A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico. By Amy S. Greenberg. Knopf, 2012, 344 pp. $30.00 (paper, $16.95).

Every country sooner or later confronts the sins of its past, though rarely all at once. In recent decades, historians of the United States have revealed and explored the sins of American imperialism, recounting in detail Washington’s interventions in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East. Yet they have largely overlooked American meddling in Mexico. Consequently, few in the United States recognize that the Mexican-American War (1846–48) was Washington’s first major imperialist venture. Fewer still would understand why future U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant, who fought in Mexico as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army, would come to see it as the country’s most “wicked war.”

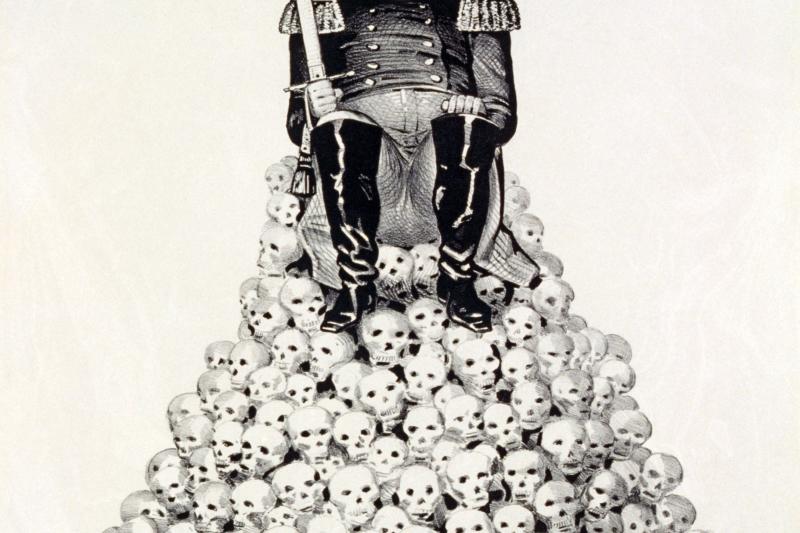

For Mexicans, the war was a national catastrophe. Their sense of depression receded nearly 20 years later, when Mex ican forces fought off a second foreign occupation by France under Napoleon III. Yet the U.S. invasion was too harrowing to forget. It became institutionalized in national myth: in the heroic legend of the Niños Héroes, the boy martyrs of the war’s final battle, at Chapultepec; in the many monuments at the sites of major battles; and in the museums that house relics of the Mexican resistance. Today, one still sees traces of the war in the defensive and distrustful character of Mexican nationalism. For more than a century and a half, Mexico has remained deeply suspicious of its northern “gringo” neighbors, who might yet seize another slice of territory at a moment’s notice.

CHARACTER DRAMA

In recent decades, a number of worthwhile books have been published, in both Mexico and the United States, on various aspects of the war. Most, however, have been intended for academic audiences. Greenberg’s is the first that offers the kind of narrative history that, with sensitivity and balance, introduces the general reader to this remote and largely forgotten drama. It does so by telling the story of the war through the lives of a selection of Americans whose careers it shaped, including U.S. President James Polk, the once and future U.S. senator Henry Clay, and then U.S. Congressman Abraham Lincoln. In Polk, Greenberg identifies an ideology of national supremacy that led to the outbreak of war and shaped its course; through her portrayal of Clay and Lincoln, she gives voice to the war’s opponents.

In 1846, war was only one of Polk’s options for resolving a number of disputes with Mexico, chiefly over unpaid Mexican debts and the contested southern border of Texas, which the United States had annexed just a year earlier. But Polk never seriously considered any alternatives. Indeed, Greenberg argues that Polk’s image of himself as an armed prophet of manifest destiny was itself the most decisive factor in the outbreak of the war. Polk was fully convinced, Greenberg writes, that “it was God’s will that Mexico’s richest lands, especially the fertile stretch by the Pacific, pass from its current shiftless residents to hard-working white people better able to husband their resources.” When a Mexican cavalry unit attacked a U.S. patrol in a disputed area near the Rio Grande, Polk saw an opportunity to serve his own version of divine justice.

Greenberg argues that Polk’s view of the conflict grew out of his experience as a slave owner. Like many Americans who owned slaves in the 1840s -- and many who did not -- Polk, in large part due to the influence of his wife, Sarah, believed that God had ordained white supremacy. In her memoirs, Sarah recalled telling her husband one afternoon at the White House that “the writers of the Declaration of Independence were mistaken when they affirmed that all men are created equal.” Her slaves had not chosen “such a lot in life, neither did we ask for ours; we are created for these places.” Her husband, she wrote, was so persuaded that he often cited the conversation to praise her “acumen” on the topic.

To Polk, the intrinsic inferiority of the Mexicans helped justify the use of force against them and even helped explain why they could not repay their debts and why, unlike the French and the Spanish, they remained resistant to selling the United States territory that Polk believed they were not capable of populating, cultivating, or governing properly.

Although a majority of the American electorate shared Polk’s ideology of racial supremacy, an unlikely coalition of prominent political figures opposed the war from the start. Dissenters included the pro-slavery U.S. senator from South Carolina John C. Calhoun; former U.S. President John Quincy Adams, who characterized the “outrageous war” as a plot by the slavery states to dominate Congress; and even the commander of the U.S. forces at the border and future U.S. president Zachary Taylor, who believed the annexation of new lands to be “injudicious in policy and wicked in fact.”

But a national propaganda campaign won over the public by portraying the war as a great national cause. Politicians, principally southerners, made the case for war in the popular press. In 1846, the New Orleans Daily Delta warned that without “active measures” against Mexico, “every dog, from the English mastiff to the Mexican cur, may snap at and bite us with impunity.” Pro-war fervor spanned the political spectrum: one of its most articulate advocates was Walt Whitman, then a newspaper editor in Brooklyn, who urged his countrymen to “teach the world that, while we are not forward for a quarrel, America knows how to crush, as well as how to expand!”

In Mexico, too, newspapers expressed a sense of wounded pride. La Voz del Pueblo called on the nation to “destroy the unjust usurpers of our rights.” Mexican President José Joaquín Herrera, warning of the costs that revenge would carry, attempted to avoid war through diplomacy, but military hard-liners staged a coup and overthrew him. The overwhelming national sentiments, however, were anxiety and fatalism. “To our detriment the war has begun and we must not lose time,” wrote one commentator in the newspaper El Republicano. War was the last thing Mexico wanted, but it was also the only honorable response to U.S. aggression.

STARS AND STRIPES

The fighting lasted from April 25, 1846, until September 14, 1847, when Mexicans saw, in the words of one eminent Mexican historian, “the hated banner of the stars and stripes” waving over their center of government, the Palacio Nacional, in Mexico City.

From the beginning, the U.S. military dominated events. In 1846, two separate U.S. contingents executed a pincer movement, by sea and by land, to capture the ports of Alta California and the territory of Nuevo México. In early 1847, Taylor swept through the north of Mexico in a series of bloody encounters until he met the regular Mexican army under General Antonio López de Santa Anna in the first full-scale battle of the war, at La Angostura. Although the battle had no decisive victor, the American public came to see Taylor as a hero (enough to elect him Polk’s successor as president). Polk, who distrusted Taylor, eventually decided to transfer part of Taylor’s forces to the command of General Winfield Scott, who went on to retrace the route to Mexico City taken by the conquistador Hernán Cortés in 1519. Many U.S. soldiers saw themselves as the heirs to the Spanish, and some even carried a copy of William Prescott’s book on the Spanish conquest of Mexico. After winning the decisive battle of Cerro Gordo in April, U.S. forces entered the Valley of Mexico in the middle of August and fought four major battles -- at Padierna, Churubusco, Molino del Rey, and Chapultepec -- before seizing Mexico City.

Among the many merits of The Wicked War, two are especially impressive: Greenberg’s use of personal testimonies and her portrayal of atrocities committed by U.S. forces -- events that have been little reported, even by Mexican writers. Greenberg uses a first-person account, for example, to describe a massacre of Mexican civilians by volunteer soldiers from Arkansas: "The cave was full of volunteers, yelling like fiends, while on the rocky floor lay over twenty Mexicans, dead and dying in pools of blood, while women and children were clinging to the knees of the murderers and shrieking for mercy. . . . Nearly thirty Mexicans lay butchered on the floor, most of them scalped. Pools of blood filled the crevices and congealed in clots."

Such events troubled many U.S. officers, including Scott. In an 1847 letter to the U.S. secretary of war, Scott reported that men under Taylor’s command had committed crimes that were “sufficient to make Heaven weep.” U.S. militiamen had raped mothers and daughters in the presence of their tied-up husbands and fathers, he wrote, “all along the Rio Grande.” Yet as U.S. forces readied their attack on Veracruz, Scott denied requests by European consuls to allow women, children, and the elderly to evacuate the city. He would mercilessly bombard the city, destroying houses, churches, and hospitals. In a letter to his wife, the U.S. Army captain Robert E. Lee, who was at Veracruz and who would later lead the Confederate army during the Civil War, wrote that his “heart bled for the inhabitants.”

Greenberg argues that U.S. atrocities in Mexico echoed those of the Indian Wars of the 1830s, including a massacre of Cherokees in 1838, in which Scott participated. “When faced with a ‘treacherous race,’ the rules of war did not apply,” Greenberg writes of the attitude of American commanders. The U.S. public seemed to agree. The New York Herald predicted that “like the Sabine virgins,” Mexico would “soon learn to love its ravisher.” But the love never came, the slaughter continued, and Mexican troops made the American invaders pay dearly in blood. Although estimates differ, Greenberg reports that the United States sent 59,000 volunteers and 27,000 regular troops to fight the war; nearly 14,000 of them died. Of course, the price was even higher for Mexican citizens; estimates suggest that as many as 26,000 died during the war.

The bloodshed fed growing opposition to the war in the United States. Clay, whom Polk had defeated in the presidential election of 1844, emerged as the war’s most powerful opponent in Washington. Clay led the Whig Party, which had opposed the annexation of Texas, believing -- correctly, it turned out -- that it would lead to conflict. By 1847, Clay’s opposition had taken on a personal dimension: his son, a graduate of West Point, was killed in February of that year at the Battle of Buena Vista. In a speech to a crowd of thousands in Lexington, Kentucky, only a few weeks later, Clay condemned Polk’s war of “unnecessary and offensive aggression” and its “dreadful sacrifices of human life.” He also asked Americans to consider Mexico’s point of view. It was Mexico, he argued, that was “defending her fire-sides, her castles and her altars.” Making a comparison closer to the American consciousness, Clay drew a parallel with Ireland and the United Kingdom: “Every Irishman hates, with a mortal hatred, his Saxon oppressor,” he said.

Clay might not have realized just how apt his analogy was. In September 1846, a small contingent of U.S. soldiers, nearly all recent immigrants from Ireland, had actually switched to the Mexican side. They had changed their allegiance after their first battle, motivated by the plight of their fellow Catholics in Mexico and by resentment of their treatment by the Protestant-dominated U.S. military. Today, a plaque in Mexico City marks the site where most of them were executed by other U.S. troops. And Mexicans annually commemorate the Battle of Churubusco, where the soldiers were captured, by listening to a band of bagpipers, which is meant to represent the Mexican battalion that was largely formed by these American defectors and that was named for Saint Patrick, el Batallón de San Patricio.

MEASURING MIGHT

Although Greenberg did not intend to write a military history, her book could have used less biographical detail and more developed comparisons of the war’s opposing armies. In this case, the differences between the two forces were immense.

U.S. troops benefited from major advantages in equipment and training. The U.S. Army’s artillery was far more mobile than that of Mexico’s forces, and American-made rifles were state of the art, whereas Mexico’s guns were relics of the Napoleonic Wars, purchased at a discount on the European market. U.S. officers used advanced training in fields such as engineering to design complex battle plans. And their army’s command included many members of the educated elite.

The Mexican army, in contrast, lacked a sizable professional officer corps, and most of its troops came from the poorest segments of society. Whereas volunteers made up three-quarters of U.S. forces, the majority of the Mexican troops were draftees. In the United States, an officer typically ascended to command through his experience on the battlefield; in Mexico, an officer’s rank often reflected his social position rather than his achievements. Moreover, the United States subordinated military officers to civilian control; in Mexico, the military maneuvered and fought for political power -- consequently, the Mexican military was structured primarily to stage military coups rather than fight foreign invaders.

BACK TO THE BORDER

In February 1848, the two countries signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which Mexico accepted the Rio Grande as its northern border and, in exchange for $15 million, ceded the territories now known as New Mexico and California. Polk wanted to annex Baja California as well, and some called for the annexation of Mexico in its entirety. But Nicholas Trist, a diplomat who represented the American side in the negotiations, explicitly defying Polk’s instructions and then Polk’s orders that he return to Washington, made the final arrangement less harsh. Trist thought Polk’s proposed treaty terms went too far. He believed it was his duty to “protect the people of America from the impossible burden of annexing Mexico.” And most of all, he had seen firsthand the violence inflicted by U.S. soldiers on Mexican civilians, later calling the invasion “a thing for every right-minded American to be ashamed of.” The feelings of Trist, who had intimate knowledge of the war, contrasted sharply with those of the U.S. press. For the editors of The Democratic Review, “the brilliant success of our brave and magnanimous army in Mexico” brought “to mind the victorious struggles of our first armies.”

Meanwhile, Mexicans greeted their loss with profound grief. Lucas Alamán, perhaps the greatest nineteenth-century Mexican historian, had watched the final battles for Mexico City with a spyglass from the roof of his house in the barrio of San Cosme. At the time, he had been at work on the final chapters of his great history of the Mexican struggle for independence. In the aftermath of the war, he confronted the cruel paradox of having completed a history of the independence of Mexico just as it endured a new conquest -- and at the hands of a country that was not even born when the Spanish conquest created Mexico. Alamán believed that his country was doomed to meet the fate of the Mayas, the Toltecs, and the Aztecs; Mexicans seemed “destined to be one of those peoples who once established themselves on this land and then disappeared from the surface of the earth leaving hardly a memory of [their] existence.”

Mexico’s fate was not quite so grim, of course. But the wicked war established the boundaries of the deeply unequal relationship between Mexico and the United States that persists today. Mexico’s defeat still lingers as a scar on the country’s political and popular memory, one that aches in moments as serious as a trade negotiation and as trivial as a soccer game. The combustible nature of Mexican nationalism makes little sense without it.

But in the twenty-first century, both countries have been granted an unexpected opportunity to compensate in part for the past, both practically and symbolically -- and it is the United States that can take the initiative. Today, there are millions of Mexicans living in the United States, legally and illegally -- in essence, a substantial part of Mexico within American borders. Unlike the small number of Mexicans who lived in the territories annexed by the United States through the treaty of 1848, these people are driven to the United States by economic need, and they in turn fulfill U.S. economic needs. Americans cannot afford the luxury of denying their presence. The passage of legislation providing a route to U.S. citizenship for undocumented immigrants would be an excellent way to confront the sins of the past and for Mexico and the United States to mutually make their peace with it.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions