My First Trip to China: Scholars, Diplomats, and Journalists Reflect on Their First Encounters With China. Edited by Kin-Ming Liu. East Slope Publishing, 2012, 316 pp. $28.00.

Over the last decade or so, historians and journalists have chipped away -- some with sledgehammers, others with mallets -- at several long-standing myths about China’s past. China wasn’t all darkness and pain before the communist revolution of 1949, and Western efforts to change the country, long portrayed by historians as a tragic dead end, have been far more successful than anyone could have ever dreamed -- to cite just two. The weight of these and other revelations should demand a fundamental reassessment of China’s position in the world, both in the past and going forward. But don’t hold your breath. China scholars and average citizens alike still cling to their own personal notions of the “authentic” China, deeply rooted in the soil of their imaginations.

A good example of this complex comes from My First Trip to China, a collection of 30 vignettes from a veritable who’s who of China experts relating their initial encounters with “the Promised Land,” as one of the contributors describes the country. Disillusion and nostalgia flow through the book like a river. The course of China’s history was supposed to run across exotic and revolutionary terrain. But sadly, many of these authors seem to say, it hasn’t.

One of the fascinating things about My First Trip is how little the latest research into China’s past has changed the views of the contributors. It’s an indication of the tenacity with which many of us China watchers cling to our beliefs -- no matter how outdated -- about the place. And so the book forces one to ask why so many have harbored such overwrought expectations for China and its revolution, why so many still hold on to those ideas, and why so many react with such vehemence -- or incredulity -- when they are proved wrong.

REVISIONISM WITH CHINESE CHARACTERISTICS

Aided by the obvious fact that China matters very much to global politics and economics now, recent historians have marshaled a powerful case that China mattered in the past, too. Starting in the late 1990s, scholars began to skewer the notions that imperial China was never an expansionist power (it conquered huge chunks of Central Asia, after all) and that it shunned trade with the outside world. New histories of China’s nineteenth-century economy and the anti–Qing dynasty Taiping Rebellion of 1850–64 have placed China at the center of the world. Fluctuations in China’s consumer demand worried the British parliament as much as the spiraling price of cotton from the American South. The Taiping Rebellion inspired Karl Marx and American missionaries alike. China was indeed the Middle Kingdom, not because it was floating out there in isolated Oriental splendor but because it was a kingdom in the middle of the world.

Another flawed idea that contemporary writers have deflated is the notion that life in China before the communist revolution was a nightmare of serfdom and oppression. The Nanjing decade of 1927–37, when the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek ruled, is now understood as a period when the economy expanded, civil society was strengthened, and modern science and education spread throughout the country. Chiang himself no longer comes across as the cartoonish, incompetent baddie depicted in Barbara Tuchman’s influential 1970 tome, Stilwell and the American Experience in China. He is now seen as a leader, albeit a flawed one, whose armies fought and died for China. Meanwhile, Tuchman’s demigod, U.S. General “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, who commanded troops alongside Chiang during World War II, has been restored to his status as a mortal, with scholars questioning his leadership and strategy.

Mao Zedong, the subject of several new biographies, has similarly shed the legendary veneer applied to him by Edgar Snow, whose 1937 Red Star Over China was the first work in any language to mythologize the Great Helmsman. Research in Soviet archives has revealed that Mao was thoroughly in the pocket of Stalin and has cast doubt on the claim, long accepted by China experts in the United States, that Mao’s forces fought hard against the Japanese during World War II. For the most part, it seems, Mao kept his powder dry, built his army, and waited for Chiang’s forces to exhaust themselves against the Japanese. And as for the progressive chestnut that in the mid-1940s, Mao pondered positioning himself between Washington and Moscow? That idea now appears to have belonged to the “New Democracy” plan, worked out between Mao and Stalin, which successfully bamboozled a slew of U.S. diplomats into believing that Mao was, as one claimed at the time, a mere “agrarian reformer” and not, as it turned out, a Stalin acolyte.

On other fronts, most historians have stopped describing China’s interaction with the Western world with such tired terms as “cultural imperialism.” New scholarship has recognized the extent to which both foreigners and Western-educated Chinese supplied the keys to the opening up of the Chinese mind. Realizing how important Westerners are to China’s transformation today, historians now acknowledge the central role they played in the past. Americans, Britons, Germans, Japanese, and Russians served as advisers, models, teachers, and guides. American missionaries brought education, science, and Western medicine; the British exported modern administrative techniques; the Germans taught the Nationalist Chinese about modern warfare. Even China’s postal service was imported from abroad, from France. The image of a timeless, unchanging China, the passive victim of imperialist depredations, simply does not comport with the facts. “Chinese who embraced the new -- when given a chance to do so -- always far outnumbered those who did not,” writes Odd Arne Westad in Restless Empire, a magisterial work on China’s ties to the Western world published last year.

Westad’s observation should ring true to anyone who has traveled to China in the past 30 years. But the new vision of the country it presents also makes a lot of people uneasy. Westerners are not used to thinking of China as an ever-changing giant that has always, except for an anomalous three-decade detour under Mao, been of the world rather than apart from it. They are troubled to discover a history that is more contested than the somewhat monochromatic story line they have held on to for the past several decades. They are not comfortable with a China that was always more familiar than they wanted it to be.

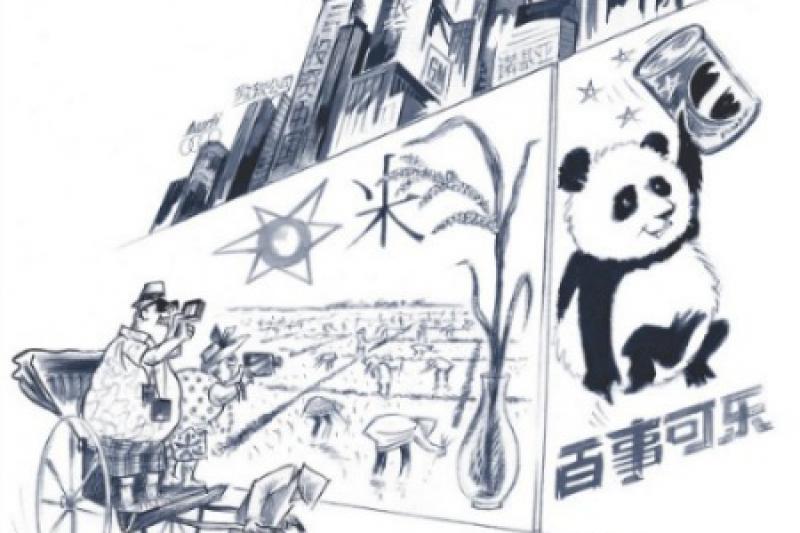

This vexation is not just the domain of bookworms and old China hands. My wife runs a travel company in China and marvels at the discomfort that her American counterparts feel toward this different China. She once suggested that one of them advise her clients to visit a Starbucks in our neighborhood, Sanlitun, one of the hipper corners of Beijing, and people-watch as eager shoppers stream through the cavernous Apple store next door. “Why should I send my clients to see that?” the agent asked. “That’s not the ‘real’ China.” Everyone wants his own personal rickshaw and rice paddy.

I, too, walk around with my own private China. I think most Chinese want to live as Americans do and aspire to the power and freedom of the United States. But then again, I could be completely wrong.

RED-COLORED GLASSES

A nostalgia for something that might never have existed courses through My First Trip. No one describes it better than Orville Schell, the author of the book’s foreword and one of the greatest writers on China of his generation. “Just as the last geographically unexplored pockets of our planet were vanishing and leaving us without our accustomed fix of exotica and romance,” Schell writes, the Cold War served up Mao’s China, “a surprising new surrogate form of the forbidden.” Schell paints a China that is breathlessly feminine -- “strangely alluring,” with “haughty detachment” and “mesmerizing impenetrability and unpossessability.” He compares cadging entry into the Celestial Kingdom with the entreaties of a dogged lover. In the years before China opened up, he and the rest of his fellow China watchers, he writes, resembled “a group of forlorn Swanns in love. And like Marcel Proust’s anti-hero’s unrequited passion for Odette, our infatuation with China was only made more ardent by the hopelessness of any possibility of attention, much less consummation.”

Then the visas started trickling out, and those who were invited in embraced another view of China: that of an exclusive club. For many of the writers featured in My First Trip, China of the early 1980s was perfect in its own way; they could fantasize that it was unsullied by westernization but still sense that it was on the brink of epochal change. “It seemed to me an ideal period,” writes the urban studies scholar Porus Olpadwala, another contributor to the book, who visited China with a delegation of city planners in 1985. China was “the best of two worlds, with the worst of socialism slowly being discarded and capital’s travails still some distance away.” Nowadays, of course, the country’s doors have blown wide open; the once-private China is not so private anymore.

And yet many Westerners still hold on to nostalgia for the goals of China’s revolution and harbor sympathy for the Communist Party. Take another contributor, Lois Wheeler Snow, the second wife of Edgar Snow, the American writer who trafficked in the notion that the communist revolution was inevitable and that Mao’s dictatorship was necessary to free China from the chains of its Confucian past. Lois Wheeler Snow visited China in 1970 with her ailing husband. Mao invited the couple to the dais at the Gate of Heavenly Peace, overlooking Tiananmen Square, and had a picture of them all taken and then published in the People’s Daily (an unheeded message to Washington that Beijing was seeking warmer ties). She recalls standing so close to Mao that she “could have touched the mole on his face,” as the chairman waved to his adoring masses, “just like . . . the Beatles, Sinatra, Michael Jackson.”

Snow seems willing to forgive party central for the Great Leap Forward (an estimated 40 million dead) and the Cultural Revolution (a million or so dead and the ruination of millions more lives), but not the 1989 massacre at Tiananmen Square (in which an estimated 800 people died). “If crop yields were sometimes exaggerated, women’s roles somewhat overstated or statistics unproven, sturdy stone and brick houses, reclaimed green fields and orchards gave evidence that hard work had made life better than ever before,” she writes of life under Mao. But after 1989, she explains, “I broke with the Chinese leadership. . . . I no longer visit.”

Why was Tiananmen the last straw? The answer might lie in Snow’s discomfort with the market-oriented path China has taken and with her unmet expectation that the Chinese would somehow leverage communism to free themselves from the West’s cycle of worldly desires. Before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms of the 1980s, Snow writes, quoting her husband, China pursued policies “for the communal good, not for private gain.” Although those policies resulted in the deaths of millions, she is saddened to see that today China and the United States are “engaged in capitalist competition.” Once again, an American finds that the Chinese resemble Americans more than she is comfortable with.

It is tempting to direct such people to take in China’s 2013 summer blockbusters Tiny Times 1 and 2. These films tell the story of four Shanghai coeds who swap rich lovers as if they were handbags -- a kind of Sex and the City meets The Devil Wears Prada, as Sheila Melvin put it in The New York Times. Perhaps it would also help to point out that more than 50 percent of Chinese now live in cities, up from 19 percent in the 1970s. Rice paddies and egalitarianism beware: this is the real China. Tiny Times 3 is set to come out next year.

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

Americans of all political stripes have long harbored outsized expectations for China -- and those high hopes have made disappointment inevitable. The China scholars Jonathan Mirsky, Steven Mosher, and Perry Link all contributed moving pieces to My First Trip. All came away from their initial interactions with the country deflated. Mirsky and Link had both demonstrated against the Vietnam War and were highly critical of U.S. policies in Asia. But their first visits to the mainland, in the early 1970s, brought them face-to-face with Chinese minders who specialized in showing them Potemkin villages, Potemkin workers, even Potemkin subways. When the visitors dared to poke their heads behind the curtain, they were harangued. “In the years since 1973 I have learned much, much more about how wrong I was in the late 1960s to take Mao Zedong’s ‘socialism’ at face value,” confesses Link, who later taught East Asian studies at Princeton. “I am a bit puzzled that others among my leftist-student friends from the 1960s sometimes seem reluctant to face this obvious fact.”

Mosher, one of the first American graduate students to do fieldwork in China, arrived in 1979 in a village in the Pearl River Delta. He brought with him a faith in Mao’s socialism, but disillusion set in fast; the squalid life of rural Guangdong Province disabused him of the notion that China was a workers’ and peasants’ paradise. Then, he witnessed the unveiling of China’s one-child policy, which played out in a high tide of forced abortions and sterilizations; he saw the operations firsthand. Once a fellow traveler, Mosher quickly became a sworn enemy of China’s population polices. “The sense that all of this was truly wicked grew,” he writes.

But why did he expect anything better? Olpadwala provides a clue. When he first visited China, in 1985, Olpadwala came from India and was impressed. Compared with the rest of the developing world, China was doing well: it was clean, people had jobs, and there were no slums. Olpadwala found himself disagreeing with the Western members of his delegation. “Where I saw almost everyone housed, they noticed the drabness. . . . Where I saw everyone clothed, they observed sartorial monotony; where I saw shops stocked with basics, they remarked on the lack of variety.” Olpadwala’s comment gets to the heart of Americans’ views of China as opposed to, say, their perspective on India, which Americans rarely compare to more advanced countries. Americans have always expected more from China, and even today, they hold it to a higher standard.

There is another, more practical, less romantic strain in how Americans have looked at China, one illustrated in the contributions of William Overholt, at the time a banker, and Ezra Vogel, a professor emeritus of East Asian studies at Harvard. Although the pragmatic view of China sometimes degenerates into boosterism, it also helps explain why many Americans have stood with China -- no matter its governments -- over the decades.

Overholt arrived in 1982 and, thanks to connections he had made at the time of China’s first mission to the United Nations, was squired around the country by a colonel in the People’s Liberation Army. Overholt’s Chinese friends peppered him with questions: How does one cash a check in New York? How might they finagle $1 million in interest from a pre–World War II American checking account? Overholt understood then what would not appear plausible to most Westerners until a decade later: that China was on the cusp of an economic revolution like those that had just taken place in South Korea and Taiwan, except with a population almost 20 times as large as the two others’ combined. The results would shake the world.

Vogel, who was a member of the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars, which lobbied against the war in Vietnam, first visited in 1973. But he was less radical, had a less rosy view of communist China, and was more pro-American than many of his comrades, he notes, partially because his father, a Jew, had succeeded in the United States, while other family members died in the Holocaust. Vogel saw the same China as his colleagues did: people were poor, frightened, and cowed by Maoist orthodoxy. Yet, he explains, using language that American Sinophiles of all stripes have employed for centuries, he “wanted Chinese leaders to succeed, to make life better for their people, and wanted to help bridge the gap between China and America.” His first visit continues to serve as a bellwether that allows him to defend his personal notion of China, “to tell those Westerners who later complained about limitations [on free expression] . . . how much change had taken place.”

THE SEARCH GOES ON

The Chinese, of course, have their own overblown expectations -- of the West, specifically the United States, a fact often overlooked by Western scholars somehow embarrassed by the power of Americans to do good. Two of the contributors to My First Trip make clear that the U.S.-Chinese relationship has long been a two-way street. Morton Abramowitz visited China in 1978 as a U.S. Defense Department official, accompanying President Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, whose goal was to fashion a de facto alliance with Beijing against the Soviet Union. Abramowitz’s mission was to brief the Chinese on Soviet capabilities on their borders -- a huge show of faith from the United States. Abramowitz recalls Brzezinski joking with their hosts, pointing north to the Soviet border and saying, “Out there is the Russian bear and I am the bear tamer.” While Abramowitz shared sensitive American intelligence, his counterpart from the People’s Liberation Army soaked it in; then, he shook Abramowitz’s hand and left without a question. “I was impressed,” Abramowitz writes, with “how well China played a weak hand.”

Weaker still was China’s hand in 1972, when the legal expert Jerome Cohen met with Premier Zhou Enlai along with other American scholars to push the idea of cultural and educational exchange. After cajoling the aging Chinese leader to open up his country, Cohen took a bathroom break with John Fairbank, the legendary China scholar. Suggesting that perhaps the pair had squeezed Zhou a bit too hard, Fairbank gazed at Cohen from across his urinal and quipped, “The missionary spirit dies hard!”

The reality is that the Chinese were desperate for Abramowitz’s briefing and for the exchanges offered by Fairbank and Cohen, which would ultimately help propel China again into the modern world. Those exchanges were indeed born from “the missionary spirit” -- the profoundly American desire to help China and to shape its future. Often belittled, that desire -- leavened by a healthy dose of Yankee self-interest -- continues to drive the relationship between the two Pacific powers today. No wonder everyone in China is talking about “the Chinese dream.”

And what of the Chinese themselves? Beijing still invests a huge amount of energy -- and now capital -- in molding Western perceptions of China. (Estimates for the build-out of China’s media operations overseas hover well over $200 million.) But the results, like those of the early propaganda tours narrated in My First Trip, are less than spectacular. For a while in the late 1990s, it looked as if China was ready to embrace a more sophisticated approach. It offered experts background briefings of substance and allowed more significant and relaxed interactions with opinion leaders and members of the press. But that ended during the reign of Hu Jintao. What has replaced it, curiously enough, seems inspired by the “fickle mistress” of Schell’s China: a government that pretends not to care what foreigners think. And so the search for the real China goes on.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions