held successful national elections last March and, after nine months of wrangling, eventually formed a broadly inclusive government in December 2010. But Odierno -- for whom I served as chief political adviser -- understood that the surge had not eliminated the root causes of conflict in Iraq. As we realized then, the Iraqis must still develop the necessary institutions to manage competition for power and resources peacefully. Iraqi elites across the political spectrum felt that the Obama administration was focused more heavily on leaving Iraq than on supporting the country's attempt to build a democratic system of government. The withdrawal of U.S. forces from Iraq should mark an evolution in the U.S.-Iraqi relationship, not Washington's disengagement. Without continued U.S. support, there is a real danger that Iraq may not succeed in using the opening provided by the surge to strengthen its stability and achieve its democratic aspirations.

ONE LAST TRY

By the end of 2006, Iraq appeared to be teetering on the edge of civil war. Tens of thousands of Iraqis had fled their homes, and Baghdad had degenerated into armed sectarian enclaves. Insurgent groups, criminal gangs, and militias of political parties used violence to achieve their particular objectives. Neighboring countries backed them with funding, paramilitary training, and weapons, further fomenting instability. Meanwhile, back in the United States, public support for the war was waning. The prevailing U.S. strategy of attempting to transfer responsibility for security to the Iraqi security forces (ISF) seemed, in the words of U.S. Army Colonel H. R. McMaster, "a rush to failure."

The question became whether the United States would leave Iraq as quickly as possible or attempt to implement a new strategy to reduce the violence -- raising U.S. troop levels and employing different tactics. Joe Biden, who was then a U.S. senator, adamantly opposed such a troop buildup, arguing in early 2007 that "a surge of up to 30,000 American troops cannot have any positive effect except for only temporary." Yet Bush, U.S. Senator John McCain, and others believed that a troop surge could provide enough security against sectarian violence to allow for political reconciliation. They were convinced that a withdrawal of forces under such circumstances would cause an all-out civil war that could spread into neighboring countries, jeopardizing oil exports across the region. Proponents of a surge also believed that abandoning Iraq would gravely harm the global reputation of the United States, boost the morale of Islamic extremists, and crush the spirit of the U.S. military.

In a televised address in January 2007, Bush announced that the United States would implement a surge of U.S. forces "to help Iraqis carry out their campaign to put down sectarian violence." Petraeus -- who became commanding general of the Multi-National Force-Iraq in January 2007 -- and Odierno, who was his second-in-command, shared responsibility for developing the new strategy on the ground. Serving as operational commander, Odierno proposed sending U.S. troops out into Iraqi population centers to protect civilians. This marked a break from the previous U.S. approach, which had U.S. troops targeting insurgents from bases on the outskirts of Iraqi cities and then quickly withdrawing, leaving the unreliable ISF in their place. Additional U.S. forces were sent to the Sunni-dominated Anbar region -- an erstwhile stronghold of al Qaeda whose tribes were beginning to abandon the terrorist group and ally with the United States -- as well as to the outskirts of Baghdad, which insurgents sought to control in order to launch attacks into the city.

Petraeus and Odierno agreed that the essence of the struggle in Iraq was (and remains) a competition between communities for power and resources. By filling the power vacuum, the U.S. military sought to buy the time and space for the Iraqi government to move forward with national reconciliation and improve its delivery of public services. U.S. troops showed that they were willing to emerge from their bases and place the defense of the Iraqi people above all else, which sent a clear message to the Iraqi public that U.S. forces would not be defeated. Many Iraqis stopped providing passive sanctuary to armed groups and, assured that the United States would protect them from reprisal, offered intelligence that enabled U.S. troops to target insurgents more accurately. Meanwhile, the United States reached out to previously hostile tribal and factional leaders, coaxing them to turn against al Qaeda and participate in the political process.

The surge accompanied and fostered other crucial internal changes. It coincided with and benefited from tectonic shifts within the Sunni community, as the Sunni nationalist insurgency and al Qaeda began competing for dominance. Al Qaeda's efforts to impose a puritanical form of Islam angered the Sunni population, and the Sunni tribes, in a time-honored fashion, retaliated when their members were killed. At the same time, the Sunnis realized that they were losing ground to the Shiite militias and came to see Iran as a greater threat than the United States. These factors drove the Sunni tribes in Anbar to turn to the United States for support in a phenomenon known as the Sunni Awakening, which spread in similar ways to other parts of the country. When the Iraqi Shiites observed that the Sunnis were battling al Qaeda themselves and preventing insurgent attacks on the Shiite community, they became less tolerant of the Shiite death squads and militias, whose legitimacy rested on their defense of Shiites against Sunni aggression. This shift reached its climax in March 2008, when Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki felt that his government was being so undermined by the behavior of Jaish al-Mahdi, the Shiite militia led by the Iraqi cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, that he ordered military operations against it in Basra and Baghdad. The U.S.-supported operations decimated Jaish al-Mahdi, enhancing Maliki's standing and earning him the respect of Iraq's Sunnis as well. In short, the surge succeeded in changing Iraq's political environment, encouraging the Shiites and the Sunnis to bring the civil war to an end. The improvement in the security situation convinced partisans on both sides that they could achieve their political goals only by joining the political process.

SECURING THE SURGE

The unexpected drop in violence convinced many Americans that the war in Iraq had been won. The surge had undoubtedly met its stated aim of buying the time and space necessary for the Iraqi government to advance national reconciliation and, at least in theory, develop the capacity to provide adequate public services. Yet Iraq's parties did not take advantage of the opportunity to turn progress at the local level into national reconciliation. When Odierno replaced Petraeus in September 2008, the greatest threat to Iraq's stability had become the legitimacy and capability of the government, rather than insurgents. Research and opinion polls showed that as the violence dropped, jobs and public services replaced security as the number one concern, and the government was not able to meet the public's growing expectations. I advised Odierno that we needed to meet these new hopes by preserving the fragile security gains and, at the same time, ensuring that our actions did not infringe on Iraqi sovereignty.

To quicken the pace of national reconciliation, Odierno attempted to integrate the ISF, which until that time had been predominately Shiite. From my close relationship with Maliki's advisers, I understood that the government remained suspicious of the Sunni Awakening and feared that by supporting it, the United States was creating a Sunni army that would overthrow the country's Shiite leadership. We sought to allay these concerns by pressuring the Iraqi government to place Sunni Awakening soldiers on its payroll, legitimizing them as local police forces and improving the ISF's sectarian balance. U.S. troops closely trained and monitored ISF troops, reporting instances of misconduct to the Iraqi government. As the ISF became more diverse and professional, the country became more secure.

Yet the annual United Nations Security Council resolution authorizing the presence of U.S. forces in Iraq was set to expire in December 2008, raising the possibility that the United States would have to depart the country immediately or remain there illegally, both of which would have threatened the gains made by the surge. To prevent either scenario, the U.S. and Iraqi governments entered negotiations over the U.S.-Iraq Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), which would define the future of U.S. engagement in the country.

Iraqi officials bargained tenaciously during the SOFA negotiations and extracted significant concessions from the United States. They insisted on and won greater control over the actions of U.S. forces and secured a promise of their departure from population centers by the end of June 2009 and their total withdrawal by the end of 2011. The Bush administration even allowed Iraq the "primary right to exercise jurisdiction" over U.S. military members who committed "grave premeditated felonies," such as rape, and agreed that all suspects arrested by U.S. troops would be detained under warrant and held in Iraqi facilities. To the Iraqis, this meant that U.S. forces would be operating under the rule of law rather than the rule of war, as they had been since 2003.

The U.S. military reacted apprehensively to these demands, uncomfortable with the idea of U.S. soldiers falling under foreign legal authority and worried that the announcement of concrete dates for the troop withdrawals would boost insurgent morale. Some Iraqis expressed discomfort with the deal, too. For some of them, the idea of a security agreement permitting continued foreign occupation recalled the bitter memory of a century of colonial intervention in the country's affairs. The political elites, for their part, feared that Maliki was becoming increasingly authoritarian and was consolidating his power through higher oil revenues and the ISF's growing capacity. They suspected that the SOFA would bring U.S. forces under Maliki's control, preventing the United States from playing a brokering role or guarding against sectarian and undemocratic behavior.

As expected, politicians allied with Sadr voted against the agreement in the Iraqi parliament. Some Sunni leaders also opposed the SOFA, afraid that a U.S. pullout would increase Iran's influence over Iraq and expose the Sunni community to further attacks from Shiite elements in the ISF. Despite doubts among both the U.S. military and Iraqi factions, Iraq's parliament reached a consensus to sign the agreement once its various parties felt they had achieved three important conditions: passing a resolution that demanded political reform, securing a commitment to hold a national referendum on the SOFA in July 2009, and receiving letters of assurance from the United States that repeated Washington's commitment to protect the democratic process. Meanwhile, Maliki boosted his reputation by taking a hard line in the negotiations, establishing U.S. forces as guests of the Iraqi government rather than occupiers under a UN resolution.

The SOFA was signed along with a strategic framework agreement, which provided a possible glimpse of the future of U.S.-Iraqi ties. It affirmed "the genuine desire of [Iraq and the United States] to establish a long-term relationship of cooperation and friendship" across a range of areas, including culture, health, trade, energy, communications, security, and diplomacy. Together with the SOFA, the Strategic Framework Agreement solidified the coming shift in the United States' relationship with Iraq, from one of patronship to one of partnership.

EMBRACING IRAQI SOVEREIGNTY

On taking office, President Barack Obama followed his campaign pledge to end the Iraq war while honoring the SOFA signed with Iraq's government under the Bush administration. He engaged in an extensive policy review with Odierno, taking into consideration the opinions of those who thought that only a small residual force was necessary in Iraq as well as the ideas of those who argued that a defined pullout date would simply encourage the insurgents to lie low until U.S. forces departed. Obama chose the middle ground, ordering the end of combat operations and the reduction of U.S. troops to 50,000 by August 2010. The decision gave Odierno the flexibility he desired, within set deadlines, to determine the pace of the troop withdrawal so that he could respond to any military or political contingencies, such as parliamentary delays in holding elections or forming a goverment. Odierno implemented Obama's plan by shifting the mission of the remaining U.S. forces from counterinsurgency to stability operations, focusing on bolstering the ISF's capacity to protect the Iraqi people on their own.

The U.S. military required significant physical and strategic restructuring to accomplish this transformation. As we discussed how to make those necessary adjustments, Odierno and I began with the premise that the struggle in Iraq was essentially political. We agreed that the U.S. military could assist by training the ISF and preventing conflict but that only the Iraqis themselves could solve the underlying issues plaguing their country: tensions between Arabs and Kurds, Shiites and Sunnis, and local provinces and the national government. Although security in Iraq had greatly improved, the country had merely gone from being a failed state to being a fragile state, still beset with poor public services and subject to the pervasive influence of armed groups and foreign powers. As a result, Odierno instructed his commanders that the troop drawdown should not become the overriding focus of their mission. The United States had to help the Iraqi government develop the necessary state institutions to function properly on its own. Brigades were reorganized to further that goal, enabling U.S. State Department-led transition teams to build administrative capacity in provincial and local governments throughout Iraq.

Odierno provided his subordinates with the flexibility to determine when conditions in their respective areas were ripe for the shift. U.S. troops had to embrace Iraqi assertions of sovereignty as a sign of progress, even when they sometimes conflicted with U.S. advice. They also had to accept that the ISF were never going to be as proficient as U.S. troops. Odierno explained that the United States sought a strategic partnership with Iraq and that the way in which U.S. forces left the country would influence the long-term relationship between the U.S. and the Iraqi governments.

Odierno traveled the country to obtain on-the-ground progress reports from his commanders, considering it a success when they showed an in-depth understanding of what could cause instability in their areas and when they reported on how they were working closely with their U.S. civilian colleagues to address those issues through reconstruction project funds and technical assistance. Odierno encouraged his commanders to describe progress being made by the ISF in terms of the forces' relations with the local population, the operations they conducted, the circumstances in which they had requested U.S. assistance, and what further training they required.

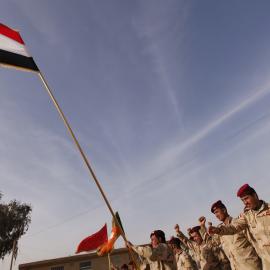

As I prepared to depart Iraq in August 2010, it was clear that the close partnership between the U.S. military and the ISF had paid dividends. Accompanying Odierno as he toured the country to review the progress, I witnessed U.S. and ISF soldiers celebrating each time the United States transferred one of its bases to Iraqi forces, conducting ceremonies in which U.S. commanders symbolically delivered the keys to their Iraqi counterparts. The strong individual and institutional relationships between the two forces contributed to a growing sense of security across the country.

CHANGING ROLES

U.S. forces surveyed their respective regions for disruptive elements that could undermine the calm. Communal struggles persisted between Arabs and Kurds and Shiites and Sunnis; state institutions remained weak, as the central government and the provinces negotiated power-sharing arrangements; foreign powers, especially Iran (as well as Syria and Turkey), continued to meddle in Iraqi politics; and extremist groups, such as the remnants of al Qaeda and lingering Shiite militias, continued to foment trouble. Odierno understood that the very presence of U.S. troops could fuel instability, as groups would attack them in an attempt to gain credit for the impending U.S. withdrawal.

By viewing post-surge Iraq through this prism, the U.S. military focused its actions to provide the necessary resources and advice to those Iraqis attempting to smooth the points of friction. In September 2008, for instance, tensions arose between Arabs and Kurds in the northern Iraqi region of Diyala, and followed several months later in Kirkuk and Ninewa. The two sides came close to armed conflict over control of disputed territories in northern Iraq, which the Kurdistan Regional Government was seeking to incorporate within its federal region. The ISF and the Kurdish Pesh Merga (security forces) viewed each other with increasing suspicion and focused their energies on each other, allowing al Qaeda to exploit the situation by attacking various religious minority groups, including Christians, Shabaks, and Yezidis. Only mediation by U.S. officers prevented fighting from breaking out between the ISF and the Pesh Merga. At the request of Maliki and Massoud Barzani, president of the Kurdistan Region, Odierno devised a system of cooperation among the ISF, the Pesh Merga, and U.S. troops in operational centers, at checkpoints, and during patrols. This helped establish relationships between the leaders of the various forces, building mutual trust and confidence and restoring stability to the disputed territories.

As the June 2009 deadline for U.S. soldiers to leave Iraqi cities approached, Odierno accompanied Iraq's minister of defense, Abdul-Kader al-Obeidi, and minister of the interior, Jawad al-Bolani, around the country to assess the security situation and the ISF's performance. It was clear that security was continuing to improve and that joint operations with U.S. forces were hastening the ISF's development. After some initial growing pains, communication and collaboration between the U.S. military and the ISF had allowed Iraqi soldiers to take the lead, with U.S. forces largely providing background support. Although conditions varied across the country -- in Basra, the ISF had largely taken command, whereas in Ninewa, U.S. soldiers compensated for a lack of adequate Iraqi forces by continuing their combat operations against al Qaeda -- nearly all U.S. units had undertaken the transition from counterinsurgency to stability operations by early 2010, months ahead of schedule.

The implementation of the SOFA proceeded far more smoothly than either Iraqi or U.S. leaders had anticipated. In order to be ready to address potential violations of the agreement, the U.S. and Iraqi governments had established a number of joint committees covering a spectrum of security issues, including military operations, detainee affairs, and airspace control. There were only a few initial complaints issued by Iraqis about suspected U.S. violations of the agreement. Despite the initial fears of the U.S. military leadership, no U.S. soldier was ever arrested by the ISF and no issues of jurisdiction arose regarding U.S. soldiers. Meanwhile, the United States adhered strictly to the withdrawal timeline established by the SOFA, showing the Iraqis that the United States had no intention of occupying their country indefinitely. The deadline forced the U.S. military to relinquish power and allowed the Iraqis to assume command more quickly than might otherwise have happened. The United States demonstrated that it would leave with dignity, in partnership with the Iraqi government rather than under fire from insurgents.

The development of strong individual and institutional relationships between U.S. and Iraqi troops will likely continue as the two countries work to establish a long-term relationship. The rights and wrongs of the Iraq war will be debated for years to come. What will not be disputed, however, is the way in which the U.S. military learned from its initial blunders, adapted, retrained and reeducated its soldiers, transitioned seamlessly from counterinsurgency to stability operations, and strengthened the capacity of Iraqi forces.

THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES

Despite the successful transition from the surge to sovereignty in Iraq, challenges remain on the horizon for internal Iraqi politics and the U.S.-Iraqi relationship. The fraught formation of a governing coalition following Iraq's March 2010 national elections revealed how fragile the country's political institutions remain. Although Iraq's 2009 provincial elections had brought the Sunnis into local government and promoted reconciliation, the 2010 contest saw friction once again. Maliki accused former elements of Saddam Hussein's Baath Party, along with Syria, of masterminding continued attacks in Iraq. Some Shiite politicians, supported by Iran, sought to weaken the nationalist, nonsectarian Iraqiya Party, led by Ayad Allawi, by attempting to disqualify its candidates as former Baath Party members.

The Iraqiya Party overcame these challenges and narrowly won the election, with 91 seats, gaining the votes of most Sunnis and of a sizable proportion of secular Shiites. Maliki's Dawa Party came in a close second, with 89 seats, and for the next nine months, the two factions left Iraq in political limbo, with each side seeking to secure a majority in parliament in order to form a coalition government. Ironically, both the United States and Iran supported Maliki's bid to remain prime minister; U.S. leaders sought to broker a power-sharing arrangement between the two parties to keep Sadr's followers out of the government and strengthen reconciliation, whereas Iran hoped for a Shiite-dominated coalition. Maliki and Allawi grudgingly came to terms this past December, with Maliki retaining his post as prime minister and Allawi becoming head of the newly created National Council for Higher Policies, the purview of which remains uncertain.

Although a government has been formed, Iraq's political factions sadly missed an opportunity to secure the public's belief in the democratic system. Instead of demonstrating a peaceful transition of power and unity, the process revealed the lingering mistrust within Iraqi society, particularly among the ruling elites, who appeared ready to elevate their personal interests above the national good. Meanwhile, Iraqis remain skeptical of the large and unwieldy coalition assembled by Maliki, which enjoys few points of agreement and will have difficulty grappling with politically sensitive issues, such as federalism, the sharing of oil revenues, and the demarcation of internal borders. True reconciliation among Iraq's ethnic and religious groups thus remains elusive, and what progress has been achieved so far could unravel.

Meanwhile, the Obama administration's rhetorical emphasis on the troop withdrawal -- meant for a domestic audience -- has largely overshadowed the quiet but burgeoning strategic partnership between Iraq and the United States. Washington needs to devote adequate attention and resources to furthering the Strategic Framework Agreement, which established the basis for possible long-term cooperation between the two countries. Iraqi politicians from all communities, save the Sadrists, have voiced concern that the United States is too focused on withdrawing from Iraq, placing stability before democracy and strengthening Maliki's ability to maintain control of the country through the ISF rather than through the consent of Iraq's politicians or public. They have also expressed concern about Iran's ambitions and aspirations in Iraq -- an issue that will loom over the country for years to come.

Iraq still has a long way to go before it becomes a stable, sovereign, and self-reliant country. Continued engagement by the United States can help bring Iraq closer to the American vision of a nation that is at peace with itself, a participant in the global market of goods and ideas, and an ally against violent extremists. Under the terms of the Strategic Framework Agreement, the United States should continue to encourage reconciliation, help build professional civil service and nonsectarian institutions, promote the establishment of checks and balances between the country's parliament and its executive branch, and support the reintegration of displaced persons and refugees. U.S. assistance is also needed to bolster Iraq's civilian control over its security forces, invest in the country's police units, and remove the Iraqi army from the business of policing. Should Washington fail to provide such support, there is a risk that Iraq's different groups may revert to violence to achieve their goals and that the Iraqi government may become increasingly authoritarian rather than democratic -- undermining the United States' enormous investment of blood and treasure.

This article is part of the Foreign Affairs Iraq Retrospective.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions