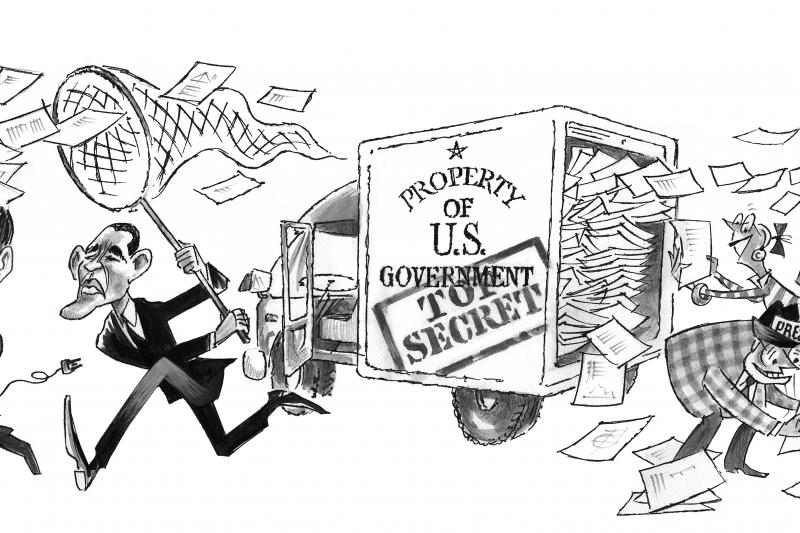

Secrets and Leaks: The Dilemma of State Secrecy. By Rahul Sagar. Princeton University Press, 2013, 304 pp. $35.00.

The U.S. government commands few capabilities more potent than its power to declare information secret. Even when the judiciary and Congress exercise their checks-and-balances powers over the executive branch, the American secrecy machine still finds a way to shunt aside substantive discussions about a host of programs and policies.

With little or no public input, the U.S. government has kidnapped suspected terrorists, established secret prisons, performed “enhanced” interrogations, tortured prisoners, and carried out targeted killings. After the former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden pilfered hundreds of thousands of documents from the NSA’s computers and released them to journalists last summer, the public learned of additional and potentially dodgy secret government programs: warrantless wiretaps, the weakening of public encryption software, the collection and warehousing of metadata from phones and e-mail accounts, and the interception of raw Internet communications.

The secrecy machine was originally designed to keep the United States’ foes at bay. But in the process, it has transformed itself into an invisible state within a state. Forever discovering new frontiers to patrol, as the Snowden files indicate, the machine molts its skin each season to grow ever larger and more powerful, encountering little resistance from the courts or Congress.

In his new book, Secrets and Leaks, the Princeton political scientist Rahul Sagar ably documents this growth in secrecy and the problems it poses, excavating from his thorough research a concise history of concealment and revelation from the Revolutionary War to the present. Atop this scholarship, he adds legal analysis and an attempt to map a regulatory framework that will keep the country secure, make the government accountable, and still preserve Americans’ civil liberties. Yet in overestimating the damage leaks cause and underestimating how hard it will be to stop them, Sagar arrives at recommendations that are ultimately too impractical and too restrictive.

SWORN TO SECRECY

Sagar asks, when is it legitimate for an official to disclose secrets? His answer is both conventional and brave -- because he must know how many readers will find examples that call his reasoning into question. Unauthorized disclosures of classified material should remain illegal, he writes, because no one official can know with any certainty which disclosures will ultimately serve the public interest. Having made the case for keeping the laws against leaking secrets intact, Sagar then sets five conditions a disclosure must meet before officials can disregard the laws: the disclosure must reveal real wrongdoing or the abuse of public authority, it must be based on evidence rather than hearsay, it must not threaten public safety disproportionately, it must be limited in scale and scope as much as possible, and the leaker must unmask himself and take his lumps to prove that he made the disclosure in good faith and not to gain advantage for himself or his allies.

The Snowden affair happened too late for Sagar to include it in Secrets and Leaks beyond a throwaway footnote, but it makes for an obvious and interesting test of Sagar’s framework. Snowden’s unilateral disclosures do not come close to clearing Sagar’s standard for legalization: as an NSA worker bee, Snowden was in no position to balance the public-interest repercussions of his acts. Nor do they clear Sagar’s first condition for justifiability: although the mass surveillance Snowden revealed may have come as a disconcerting shock to many of his fellow citizens, it might not have been illegal.

As James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, reiterated in late October, “We believe we have been lawful.” Given what the applicable laws say and the way they have been secretly interpreted and executed (quite liberally), Clapper might very well be right. The NSA’s surreptitious collection, storage, and analysis of terabytes of personal data was sanctioned by the president, the members of Congress charged with oversight, and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, a special court established in 1978 to field warrants from the NSA and the FBI. The NSA’s surveillance program may be wrong and repugnant to the values enshrined in the Fourth Amendment, which bars unreasonable search and seizure, but it cannot be called wrongdoing or an abuse of power. It is not in the same galaxy as, say, President Richard Nixon’s domestic surveillance programs or the Watergate break-ins, which Nixon tried to pass off as part of a national security operation.

Snowden’s leaks easily clear Sagar’s second condition: you can’t call hundreds of thousands of copies of secret NSA documents hearsay. But Sagar’s third condition for legitimate leaking -- that a disclosure not threaten public safety disproportionately -- is so vague that it vaporizes on the page as you read it. That criticism won’t surprise Sagar, who seeks a good, not a perfect, regulatory framework for controlling leaks. As he concedes, measuring the threat to public safety has historically been a crapshoot: he cites the 1979 case in which the U.S. government obtained a temporary restraining order to prevent the left-wing magazine The Progressive from publishing an article that detailed a design for a hydrogen bomb. (The magazine’s recipe was concocted from public and declassified sources, but under the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, such information was deemed “born secret.”) In his ruling, Judge Robert Warren found that The Progressive’s article, if published, “would irreparably harm the national security of the United States.” But the case became a moot issue after another publication printed similar information. Needless to say, Warren’s prediction of irreparable harm never materialized.

The government issued similar dire warnings in 1971, when Erwin Griswold, the solicitor general, argued the Pentagon Papers case before the Supreme Court. Leaked by the military analyst Daniel Ellsberg, the papers detailed the U.S. government’s covert escalation of the war in Vietnam. Their publication, Griswold insisted, would deeply harm national security. But in 1989, he recanted that claim in a Washington Post op-ed. “I have never seen any trace of a threat to the national security from the publication,” he wrote. “Indeed, I have never seen it even suggested that there was such an actual threat.” Griswold still defended limited classification powers that would protect military plans as they are being made, negotiations with foreign governments, and details about weapons, but no more. “It quickly becomes apparent to any person who has considerable experience with classified material that there is massive over-classification and that the principal concern of the classifiers is not with national security, but rather with governmental embarrassment of one sort or another,” he wrote.

If neither the publication of H-bomb secrets nor the release of the Pentagon Papers irreparably harmed national security, then what secrets gone feral will? Clearly, such secrets exist. The leaking of troop placements, battle plans, communications codes, the status of the nation’s code-cracking efforts, the capabilities of some weapons systems, or details about ongoing military operations can damage national security and even result in the deaths of U.S. military personnel. But springing those sorts of secrets is of more interest to spies and hostile foreign nations than to whistleblowers and the press.

As for the valid criticism that Snowden blunted the surveillance cutlery the NSA uses to cut into al Qaeda’s communications by exposing the agency’s methods, without a doubt, the leaks have taught terrorist organizations new techniques of surveillance avoidance. But that criticism doesn’t land a knockout blow: according to the White House review panel convened last year to examine the NSA’s surveillance practices, the bulk collection of phone records has stopped precisely zero attacks. “There has been no instance in which NSA could say with confidence that the outcome would have been different” had the metadata-collection program not existed, its report states in a footnote. So yes, Snowden gave the terrorists something, but he gave much, much more to the hundreds of millions of Americans whose data was being collected and stored without their consent.

As critics of overclassification maintain, most of the real estate devoted to state secrets is occupied by the mundane, the innocuous, and the obvious. U.S. drone strikes against suspected terrorist targets, common knowledge to all news consumers, were technically secret until President Barack Obama finally acknowledged the program in April 2012. In fact, as Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan argued in his 1998 book, Secrecy: The American Experience, excessive secrecy can actually harm national security by pre-venting policymakers from learning valuable information required to make informed decisions. He gave the example of President Harry Truman, whom the U.S. Army and the FBI did not inform of the “Venona decryptions,” intercepted communications documenting ongoing Soviet espionage in the United States, because they thought his White House was too leaky.

On condition four, that a disclosure be as limited in scale as possible, Snowden strikes out there, too, but primarily in terms of the volume of secrets stolen (since only a small portion of those have been publicly disseminated so far). According to Alan Rusbridger, the editor of The Guardian, his newspaper has published only one percent of the 58,000 files it obtained from Snowden. And on condition five, although Snowden has unmasked himself, his actions can hardly be characterized as civil disobedience, considering that he ran away to Russia rather than submit himself for judgment and possible punishment within the system.

That the Snowden leaks fare so poorly according to Sagar’s criteria, however, shows just how restrictive and establishmentarian Sagar’s framework actually is and why a less rigid regulatory setup than Sagar proposes is desirable. After all, in December, a federal judge declared some of the practices that Snowden exposed to be unconstitutional, and nearly half the members of the House of Representatives have gone on record with what amounts to a soft endorsement of Snowden’s revelations by voting for a bill defunding some of the activities revealed.

Sagar’s framework has problems handling not just venti-sized leaks such as Snowden’s but tall ones, too. Elected officials will continue to exploit the pent-up power contained in minor secrets by trickling them out to the press because they know prosecutors will not charge them and their colleagues will not censure them. Indeed, such secrets exist in ever-growing surplus. The most recent government report finds that more than 95 million “derivative classification decisions” were made in FY 2012 -- a derivative classification being a document, correspondence, or publication that is classified because it contains or paraphrases information previously classified. Given that 1.4 million individuals, including 483,000 contractors like Snowden, currently hold top-secret clearance over this giant aquifer of secrets, Americans should be grateful there isn’t more leaking.

The routinization of leaking should be apparent to anybody who reads newspapers. Nearly every day, reporters grant anonymity to “current and former government officials” (as the telling passage usually goes), who then spill government secrets with permission from their superiors. The meat on many authorized disclosures is no less sacrosanct than the meat on unauthorized disclosures, but because these leaks serve the state’s interests, they are tolerated. Government officials have been passing secrets to reporters in hopes of advancing the state’s interests or to protect other, more important secrets since before the national security beat was invented. They do so “not to subvert policy but to explain it, to defend it and to execute it,” as Steven Aftergood, the director of the Project on Government Secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists, has written. “Though it may seem counterintuitive (and may in fact violate formal procedures),” he adds, “sometimes officials will even reveal currently classified information to enhance security.”

THE LEAKY CAULDRON

If Sagar’s proposal for regulating leaking is not the right solution, then what is? Nobody is naive enough to believe that the spooks can police themselves: as Ryan Lizza put it in The New Yorker in December, “The history of the intelligence community . . . reveals a willingness to violate the spirit and the letter of the law, even with oversight.” Sagar devotes a chapter to why the regulation of secrecy can’t be turned over to the courts -- they lack the expertise and the training to parse secrets, and they are supposed to be open institutions, doing their business in public. Nor can Americans expect Congress to do much better than the executive branch, he argues in another entire chapter. Congress can serve as a watchdog, but there is no reason to think it “will behave any more responsibly than the president,” especially when it knows that outsiders will not be able to second-guess its decisions.

That leaves whistleblowers and the press to hold the president accountable for his handling of secrets. Sagar shuns this option. Although he approves of leaks that prevent abuses of power, he believes (along with many others in and around government) that journalists lack the necessary understanding of the big picture to responsibly pass unauthorized disclosures on to the public.

I disagree (but then, as a journalist, I would), because from where I sit, it seems the press has actually been quite conscientious in this regard -- for example, in its reporting on the files stolen by the army private now known as Chelsea Manning. In January 2011, my Reuters colleague Mark Hosenball, a national security reporter, cited internal U.S. government reviews that assert that the massive leaks of diplomatic cables by Manning “caused only limited damage to U.S. interests abroad” and “made public few if any real intelligence secrets.” As with the publication of the Pentagon Papers, the leaks created more embarrassment than damage.

As for the Snowden leaks, it’s too early for journalists and others to discount the damage they may have done to U.S. national security. But rare is the leaker whose output unites almost half the House of Representatives, as well as the top Internet companies -- Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Apple, Twitter, LinkedIn, Yahoo, and AOL -- which issued a joint statement in early December protesting the government spying revealed by journalists working with Snowden.

At the end of his book, Sagar laments that the dilemma of state secrecy may not be solvable. But after reading his impeccable scholarship, a different, more plausible conclusion emerges: that there is no pressing dilemma or, rather, that the First Amendment has resolved the dilemma by giving freedom of the press primacy over secrecy laws. Yes, reporters can be compelled to surrender the identities of their confidential sources to the courts, but as Sagar observes, “no reporter, editor, or publisher has ever been prosecuted for publishing classified information.” Even in cases in which journalists have disclosed communications intelligence, an explicit violation of federal law, prosecutors have still declined to file charges. According to Sagar, the press gets off easy because the government doesn’t want to fight with the people who buy ink by the barrel or because it doesn’t want to reveal additional secrets in court to make its case. More likely, however, it is because the government fears that should the First Amendment come into direct collision with secrecy laws, it will trump and weaken them.

Sagar finds despair in the eternal and “unruly contest” between the president and the press over secrecy. He’d like to see the press practice better “self-censorship,” especially when leaks reveal kinds of law breaking that don’t constitute genuine abuses of government power. But he promptly acknowledges the fragility of such self-censorship: leakers turned down by one publication are likely to continue to peddle their information until they find a taker. Presidents, he writes, could boost their own credibility and reduce the urge to leak by governing in a more open fashion, refraining from making self-serving leaks of their own, and abiding by the rule of law. But again, that sort of self-discipline does not come easy. The political advantages gained by dispensing official leaks are too enticing for most presidents. Even when presidents resist the temptation, other parts of the bureaucracy often plunder the growing stash of leaks for institutional gain.

Making secrets and managing them have always been a great source of political power, and the closer politicians get to this power, the more enamored of it they become. Case in point: as a member of the U.S. Senate, Obama co-sponsored or supported several failed measures that would have reduced the secrecy cloaking various NSA surveillance programs, as ProPublica detailed last summer. After becoming president, Obama quelled his reformist tendencies, and today, he’s the custodian and protector of those programs.

“Where an excess of power prevails,” to steal a phrase from James Madison, almost no leader can resist going too far in accomplishing his goals if the opportunity presents itself. And if you are the president of the United States, opportunity knocks loudly several times a day. The lesson of Snowden, a lesson Sagar points to but refuses to embrace, is that the United States’ muddled system of leaks by lawbreakers to the press is an irreplaceable last resort.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions