SINCE the middle of the last century, the American labor movement has been in steady decline. In the early 1950s, around one-third of the United States' total labor force was unionized. Today, just one-tenth remains so. Unionization of the private sector is even lower, at five percent. Over the last few decades, unions' influence has waned and workers' collective voice in the political process has weakened. Partly as a result, wages have stagnated and income inequality has increased.

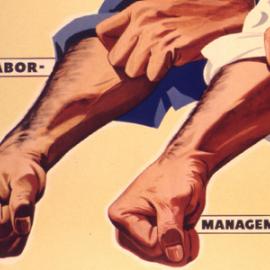

The decline of American unions was not preordained. The modern labor movement first emerged in response to the Great Depression, when fledgling workers' organizations and established unions led mass protests against unemployment and the failures of American capitalism. Tumultuous strikes rocked the heartland from the coalfields of Pennsylvania to the factories of Michigan. In those days, "anybody struck," as the labor historian Irving Bernstein once observed. "It was the fashion." In 1935, a key component of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, the National Labor Relations Act, codified workers' rights to form and join unions.

As many workplaces unionized in the following years, labor leaders sought to establish themselves as responsible social and political partners. Indeed, when World War II came, they often chose to forgo strikes in the name of the war effort. Such moves sometimes proved unpopular with ordinary workers, but they helped win union leaders seats at the policymaking table and cemented their organizations' status as the largely uncontested representatives of the United States' industrial laborers. By 1954, more than 17 million American workers, around 35 percent of all wage and salary earners, were union members. In Indiana, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Washington, and West Virginia, unionization was 40 percent or higher. Even in the South, where the labor movement met the greatest resistance, union membership got as high as 20 percent of workers in Alabama, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Tennessee. U.S. union members were disproportionately male blue-collar breadwinners working lifelong jobs in large firms. As organized labor helped secure the economic well-being of this group, the American middle class prospered and the country entered a golden age of income equality.

At its height, labor was both politically and economically powerful. In the realm of politics, unions often spoke on behalf of a range of workers, including those who did not belong to unions. And economically, they contributed broadly to social welfare by helping push up wages as worker productivity rose. In doing so, they underwrote the affluence of the American working class in the 1950s and 1960s. With labor's decline since, economic elites have grown more influential in the political system and the tie between national economic prosperity and working-class prosperity has been severed. Rebuilding the power of working people -- if it is still possible -- will need to involve reviving labor's dual economic and political role. Unions must start by speaking up on behalf of those most hurt by wage stagnation and rising inequality. Economically, unions must contribute more actively to the prosperity of firms and communities struggling with the effects of the recession and global competition.

THE RUST AGE

Although the National Labor Relations Act was initially a boon for unions, it also sowed the seeds of the labor movement's decline. The act enshrined the right to unionize, but the system of workplace elections it created meant that unions had to organize each new factory or firm individually rather than organize by industry. In many European countries, collective-bargaining agreements extended automatically to other firms in the same industry, but in the United States, they usually reached no further than a plant's gates.

As a result, in the first decades of the postwar period, the organizing effort could not keep pace with the frenetic rate of job growth in the economy as a whole. Between 1950 and 1979, the labor force nearly doubled, adding around 45 million new wage and salary earners. Union membership increased by only half in the same period, however, from 14 million to 21 million workers, shrinking the percentage of union members in the labor force from 30 to 20 percent. By the 1970s, new organizing could annually capture only about one-third of one percent of the nonunion labor force, which itself was growing at three percent a year.

Even if the labor market had simply continued expanding with no broader changes in the economy or politics, organized labor would have struggled to sustain its influence in the 1970s and beyond. As it turned out, however, economic and political conditions got much worse. The OPEC oil embargo of 1973-74 heralded a decade of turmoil. Oil price shocks precipitated worldwide stagflation. Western Europe and the United States were gripped by widespread joblessness and a slowdown in productivity growth. As the 1970s and 1980s unfolded, U.S. manufacturers also faced increasing competition from European and Japanese exporters in the heavily unionized aerospace, auto, and steel industries. During the same period, the government deregulated the transportation and telecommunications industries and relaxed price controls, licensing regulations, and restrictions on market entry. To save jobs, unions often made concessions, including accepting pay cuts and pay freezes, lower cost-of-living wage adjustments, and shorter contract periods.

By the 1980s, the unionized share of the work force had been steadily shrinking for three decades. From that point on, the number of union workers began to decrease in absolute terms, particularly in the communications, manufacturing, transportation, and utilities industries. In the trucking sector, deregulation opened the door to new nonunion firms and independent owner-operators. Some firms, such as Toyota's U.S. operation, built new union-free plants in the South, far from labor's historic bases in the Midwest and the Northeast. Subcontracting to small, specialized producers also added to the growing tally of nonunion jobs in manufacturing.

Labor's decline was not set off by impersonal market forces alone. In the 1970s and 1980s, difficult economic conditions and the growing cost of union contracts led many employers to adopt illegal tactics to fight organizing attempts. Frequent labor law violations included discrimination, coercion, and the dismissal of workers who were known to support unionization. Even as union organizing activity remained nearly constant, the number of complaints about unfair labor practices filed with the National Labor Relations Board roughly doubled. Many of these claims proved successful; between 1970 and 1980, the number of workers reinstated to their jobs or granted back pay after filing unfair-labor complaints quintupled. As the political scientists Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson write in their book Winner-Take-All Politics, companies came to view these penalties as "simply a cost of doing business, and far preferable to successful unionization."

Employers prevented unionization through legal means as well. As in previous decades, labor laws permitted managers to hold mandatory antiunion meetings with workers, distribute antiunion literature, and delay the negotiation of labor contracts following successful organizing drives. What changed was employers' willingness to deploy such tactics. Over time, they became almost reflexive responses to the threat of unionization. In combination with unlawful tactics, and advised by a flourishing industry of union-busting consultants, employers managed to stifle labor organizing, and union election activity plunged in the early 1980s.

In response, unions tried to reform national labor laws to make organizing easier. Yet because of the growing political clout of big business, every major effort to change the labor laws since the 1960s has failed. Opposition to unions had spread from executive suites to the White House. Months after Ronald Reagan's presidential inauguration, in the summer of 1981, some 13,000 air traffic controllers went on strike to demand better working conditions, higher pay, and a 32-hour workweek. In a tense showdown, Reagan fired the strikers and hired permanent replacements. Unions bowed before this and later onslaughts, and strike activity declined by over two-thirds during the 1980s and 1990s.

To be sure, the unions themselves often added to their troubles. U.S. labor relations were adversarial; unlike some of their European counterparts, American unions were unable to develop collaborative relationships with employers to improve training or management decisions. Labor's record as a politically progressive force was also uneven. Unions maintained only an arm's-length relationship with the civil rights movement, the women's movement, and the protest movement against the Vietnam War. And declining membership only made unions more defensive. As the organized fraction of the total work force plummeted, unions lost power, which made them less able to influence policy and attract workers.

NICE WORK IF YOU CAN GET IT

The American labor movement would have fallen further and faster if not for public-sector unionization, which rose sharply throughout the 1970s. By the 1980s, nearly 40 percent of government workers were in unions, and the proportion has remained roughly constant until today. The figures are most striking in local government. Over half of all teachers, firefighters, and local police are union members, a rate ten times as high as that in the private sector.

In part, the strong presence of unions in the public sector reflects the dynamics of government employment. Public institutions do not die like private firms; new public-sector jobs tend to be in already unionized workplaces. Compare that to the private sector, in which new jobs are generally in new nonunion firms. Furthermore, since public-sector employees provide government services, they are largely sheltered from competition. Nonunionized schools, for example, will not drive the public education system (and its unionized teachers) out of business. In the public sector, the threat to unions comes not from the market but from the antilabor sentiment that has gripped elected officials.

After the financial crisis of 2008 and the remarkable electoral success of the political right in 2010, many newly elected Republican governors in highly unionized states launched a coordinated offensive against public-sector unions. These initiatives have gone furthest in Wisconsin, where, starting in February 2011, Scott Walker, the Republican governor, pushed forward legislation to eliminate collective-bargaining rights for many public-sector workers. The bill passed in March 2011 and, after surviving a series of legal challenges, went into effect that summer. Walker's charge was driven by both economics and politics. Wisconsin, like many other states, needed to balance its budget and saw weakening the public-sector unions as a way to reduce government expenditures. Republicans also knew that they would benefit if unions, which form an important financial and organizational base for the Democratic Party, were diminished.

Other GOP governors, such as New Jersey's Chris Christie, seem to have followed a similar logic. Christie has radically restructured state employee contracts, increasing workers' retirement age and forcing workers to contribute much more to their health-care and retirement plans. His scheme also restricted unions' bargaining rights over benefits for the next four years, a provision that he says will help right New Jersey's listing economy but one that labor believes is a stealth measure intended to accomplish what Walker has done in Wisconsin.

So far, however, Christie and many of his colleagues in other states have avoided the most extreme elements of Walker's strategy, sensing that in such a fragile economic climate, aggressively trying to bust public-sector unions would carry too much political risk. The leading Republican presidential candidate, Mitt Romney, for example, senses the perils of the issue. This past fall, he refused to take a stance on an Ohio ballot initiative seeking to overturn a law curtailing public-sector union rights. Still, Walker's fight could help erode the taken-for-granted unionization of state and municipal workers. Both Christie and Romney have expressed support for Walker's effort. Despite the radical nature of Walker's attack on unions, his popularity remained near 50 percent in Wisconsin and around 90 percent among Wisconsin Republicans.

GOING PUBLIC

Public workers may be unhappy with these recent trends, but not everyone is mourning labor's decline; mainstream economic theorists see the benefits of union membership as too expensive in today's economy. Many of them argue that outsized union wages reduce employment and lead to higher prices for consumers. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Gary Becker, for example, has written that unions are slowing the United States' economic recovery and making it harder for the country to compete overseas. In fact, unionization imposes only a modest drag on the economy. The economists Richard Freeman and James Medoff have calculated that in 1980, when a quarter of the work force was covered by collective-bargaining agreements, organized labor reduced the gross national product by just one-fifth to two-fifths of one percent.

The social and economic benefits of unions outweigh such costs. For one, research shows that union membership in the private sector increases a worker's compensation by 10-20 percent. In other words, in terms of wages, belonging to a union is roughly equal to having a college degree. Unions also equalize pay within companies, partly because they raise the wages of blue-collar and less-skilled workers and partly because they standardize pay among workers with similar educational achievements and experience.

Even more important, unions also improve pay outside their own workplaces. Nonunion employers in highly unionized industries, for example, often raise the wages they pay to avert organizing efforts. Even after accounting for demographic, educational, and regional differences in local labor markets, wage inequality is significantly lower among nonunion workers in areas and industries that are highly unionized. In addition, adjusting for local economic conditions and the dominant party affiliations of state legislatures, highly unionized states have higher minimum wages and more generous welfare benefits and spend more on education. Legislators in these states are also more likely to vote for minimum-wage increases, and poverty rates in these states tend to be lower.

The benefits of unions protected American workers for more than half a century. The landmark development came in 1948, when General Motors and the United Auto Workers negotiated what came to be known as the Treaty of Detroit. The agreement approved an annual cost-of-living wage increase plus an additional annual increase of two percent. The cost-of-living adjustment ensured that wages would at least keep up with inflation. The extra two percent compensated workers for productivity boosts that came along with technological change. Also, from the presidency of Dwight Eisenhower through that of Jimmy Carter, successive administrations granted union representatives seats on national boards that set wage guidelines. Although the wage boards were chiefly charged with controlling inflation, they also had a role in ensuring equality. Because the labor market was more highly regulated in those days than it is today, pay rates across the whole economy tended to rise and fall together, so wage inequality was tightly controlled.

As unions started to make concessions to big business in the lean days of the early 1980s, however, the Treaty of Detroit formula was abandoned. In an influential 2009 paper, "Institutions and Wages in Post-World War II America," the MIT economists Frank Levy and Peter Temin described the emergence in the 1980s of what they called "the Washington Consensus," an era of deregulation in which earnings inequality increased. As the decline of unions accelerated in those years, wage bargaining became more defensive. New union workers were given less favorable contracts, and lump-sum payments commonly replaced regular wage increases. As the fraction of all income captured by the top one percent of earners more than doubled, middle-class pay stagnated for the first time in decades; from 1973 to 2009, the median hourly wage increased by less than ten percent, even though nonfarm productivity ballooned by about 70 percent.

The overall benefits unions have brought have fluctuated with economic conditions, but by one set of estimates, they have decreased over time, from around 26 percent in the early 1980s to 20 percent by 2000. In turn, in the same period, unions' standardizing effect on wages diminished; overall inequality increased substantially among union and nonunion workers alike: by 40 percent among men in the private sector. By our calculations, around one-third of that jump was directly related to declining unionization. (The effect on women's wages was somewhat smaller because they were less likely to have joined to begin with.) Moreover, as union membership declined, businesses awarded more generous nonwage compensation -- health and retirement benefits and vacation pay -- to salaried workers with college degrees or higher.

In the last decade, power has shifted even more from workers to managers and owners. The economic guarantors of a good middle-class life, namely, stable wage growth and generous benefits, have eroded. Although union workers still enjoy higher wages, better benefits, and a greater voice at work, their advantages are smaller than in the past. And because those advantages are confined to a shrinking group of workers, future generations of workers can look forward to tougher economic times than their parents.

THERE IS VOTING POWER IN A UNION

In their heyday, American unions routinely played a major political role. They emptied their coffers and flexed their substantial organizing muscle to counteract the influence of the business lobby in presidential, congressional, and local elections. Labor leaders enjoyed privileged access to politicians, especially Democratic officials, and were instrumental in developing progressive domestic programs, such as Medicare.

The strong link between organized labor and the Democratic Party extended down to the union rank and file. For example, in the 1964 presidential election -- a high-water mark for the link between unions and the Democratic Party -- nearly 90 percent of union members cast their votes for Lyndon Johnson. After Johnson's victory, the Republicans realized that the labor vote was simply too large and politicized to ignore. According to the Nixon administration in the early 1970s, "No program works without labor cooperation."

Beyond supporting policies that protected workers' interests, unions also amplified their members' voices. In the United States, as elsewhere, the poorer a person is, the less likely he or she is to be politically involved. But unions encouraged their members, many of whom were blue-collar, to vote, thus drawing otherwise atomized individuals into an organization and providing them with the training and resources necessary to pursue collective goals. Research consistently demonstrates that the voter-participation rates of union members are about five percentage points higher than those of otherwise similar nonmembers. Unions are among the few organizations that have been able to mobilize the less advantaged on such a large scale.

Labor retains this ability to mobilize today, but the labor vote itself has weakened, for several reasons. First, decades of declining membership have meant a shrinking base to rally. Although belonging to a union remains a strong indicator of whether a person will vote, unions' total impact on elections has been greatly reduced. In the upcoming election, for example, union support for President Barack Obama, in the form of money and manpower, is less important than it would have been for Democratic candidates in years past. Second, unions' effect on political mobilization has always been stronger among private-sector workers than public-sector ones. On average, public-sector workers are better educated and so are already more likely to go to the polls. Unions influence these workers' voting habits far less than they do those of private-sector employees. In the 2008 presidential election, for example, among public-sector workers, those in unions were no more likely to vote than those not in unions after accounting for other key predictors of voting. Unions' effect on voting among private-sector workers remained significant, but because public-sector workers make up a majority of union membership today, the number of workers that labor mobilizes on Election Day is low and falling.

Labor's decline has effectively left millions of nonunion working-class Americans without the organizational ties often necessary to participate in politics. Further, since unions no longer represent broad sections of the nation's blue-collar workers, unions are now taken less seriously; indeed, many policymakers, including labor's remaining allies, have come to view labor as just another special interest vying for influence. Although many unions remain fairly well funded, they will never be able to compete with corporate donations. In the hotly contested 2000 election cycle, business-related interests outspent organized labor by a ratio of 14 to one, and the ratio has been similar in more recent contests. The labor movement was once able to compensate for the financial power of the business lobby through its advantage in manpower. Not so any longer.

REVIVING THE GOLDEN ERA

Labor unions underwrote the affluence of the American working class in the twentieth century. They ensured that manual work paid white-collar wages and gave a collective voice to workers in the political process. The story of labor's decline is often told with an air of inevitability; unions became outmoded as American capitalism became more dynamic. In such an account, the consequences of deunionization -- rising inequality, wage stagnation, and declining political participation -- appear equally inevitable.

But the story has not played out the same way everywhere. The turbulent economic conditions of the 1970s affected all the advanced economies. In the small, trade-dependent economies of Scandinavia, highly centralized unions were able to restrain wage growth, curb inflation, and maintain employment. In Germany, unions expanded their role in workplace governance and the training of skilled workers. Although the proportion of union members among workers did decrease in western Europe during this time, it did so far less than in the United States. And the coverage of collective-bargaining rights generally held steady. European labor unions still represent a broad constituency of workers and actively contribute to their countries' economic success. Moreover, although some claim otherwise, unions have not made the global economic crisis there worse. Where national unions have historically had a role in macroeconomic management -- in Belgium and the Netherlands, for example -- negotiations over wages and working hours helped head off big increases in unemployment in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

American unions have faced the same challenges as European ones but have struggled far more. U.S. labor is more insular than its European counterparts and more fragmented. The American labor movement's decentralization has prevented the kind of broad wages-for-employment bargains that European unions have been able to negotiate with employers and governments. Sweden provides the clearest example, where, through national-level collective bargaining, unions restrained wage growth from the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s in response to pressures on inflation and unemployment. Unionization in the United States has been more expensive for individual employers. In the 1970s and 1980s, it was also vulnerable to employers' divide-and-conquer strategies, through which business owners squeezed organized labor by threatening to shift their operations to nonunion establishments.

Although labor in the United States is on the ropes, the current era of slow wage growth (and, now, high unemployment) might provide an opportunity for its revival. "Inequality" has entered the American political lexicon, partly as a result of the Occupy Wall Street protests that began in mid-2011. Their message will be difficult to sustain, however, without an institutional supporter intent on politicizing the problem of inequality. Of course, inequality is just one of a number of adverse trends. For decades, wages have trailed productivity, attempts to reform labor laws have consistently failed, and, most recently, the government has bailed out banks rather than households. These developments suggest an economic game that has become rigged against working-class Americans. If unions speak out about these economic injustices, they can reclaim their historic role as advocates for a broad range of working people.

The U.S. labor movement will not recover the vitality of its golden era, which was forged in the mobilizations and social legislation of the 1930s. But it could wage a frontal attack on the problem of inequality and revive its legitimacy by speaking on behalf of broad economic interests and appealing to the millions of households hurt by wage stagnation and a diminished political voice. Boldness on the issue of inequality, along with greater inclusivity, could help reverse declining union membership. Indeed, recent successes in labor organizing, such as the Justice for Janitors campaign among immigrant workers in Houston and Los Angeles, have shown the effectiveness of working with community organizations and waging wide campaigns for social justice.

A more politicized brand of unionism, interested in more than just preserving the economic privileges of union members, would stand out as one of the few remaining defenses of working-class affluence and economic opportunity. Of course, unions' claims will be more persuasive if the benefits of unions become more immediately visible. To reverse the perception, and sometimes the reality, that unions care about only their members, labor must take on the challenge of improving productivity and profitability at the local level. In other times and places, unions have played major roles in recruiting and training new workers and in ensuring community well-being outside the firm.

A national campaign against inequality coupled with productivity-centered labor relations at the local level would reflect the lessons of recent labor history. Unionism has been sustained where organized labor has represented broad constituencies and where it has been a vital participant in national economic performance. Reviving that kind of unionism would recall the days in which the economic security and mobility of working people hung on labor. The challenges are formidable. Economic globalization and intense employer opposition make labor's revitalization especially difficult. Yet a rejuvenated labor movement is central to greater economic security and opportunity for working people.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions