International development has moved beyond charity. Gone are the days when the United States would just spend its seemingly bottomless largess to help less fortunate or vanquished countries, as it did after World War II. International development has reached a new, globally competitive stage, bringing with it enormous strategic and economic implications for the United States in the years ahead.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the global middle class will grow from an estimated 1.8 billion people in 2009 to 4.9 billion in 2030. Nearly all of that growth will occur outside Europe and North America, from Brazil, China, and India to countries in the Middle East, North Africa, and Southeast Asia. Eighty-five percent of the growth will come in the Asia-Pacific region alone. The priorities of those countries will change along with their demographics. With more people escaping poverty, governments’ focus is shifting from meeting basic needs to ensuring longer-term economic prosperity. Instead of handouts, nations are looking for investments to keep their middle classes employed. And more often than not, those investments are for infrastructure that enables and sustains growth.

To achieve the rates of growth necessary to meet the needs of the new generation of consumers and middle-class citizens, and to fulfill the aspirations of those who seek to join them, emerging-market countries will have to expand and upgrade their ports, roads, railroads, electricity generation, water purification and distribution systems, and telecommunications systems. Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos has admitted as much by committing more than $50 billion to infrastructure improvements by 2021 to sustain Colombia’s recent GDP growth. India’s government has acknowledged that it must increase its total infrastructure spending to more than ten percent of GDP by 2017 to maintain its growth-rate targets.

Because much of the investment to build this infrastructure will come from the private sector instead of aid, development has become one of most promising international business opportunities of our time. Nearly $60 trillion in infrastructure investments will be required around the world between now and 2030 just to keep up with projected global GDP growth, according to the McKinsey Global Institute, translating to enormous potential economic windfalls for companies that can design and build that infrastructure. But in countries such as India, local firms lack the capacity and the funding needed to execute many of the projects that the government envisions. U.S. companies can fill this gap.

The benefits of participating in international infrastructure development cannot be measured just in dollars and cents. Given the magnitude of what is at stake -- helping billions escape poverty -- investing in development is also a strategic imperative for the United States. By operating abroad, U.S. companies not only contribute to Americans’ material well-being; they also represent the United States and promote its image overseas. Helping other countries grow by building their roads, ports, and airports boosts U.S. leadership and, in turn, the American brand. Simply put, the United States should not let others build the next Panama Canal.

But U.S. companies are not taking sufficient advantage of the opportunities offered by the new market for infrastructure. Indeed, the Nicaraguan Congress recently authorized a Hong Kong company to build a canal between the Pacific and the Caribbean, at an estimated cost of $40 billion. U.S. firms are generally less experienced and more risk averse than their competitors, and they often face bidding processes and procurement policies that are rigged against them. And making matters worse, U.S. companies at times do not receive the help they need from the American public sector. Yet neither U.S. companies nor the U.S. government need be resigned to failure: there is still time for U.S. firms to get into the game, and Washington can and should do more to support those companies in the global infrastructure market.

KNOW THE COMPETITION

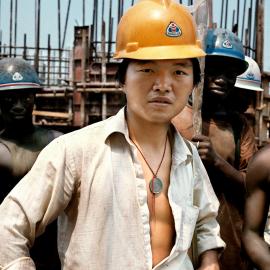

So far, the United States has failed to become a significant player in international infrastructure development. In 2012, the two dozen or so U.S. construction and engineering companies that compete in the field captured barely 14 percent of the revenues earned by international companies outside their home markets. Government officials from Colombia to Indonesia complain that representatives of Brazilian, Chinese, South Korean, and European companies constantly visit and tout their credentials but that months can go by without anyone from a U.S. company coming to their doorsteps. According to International Construction magazine, the construction and engineering company Bechtel was the only U.S. contractor ranked in the world’s top ten construction companies by overall revenue in 2011. That year, French, German, Italian, and Spanish firms accounted for more than half of the overseas revenue generated by international contractors, and European companies represented seven of the top ten transportation developers worldwide, as measured by the number of projects they had under construction or in operation. Chinese firms, meanwhile, may be newcomers, but they are growing fast. Although Chinese contractors’ total market share outside China, according to Engineering News-Record, was only 13.8 percent in 2011, the three biggest construction companies by total revenue in both 2010 and 2011 were Chinese. And all three of those entities are state-owned.

American companies face numerous hurdles and impediments -- many of them self-imposed -- that have left them lagging in this increasingly critical sector. To start with, U.S. firms have been less focused on international markets than their European competitors, which have a longer track record building infrastructure in the developing world. Despite the United States’ geographic proximity and close ties to Latin America and the Caribbean, for example, in 2011, Spanish companies alone received 32 percent of the revenues generated by international contractors in that region. Experience designing and implementing projects in Asia enabled European companies to grab nearly $50 billion in contracts in that region in 2011 -- twice as much as the Chinese did in their own neighborhood. Although U.S. companies sometimes point out that their counterparts can operate free from the constraints of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a U.S. federal law that forbids the bribery of foreign officials, most of the world’s leading infrastructure firms abide by equivalent domestic legislation and hail from countries that have signed the OECD’s Anti-Bribery Convention.

European firms enjoy an advantage in some developing countries partly because of Europe’s colonial history and the resulting cultural ties and familiarity. But they have also been aided by being forced to roam farther afield in search of new opportunities outside their smaller domestic markets. By contrast, the sheer geographic size of the United States has allowed American construction and engineering companies to stay away from unfamiliar markets. U.S. firms looking to expand could find opportunities closer to home, a potentially safer proposition than doing business abroad.

Compounding the problem is the unique nature of the U.S. infrastructure market, which historically has not prepared domestic companies to compete internationally. According to the OECD, the United States has lagged behind Australia and Europe in privatizing critical infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and tunnels. Also, despite the country’s geographic size, American infrastructure projects tend to be local. With the exception of the interstate highway system and the railroads, most U.S. projects are undertaken at the state or municipal level, which means smaller contracts and a bidding process that rewards local contacts and knowledge.

Doing business in the developing world often means dealing with inadequate legal protections and nerve-racking political risk. Most American telecommunications, energy, and water companies that entered Latin American markets in the last 15 years suffered significant losses, left, and show little desire to return. Some, such as ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips in Venezuela, saw their assets nationalized. Others were forced to renegotiate concessions agreed to with host governments after significant investments had already been made. A few in countries such as Argentina even chose to hand projects back to the host countries and take the tax write-offs rather than continue to do business there. This history partly accounts for why many U.S. companies continue to shy away from pursuing large and profitable, but risky, projects abroad.

Making the matter worse is the growing prevalence of infrastructure projects based on a “build-operate-transfer” (BOT) method, which shifts almost all of the projects’ early risks onto the developers. That model, which is not widely used in the United States, makes developers responsible for the costs of completing projects. The BOT model also requires developers, in order to win government contracts, to put together complete packages of construction companies, technical operators, and financers. Although BOT agreements would appear to ensure predictable revenues, in practice they are frequently renegotiated due to delays, cost overruns, or other changes in the operating environment. A World Bank study of 1,000 infrastructure concessions awarded in Latin America and the Caribbean between 1989 and 2000 found that more than 41 percent were renegotiated. According to the researchers, even that figure probably understates the true rate, given that infrastructure contracts typically run for more than 20 years. None of this is likely to give U.S. contractors much comfort about their potential returns on investment.

Faced with such uncertainty, U.S. companies often opt to serve as subcontractors on discrete aspects of overseas projects, thereby lowering their risk and their return -- and the American profile. It is not surprising, then, that foreign governments complain that many U.S. infrastructure companies do not offer complete turnkey packages.

OUT-OF-TOWNERS

Emerging markets often do not present a level playing field: U.S. firms must frequently compete with state-owned or state-aided enterprises. Those favored local competitors can enjoy advantages stemming from formal regulations (such as laws giving them preference) or informal mechanisms (such as contacts with key local players or political pressure to favor domestic production), which makes U.S. companies think twice before participating in lengthy and expensive tender processes.

Consider a 2010 update to Brazil’s procurement law. The measure gave preference to local or foreign firms already operating in Brazil that fulfilled economic stimulus requirements, such as generating employment or contributing to technological development, even if their prices were up to 25 percent higher than competing bids from companies based outside the country. This provision was added to the original law’s implementing regulations, which favored domestic producers and required foreign bidders to incorporate local content to qualify for fiscal benefits. And winning infrastructure contracts in China is no easier: as the State Department’s 2013 “Investment Climate Statement” on China makes clear, China’s often murky regulations allow its government to restrict foreign investment that might compete with state-sanctioned monopolies or other favored domestic firms in key sectors of its economy.

The World Trade Organization has sought to address such inequities through its revised Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA), which requires participating countries to make their public-sector contracting processes transparent. Yet few of the countries with large government-sponsored infrastructure plans are currently parties to the agreement. China, Colombia, India, and Turkey are just observers (although U.S. companies in Colombia do benefit from the recently approved bilateral free-trade agreement). Only Beijing is currently negotiating its accession to the agreement -- and has been since 2007. Brazil is not even an observer.

In addition to facing these structural hurdles, U.S. firms also have trouble getting a fair shot at development funds. Despite a strong U.S. government presence on the boards of development institutions such as the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, U.S. companies do poorly when it comes to winning projects funded by those organizations. Although U.S. contractors receive more funds from the Millennium Challenge Corporation -- a congressionally mandated foreign aid agency intended to fight global poverty -- than any other country’s companies, they had been awarded only about 13 percent, or $800 million, of the total disbursed as of 2012. In an attempt to correct this, the Millennium Challenge Corporation has barred state-owned enterprises from bidding on the development projects that it funds in a select group of poor but well-governed countries. Similarly, World Bank statistics show that Brazil, China, and India receive the bulk of civil-works contracts financed by the bank, although those numbers do not reflect subcontracts that U.S. firms may have obtained. Perhaps because they do not think they will win them, U.S. firms often do not even bid on multilateral bank contracts. When they do, their prices are generally too high. Since entities such as the World Bank and the African Development Bank focus on up-front costs instead of the economic impact over a project’s lifetime, developing-country firms, which can typically offer lower labor costs, usually win out. U.S. companies often have advantages that can result in lower costs over a project’s lifetime, ranging from high-quality workmanship to the ability to complete projects on schedule, but those strengths are easily overlooked in bidding processes focused on design and construction costs rather than maintenance and other long-term needs.

Competing in the international infrastructure sector is made all the more difficult by the fact that U.S. firms cannot count on nearly as much government support as their competitors. American contractors receive a fraction of the export financing that their counterparts in developing countries can expect from their governments. As of the middle of 2011, the financing offered by the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) to their exporters was larger than the combined assistance given to their competitors in the G-7 countries. In 2011, the Brazilian Development Bank, one of the largest development banks in the world, disbursed more than three times as much funding as the World Bank and nearly ten times as much as the Inter-American Development Bank. Almost half of its lending was devoted to infrastructure, but it was restricted to Brazilian legal entities, individuals, and public institutions or Brazilian subsidiaries of foreign companies.

Countries such as Brazil and China do not just give out more loans to local firms; they also offer them better terms. Neither country is a signatory to the OECD’s Export Credits Arrangement, which, among other things, sets the minimum interest rates and maximum repayment terms that participating countries can offer their exporters. Although the arrangement does allow the Export-Import Bank of the United States to match the terms offered by nonsignatory countries, it is often difficult to determine what assistance nonparticipants are offering absent the transparency provided by the OECD agreement.

MADE IN AMERICA

The time is ripe for U.S. firms to step up their game, and U.S. companies can still catch up to their Brazilian, Chinese, and European competitors if they move quickly. They should open their sales pitches by stressing quality over price. Chinese companies, for example, might charge lower prices, but they have a spotty record when it comes to delivering high-quality projects on schedule -- and governments are beginning to notice. Last summer, a Chinese contractor failed to keep a major highway project in Poland within budget and had to abandon it just before Poland hosted the Euro 2012 soccer tournament. Several other Chinese firms quit construction projects in Saudi Arabia in 2012 due to conflicts with the government over standards. According to Saudi regulatory officials, necessary improvements in the quality of the materials used would have put the Chinese companies’ prices near those of their American and European competitors. But American companies must recognize that this advantage will not last, as Chinese and other foreign firms will undoubtedly improve.

At the same time, U.S. companies will have to adapt to the nature of the global infrastructure market, including the trend toward do-it-all approaches to infrastructure development, such as the BOT model. Developing-country governments frequently stress the simplicity of more comprehensive models and wish U.S. companies knew that they prefer “package deal” bids. Global competitors have already recognized this trend. According to a 2011 survey of 161 CEOs of engineering and construction companies by the auditor KPMG, consolidation and competition will take most midsize companies out of the market. If relatively smaller U.S. companies want to compete in an environment that favors large, state-aided contractors offering comprehensive infrastructure schemes, they will need to start thinking bigger and look to partner with companies possessing complementary advantages.

CAPITAL IMPROVEMENTS

American companies cannot get into the infrastructure game alone; Washington will need to help. To be fair, various U.S. departments and agencies already provide support with financing, technical advice, and assistance to mitigate risk and deal with foreign governments during the bidding process. Through the International Trade Administration, the Department of Commerce provides international financing and logistics solutions, trade data and analysis, and assistance with licenses, regulations, and market access and compliance issues. The Overseas Private Investment Corporation offers medium- to long-term funding through direct loans and loan guarantees, together with political risk insurance. The U.S. Export-Import Bank makes available numerous financing options for U.S. companies involved in overseas development. The U.S. Trade and Development Agency provides grant funding to sponsors of overseas projects for activities that support infrastructure development, such as technical assistance, training programs, and early investment analysis and feasibility studies. But even these efforts pale in comparison to those of U.S. competitors.

And it looks like American companies may get even less help in the future, as budgetary pressures have shrunk some export-boosting programs. Facing demands to cut costs, the Department of Commerce, whose mission includes advocating on behalf of U.S. companies trying to win contracts abroad, had to trim its fiscal year 2012 trade-promotion budget request to $350 million -- roughly the same amount it received six years earlier. The cuts have already affected how the Commerce Department does business abroad. Last year, for example, the department shuttered its U.S. Commercial Service’s West Africa office, based in Dakar, Senegal. An office in English-speaking South Africa, thousands of miles away, now covers that region. The U.S. Export-Import Bank also had to fight for its life in Congress last year, despite having made a $700 million profit and having supported U.S. exporters with an unprecedented $35 billion in much-needed financing during the previous fiscal year. All these cutbacks come in the middle of President Barack Obama’s five-year National Export Initiative, which aims to double U.S. exports by 2014 from their 2009 totals.

Even in the face of budget cuts, U.S. commercial agencies must do more to open up opportunities for American companies. Washington can start by providing firms with more market intelligence, taking advantage of the diplomatic missions it has in nearly every country in the world. U.S. Foreign Service officers are privy to a wealth of information about overseas markets that would help American companies in their strategic planning and risk mitigation. Currently, not enough of this intelligence reaches the private sector. The State Department now runs regular conference calls through a program called Direct Line, which puts U.S. businesses in contact with U.S. ambassadors so that they can discuss business opportunities in host countries. The program has been well received and has attracted nearly 4,000 participants. The State Department also plans to unveil soon a “trade leads” website focused on infrastructure. But Washington still needs to keep businesses better informed about the conditions affecting investment abroad: other governments’ procurement plans, changes in economic conditions or priorities, who the key government players are, and who are potential competitors and partners.

Next, the U.S. government needs to improve access to financing. Doing so will require convincing Congress of the economic and strategic importance of more loans for U.S. companies bidding on infrastructure development projects abroad. Financing terms often make or break large infrastructure deals; U.S. lawmakers need to understand that competing with Chinese, South Korean, and European companies, among others, requires giving U.S. firms better access to credit. Instead of debating ways to weaken or eliminate the Export-Import Bank, Congress should be increasing the budget and the lending cap of an institution that regularly earns a profit for U.S. taxpayers while helping boost exports. The same goes for the other government agencies that help level the playing field for U.S. companies abroad.

Washington must also continue pressing Beijing to bring its export credit practices in line with those of the world’s other major economies. Obama’s announcement, following a February 2012 meeting with then Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping, that China and the United States would begin talking about a set of international export credit guidelines that are “consistent with international best practices” was a good start. But the U.S. government needs to ensure that any agreement resulting from those negotiations limits the scope and increases the transparency of the assistance Beijing provides to Chinese exporters.

Because of budget cuts, the Department of Commerce and other U.S. government agencies will need to advocate more efficiently on behalf of U.S. firms. To address the reduction in U.S. Commercial Service personnel, Washington could emulate several European countries and boost its partnership with the American Chambers of Commerce Abroad to provide more advice and advocacy to U.S. companies. Germany’s Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology, for example, works closely with the Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce to promote the country’s exports. Similarly, representatives of the German Trade and Investment Agency, which helps advise foreign companies about investing in Germany, meet with foreign chambers of commerce, thus expanding the reach of the organization and allowing it to promote investment in Germany and share market intelligence with German companies.

BREAKING BARRIERS

None of this will matter, however, if U.S. firms continue to face an uneven playing field in key infrastructure markets. The State Department and the U.S. trade representative must convince major infrastructure consumers, such as Brazil, China, and India, to accede to the GPA. Their doing so would eliminate many of the impediments that keep American firms from securing contracts. Washington will also have to redouble its bilateral and multilateral efforts to eliminate or mitigate the various regulations abroad, such as local content requirements, that place American companies at a disadvantage.

The U.S. government now imposes a two percent tax on foreign contract holders from countries that have not acceded to the GPA. But this measure has not persuaded developing countries to join the agreement, because their companies are not major contractors in the U.S. national infrastructure market. Moreover, the law does not cover contracts with U.S. state and municipal entities, unless they have acceded to the GPA. Thus, more effective approaches are needed to get these government procurement giants to play by rules that do not favor their own companies.

But even convincing large procurers such as Brazil, China, and India to sign on to the GPA will not be enough. The U.S. government should promote the adoption of international procurement principles in every possible venue. Continuing to incorporate those principles in free-trade agreements, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, would help ensure that the United States’ trade partners also adhered to high-standard obligations in line with those of the revised GPA. Not only would this provide U.S. suppliers with increased market access to public procurement and infrastructure markets overseas, but it would also encourage accessions to the GPA by American trade partners that will have already agreed to GPA-consistent obligations in their free-trade agreements.

Finally, Washington must continue to stress that the quality of infrastructure projects built by American firms will often justify their higher costs. The U.S. government should insist that foreign governments and multilateral development banks, such as the World Bank, include stricter quality requirements and total lifetime costs in their project specifications. According to Commerce Department officials and evidence from the field, U.S. firms fare better when such government procurements are assessed based on cost and quality, not simply on which firm comes in with the lowest bid.

The $60 trillion global infrastructure market represents an unprecedented international business opportunity. But if non-U.S. companies build these roads, ports, power stations, and other projects, it will boost the image of the countries they represent at the expense of the United States. Without significant increases in private-industry initiative and government support, U.S. firms risk falling further behind their foreign competitors, or simply being left out of this boom altogether. For the long-term benefit of the American economy and the United States’ strategic position, both the public and the private sector in the United States must recognize the opportunities at hand. Failing to do so would be bad business, and worse policy.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions