Back in 2009, during his heavily promoted Cairo speech on American relations with the Muslim world, U.S. President Barack Obama noted, in passing, that “in the middle of the Cold War, the United States played a role in the overthrow of a democratically elected Iranian government.” Obama was referring to the 1953 coup that toppled Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq and consolidated the rule of the shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Obama would go on to remind his audience that Iran had also committed its share of misdeeds against Americans. But he clearly intended his allusion to Washington’s role in the coup as a concession -- a public acknowledgment that the United States shared some of the blame for its long-simmering conflict with the Islamic Republic.

Yet there was a supreme irony to Obama’s concession. The history of the U.S. role in Iran’s 1953 coup may be “well known,” as the president declared in his speech, but it is not well founded. On the contrary, it rests heavily on two related myths: that machinations by the CIA were the most important factor in Mosaddeq’s downfall and that Iran’s brief democratic interlude was spoiled primarily by American and British meddling. For decades, historians, journalists, and pundits have promoted these myths, injecting them not just into the political discourse but also into popular culture: most recently, Argo, a Hollywood thriller that won the 2013 Academy Award for Best Picture, suggested that Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution was a belated response to an injustice perpetrated by the United States a quarter century earlier. That version of events has also been promoted by Iran’s theocratic leaders, who have exploited it to stoke anti-Americanism and to obscure the fact that the clergy itself played a major role in toppling Mosaddeq.

In reality, the CIA’s impact on the events of 1953 was ultimately insignificant. Regardless of anything the United States did or did not do, Mosaddeq was bound to fall and the shah was bound to retain his throne and expand his power. Yet the narrative of American culpability has become so entrenched that it now shapes how many Americans understand the history of U.S.-Iranian relations and influences how American leaders think about Iran. In reaching out to the Islamic Republic, the United States has cast itself as a sinner expiating its previous transgressions. This has allowed the Iranian theocracy, which has abused history in a thousand ways, to claim the moral high ground, giving it an unearned advantage over Washington and the West, even in situations that have nothing to do with 1953 and in which Iran’s behavior is the sole cause of the conflict, such as the negotiations over the Iranian nuclear program.

All of this makes developing a better and more accurate understanding of the real U.S. role in Iran’s past critically important. It’s far more than a matter of correcting the history books. Getting things right would help the United States develop a less self-defeating approach to the Islamic Republic today and would encourage Iranians -- especially the country’s clerical elite -- to claim ownership of their past.

HONEST BROKERS

In the years following World War II, Iran was a devastated country, recovering from famine and poverty brought on by the war. It was also a wealthy country, whose ample oil reserves fueled the engines of the British Empire. But Iran’s government didn’t control that oil: the wheel was held by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, whose majority shareholder happened to be the British government. By the early 1950s, as assertive nationalism swept the developing world, many Iranians were beginning to see this colonial-era arrangement as an unjust, undignified anachronism.

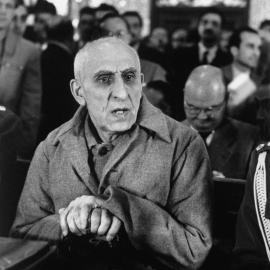

So strong was the desire to take back control of Iran’s national resources that it united the country’s liberal reformers, its intelligentsia, elements of its clerical establishment, and its middle-class professionals into a coherent political movement. At the center of that movement stood Mosaddeq, an upper-class lawyer who had been involved in Iranian politics from a young age, serving in various ministries and as a member of parliament. Toward the end of World War II, Mosaddeq reemerged on the political scene as a champion of Iranian anticolonialism and nationalism and managed to draw together many disparate elements into his political party, the National Front. Mosaddeq was not a revolutionary; he was respectful of the traditions of his social class and supported the idea of constitutional monarchy. But he also sought a more modern and more democratic Iran, and in addition to the nationalization of Iran’s oil, his party’s agenda called for improved public education, freedom of the press, judicial reforms, and a more representative government.

In April 1951, the Iranian parliament voted to appoint Mosaddeq prime minister. In a clever move, Mosaddeq insisted that he would not assume the office unless the parliament also approved an act he had proposed that would nationalize the Iranian oil industry. Mosaddeq got his way in a unanimous vote, and the easily intimidated shah capitulated to the parliament’s demands. Iran now entered a new and more dangerous crisis.

The United Kingdom, a declining empire struggling to adjust to its diminished influence, saw the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company as a crucial source of energy and profit, as well as a symbol of what little imperial prestige the country had managed to cling to through the end of World War II. So London responded to the nationalization with fury. It warned European companies doing business in Iran to pull out or face retribution, and the still potent British navy began interdicting ships carrying Iranian oil on the grounds that they were transporting stolen cargo. These moves -- coupled with the fact that the Western oil giants, which were siding with London, owned nearly all the tankers then in existence -- managed to effectively blockade Iran’s petroleum exports. By 1952, Iran’s Abadan refinery, the largest in the world at the time, was grinding to a halt.

From the outset of the nationalization crisis, U.S. President Harry Truman had sought to settle the dispute. The close ties between the United States and the United Kingdom did not lead Washington to reflexively side with its ally. Truman had already demonstrated some regard for Iran’s autonomy and national interests. In 1946, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin had sought to seize Iran’s northern provinces by refusing to withdraw Soviet forces that were deployed there during the war. Truman objected, insisting on maintaining Iran’s territorial integrity even if it meant rupturing the already frayed U.S. alliance with the Soviets; Stalin backed off. Similarly, when it came to the fight to control Iran’s oil, the Americans played the role of an honest broker. Truman dispatched a number of envoys to Tehran who urged the British to acknowledge the legitimacy of the parliament’s nationalization act while also pressing the Iranians to offer fair compensation for expropriated British assets.

In the meantime, Washington continued providing economic assistance to Iran, as it had ever since the war began -- assistance that helped ease the pain of the British oil blockade. And the Americans dissuaded the British from using military force to compel Iran to relent, as well as rejecting British pleas for a joint covert operation to topple Mosaddeq.

But Truman’s mediation fell short, owing more to Mosaddeq’s intransigence than any American missteps. Mosaddeq, it seemed, considered no economic price too high to protect Iran’s autonomy and national pride. In due course, Mosaddeq and his allies rejected every U.S. proposal that preserved any degree of British participation in Iran’s oil sector. It turned out that defining Iran’s oil interests in existential terms had handcuffed the prime minister: any compromise was tantamount to forfeiting the country’s sovereignty.

TRUE COLORS

By 1952, the conflict had brought Iran’s economy to the verge of collapse. Tehran had failed to find ways to get its oil around the British embargo and, deprived of its key source of revenue, was facing mounting budget deficits and having difficulty meeting its payroll. Washington began to fear that through his standoff with the British, Mosaddeq had allowed the economy to deteriorate so badly that his continued rule would pave the way for Tudeh, Iran’s communist party, to challenge him and take power.

And indeed, as the dispute dragged on, Mosaddeq was faced with rising dissent at home. The cause of nationalization was still popular, but the public was growing weary of the prime minister’s intransigence and his refusal to accept various compromise arrangements. The prime minister dealt with the chorus of criticism by expanding his mandate through constitutionally dubious means, demanding special powers from the parliament and seeking to take charge of the armed forces and the Ministry of War, both of which had long been under the shah’s control.

Even before the Western intelligence services devised their plots, Mosaddeq’s conduct had already alienated his own coalition partners. The intelligentsia and Iran’s professional syndicates began chafing under the prime minister’s growing authoritarianism. Mosaddeq’s base of support within the middle classes, alarmed at the economy’s continued decline, began looking for an alternative and drifted toward the royalist opposition, as did the officer corps, which had suffered numerous purges.

Mosaddeq’s supporters among the clergy, who had endorsed the nationalization campaign and had even encouraged the shah to oppose the United Kingdom’s imperial designs, now began to reconsider. The clergy had never been completely comfortable with Mosaddeq’s penchant for modernization and had come to miss the deference they received from the conservative and insecure shah. Watching Iran’s economy collapse and fearing, like Washington, that the crisis could lead to a communist takeover, religious leaders such as Ayatollah Abul-Qasim Kashani began to subtly shift their allegiances. (Since the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Iran’s theocratic rulers have attempted to obscure the inconvenient fact that, at a critical juncture, the mullahs sided with the shah.)

The crisis finally came to a head in February 1953, when the royal court, fed up with Mosaddeq’s attempts to undermine the monarchy, suddenly announced that the shah intended to leave the country for unspecified medical reasons, knowing that the public would interpret the move as a signal of the shah’s displeasure with Mosaddeq. The gambit worked, and news of the monarch’s planned departure caused a serious confrontation between Mosaddeq and his growing list of detractors. Kashani joined with disgruntled military officers and purged politicians and publicly implored the shah to stay. Protests engulfed Tehran and many provincial cities, and crowds even attempted to ransack Mosaddeq’s residence. Sensing the public mood, the shah canceled his trip.

This episode is particularly important, because it demonstrated the depth of authentic Iranian opposition to Mosaddeq; there is no evidence that the protests were engineered by the CIA. The demonstrations also helped the anti-Mosaddeq coalition solidify. Indeed, it would be this same coalition, with greater support from the armed forces, that would spearhead Mosaddeq’s ouster six months later.

THE PLOT THICKENS

The events of February made an impression on a frustrated Washington establishment. The CIA reported to U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower, who had inherited the Iranian dilemma when he took office a month earlier, that “the institution of the Crown may have more popular backing than we expected.” Secretary of State John Foster Dulles cabled the U.S. embassy in Tehran that “there appears to be [a] substantial and relatively courageous opposition group both within and outside [the] Majlis [Iran’s parliament]. We gather Army Chiefs and many civilians [are] still loyal to the Shah and would act if he gave them positive leadership, or even if he merely acquiesced in [a] move to install [a] new government.”

After the protests, the Majlis became the main seat of anti-Mosaddeq agitation. Since Mosaddeq’s ascension to the premiership, his seemingly arbitrary decision-making, his inability to end the oil crisis, and the narrowing of his circle to a few trusted aides had gradually alienated many parliamentarians. In response, the prime minister decided to eliminate the threat by simply dissolving the Majlis. Doing so required executing a ploy of dubious legality, however: on July 14, all the National Front deputies loyal to Mosaddeq resigned their posts at once, depriving the chamber of the necessary quorum to function. Mosaddeq then called for a national referendum to decide the fate of the paralyzed legislature. But this was hardly a good-faith, democratic gesture; the plebiscite was marred by boycotts, voting irregularities, and mob violence, and the results surprised no one: Mosaddeq’s proposal to dissolve parliament was approved by 99 percent of the voters. Mosaddeq won his rigged election, but the move cost him what remained of his tattered legitimacy.

Meanwhile, Mosaddeq seemed determined to do everything he could to confirm Washington’s worst fears about him. The prime minister thought that he could use U.S. concerns about the potential for increased Soviet influence in Iran to secure greater assistance from Washington. During a meeting in January, Mosaddeq had warned Loy Henderson, the U.S. ambassador, that unless the United States provided him with sufficient financial aid, “there will be [a] revolution in Iran in 30 days.” Mosaddeq also threatened to sell oil to Eastern bloc countries and to reach out to Moscow for aid if Washington didn’t come through. These threats and entreaties reached a climax in June, when Mosaddeq wrote Eisenhower directly to plead for increased U.S. economic assistance, insisting that if it were not given right away, “any steps that might be taken tomorrow to compensate for the negligence of today might well be too late.” Eisenhower took nearly a month to respond and then firmly told Iran’s prime minister that the only path out of his predicament was to settle the oil dispute with the United Kingdom.

By that point, however, Washington was already actively considering a plan the British had developed to push Mosaddeq aside. The British intelligence agency, MI6, had identified and reached out to a network of anti-Mosaddeq figures who would be willing to take action against the prime minster with covert American and British support. Among them was General Fazlollah Zahedi, a well-connected officer who had previously served in Mosaddeq’s cabinet but had left after becoming disillusioned with the prime minister’s leadership and had immersed himself in opposition politics. Given its history of interference in Iran, the British government also boasted an array of intelligence sources, including members of parliament and journalists, whom it had subsidized and cultivated. London could also count on a number of influential bazaar merchants who, in turn, had at their disposal thugs willing to instigate violent street protests.

The CIA took a rather dim view of these British agents, believing that they were “far overstated and oversold.” Nevertheless, by May, the agency had embraced the basic outlines of a British plan to engineer the overthrow of Mosaddeq. The U.S. embassy in Tehran was also on board: in a cable to Washington, Henderson assured the Eisenhower administration that “most Iranian politicians friendly to the West would welcome secret American intervention which would assist them in attaining their individual or group political ambitions.”

The joint U.S.-British plot for covert action was code-named TPAJAX. Zahedi emerged as the linchpin of the plan, as the Americans and the British saw him as Mosaddeq’s most formidable rival. The plot called for the CIA and MI6 to launch a propaganda campaign aimed at raising doubts about Mosaddeq, paying journalists to write stories critical of the prime minister, charging that he was corrupt, power hungry, and even of Jewish descent -- a crude attempt to exploit anti-Semitic prejudices, which the Western intelligence agencies wrongly believed were common in Iran at the time. Meanwhile, a network of Iranian operatives working for the Americans and the British would organize demonstrations and protests and encourage street gangs and tribal leaders to provoke their followers into committing acts of violence against state institutions. All this was supposed to further inflame the already unstable situation in the country and thus pave the way for the shah to dismiss Mosaddeq.

Indeed, the shah would be the plot’s central actor, since he retained the loyalty of the armed forces and only he had the authority to dismiss Mosaddeq. “If the Shah were to give the word, probably more than 99% of the officers would comply with his orders with a sense of relief and with the hope of attaining a state of stability,” a U.S. military attaché reported from Tehran in the spring of 1953.

IF AT FIRST YOU DON'T SUCCEED

On July 11, Eisenhower approved the plan, and the CIA and MI6 went to work. The Western intelligence agencies certainly found fertile ground for their machinations, as the turmoil sweeping Iran had already seriously compromised Mosaddeq’s standing. It appeared that all that was left to do was for the shah to officially dismiss the prime minister.

But enlisting the Iranian monarch proved more difficult than the Americans and the British had initially anticipated. On the surface, the shah seemed receptive to the plot, as he distrusted and even disdained his prime minister. But he was also clearly reluctant to do anything to further destabilize his country. The shah was a tentative man by nature and required much reassurance before embarking on a risky course. The CIA did manage to persuade his twin sister, Princess Ashraf, to press its case with her brother, however. Also urging the shah to act were General Norman Schwarzkopf, Sr., a U.S. military officer who had trained Iran’s police force and enjoyed a great deal of influence in the country, and Kermit Roosevelt, Jr., a CIA official who had helped devise the plot. Finally, on August 13, 1953, the shah signed a royal decree dismissing Mosaddeq and appointing Zahedi as the new prime minister.

Zahedi and his supporters wanted to make sure that Mosaddeq received the decree in person and thus waited for more than two days before sending the shah’s imperial guards to deliver the order to the prime minister’s residence at a time when Zahedi was certain Mosaddeq would be there. By that time, however, someone had tipped Mosaddeq off. He refused to accept the order and instead had his security detail arrest the men the shah had sent. Zahedi went into hiding, and the shah fled the country, going first to Iraq and then to Italy. The plot, it seemed, had failed. Mosaddeq took to the airwaves, claiming that he had disarmed a coup, while neglecting to mention that the shah had dismissed him from office. Indeed, it was Mosaddeq, not the shah or his foreign backers, who failed to abide by Iran’s constitution.

After the apparent failure of the coup, a mood of resignation descended on Washington and London. According to an internal review prepared by the CIA in 1954, after Mosaddeq’s refusal to follow the shah’s order, the U.S. Department of State determined that the operation had been “tried and failed,” and the official British position was equally glum: “We must regret that we cannot consider going on fighting.” General Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s confidant and wartime chief of staff, who was now serving as undersecretary of state, had the unenviable task of informing the president. In a note to Eisenhower, Smith wrote:

The move failed. . . . Actually, it was a counter-coup, as the Shah acted within his constitutional power in signing the [decree] replacing Mosaddeq. The old boy wouldn’t accept this and arrested the messenger and everybody else involved that he could get his hands on. We now have to take a whole new look at the Iranian situation and probably have to snuggle up to Mosaddeq if we’re going to save anything there.

The White House, the leadership of the CIA, and the U.S. embassy in Tehran all shared the view that the plot had failed and that it was time to move on. It seems that some operatives in the CIA station in Tehran thought there was still a chance that Zahedi could succeed, if he asserted himself. The station might even have maintained some contact with Zahedi; it’s not clear whether it did or not. What is clear is that by that point, the attempt to salvage the coup became very much an Iranian initiative.

A TRAGIC FIGURE

In the aftermath of the failed coup, chaos reigned in Tehran and political fortunes shifted quickly. The Tudeh Party felt that its time had finally come, and its members poured into the streets, waving red flags and destroying symbols of the monarchy. The more radical members of the National Front, such as Foreign Minister Hossein Fatemi, also joined the fray with their own denunciations of the shah. An editorial in Bakhtar-e Emruz, a newspaper Fatemi controlled, castigated the royal court as “a brothel, a filthy, corrupt place”; another editorial in the same newspaper warned the shah that the nation “is thirsty for revenge and wants to see you on the gallows.” Such talk alarmed military officers and clerics and also outraged many ordinary Iranians who still respected the monarchy. Mosaddeq himself did not call for disbanding the monarchy. Despite his attempts to expand his powers at the shah’s expense, Mosaddeq remained loyal to his vision of a constitutional monarchy.

The shah issued a statement from exile declaring that he had not abdicated the throne and stressing the unconstitutionality of Mosaddeq’s claim to power. Meanwhile, Zahedi and his coconspirators continued their resistance. Zahedi reached out to armed military units in the capital and in the provinces that remained loyal to the shah and told their commanders to prepare for mobilization. Zahedi also sought to widely broadcast the shah’s decree dismissing Mosaddeq and appointing Zahedi himself as prime minister, and the CIA station in Tehran appears to have helped distribute the message through both domestic and foreign media.

The efforts to publicize the shah’s decree and Mosaddeq’s studied silence are instructive. Many accounts of the coup, including Roosevelt’s, cast the shah as an unpopular and illegitimate ruler who maintained the throne only with the connivance of foreigners. But if that were the case, then Zahedi and his allies would not have worked so hard to try to publicize the shah’s preferences. The fact that they did suggests that the shah still enjoyed a great deal of public and institutional support, at least in the immediate aftermath of Mosaddeq’s countercoup; indeed, the news of the shah’s departure provoked uprisings throughout the country.

These demonstrations did not fundamentally alter the views of U.S. representatives in Iran. As Henderson later recalled, he initially did not take the turmoil very seriously and cabled the State Department that “it would probably have little significance.” Momentum soon built within Iran, however. The clergy stepped into the fray, with mullahs inveighing against Mosaddeq and the National Front. Kashani and other major religious figures urged their supporters to take to the streets. Unlike some of the demonstrations that had taken place earlier in the summer, these protests were not the work of the CIA’s and MI6’s clients. A surprised official at the U.S. embassy reported that the crowds “appeared to be led and directed by civilians rather than military. Participants not of hoodlum type, customarily predominant in recent demonstrations in Tehran. They seemed to come from all classes of people including workers, clerks, shopkeepers, students, et cetera.” A CIA assessment noted that “the flight of [the] Shah brought home to the populace in a dramatic way how far Mosaddeq had gone, and galvanized the people into an irate pro-Shah force.”

Mosaddeq was determined to halt the revolutionary surge and commanded the military to restore order. Instead, many soldiers joined in the demonstrations, as chants of “Long live the shah!” echoed in the capital. On August 19, the army chief of staff, General Taqi Riahi, who had stayed loyal to Mosaddeq until then, telephoned the prime minister to confess that he had lost control of many of his troops and of the capital city. Royalist military units took over Tehran’s main radio station and several important government ministries. Seeing his options narrowing, Mosaddeq went into hiding in a neighbor’s house. But the prime minister was too much of a creature of the establishment to remain on the run for long, and he soon turned himself in. A few months later, Mosaddeq was convicted of treason, for which the mandatory punishment was execution. However, given his age, his long-standing service to the country, and his role in nationalizing Iran’s oil industry, the sentence was commuted to three years in prison. In practice, he would go on to serve a life sentence, spending the remaining 14 years of his life confined to his native village.

Mosaddeq was a principled politician with deep reverence for Iran’s institutions and constitutional order. He had spent his entire public life defending the rule of law and the separation of powers. But the pressures of governing during a crisis accentuated troubling aspects of his character. His need for popular acclaim blinded him to compromises that could have resolved the oil conflict with the United Kingdom and thus protected Iran’s economy. Worse, by 1953, Mosaddeq -- the constitutional parliamentarian and champion of democratic reform -- had turned into a populist demagogue: rigging referendums, intimidating his rivals, disbanding parliament, and demanding special powers.

Popular lore gets two things right: Mosaddeq was indeed a tragic figure, and a victim. But his tragedy was that he couldn’t find a way out of a predicament that he himself was largely responsible for creating. And more than anyone else, he was a victim of himself.

THE MYTH OF U.S. FINGERPRINTS

Since 1953, and especially since the 1979 Islamic Revolution that toppled the shah, the truth about the coup has been obscured by self-serving narratives concocted by Americans and Iranians alike. The Islamic Republic has done much to propagate the notion that the coup and the conspiracy against Mosaddeq demonstrated an implacable American hostility to Iran. The theocratic revolutionaries have been assisted in this distortion by American accounts that grossly exaggerate the significance of the U.S. role in pushing Mosaddeq from power. Chief among these is the version that appears in Roosevelt’s self-aggrandizing 1979 book, Countercoup: The Struggle for the Control of Iran. In his Orientalist rendition, Roosevelt landed in Tehran with a few bags of cash and easily manipulated the benighted Iranians into carrying out Washington’s schemes.

Contrary to Roosevelt’s account, the documentary record reveals that the Eisenhower administration was hardly in control and was in fact surprised by the way events played out. On the eve of the shah’s triumph, Henderson reported in a cable to Washington that the real cause of the coup’s success was that “most armed forces and great numbers [of] Iranian civilians [are] inherently loyal to [the] Shah whom they have been taught to believe is [a] symbol of national unity as well as of [the] stability of the country.” As Iran underwent its titanic internal struggle, even the CIA seemed to be aware that its own machinations had proved relatively unimportant. On August 21, Charles Cabell, the agency’s acting director, reported to Eisenhower that “an unexpectedly strong upsurge of popular and military reaction to Prime Minister Mosaddeq’s Government has resulted, according to late dispatches from Tehran, in the virtual occupation of that city by forces proclaiming their loyalty to the Shah and his appointed Prime Minister Zahedi.”

In addition to overstating the American and British hand in orchestrating Mosaddeq’s downfall and the shah’s restoration, the conventional narrative of the coup neglects the fact that the shah was still popular in the early 1950s. He had not yet become the megalomaniac of the 1970s, but was still a young, hesitant monarch deferential to Iran’s elder statesmen and grand ayatollahs and respectful of the limits of his powers.

But the mythological version of the events of 1953 has persisted, partly because since the Islamic Revolution, making the United States out to be the villain has served the interests of Iran’s leaders. Another reason for the myth’s survival is that in the aftermath of the debacle in Vietnam and in the wake of congressional investigations during the mid-1970s that revealed the CIA’s involvement in covert attempts to foment coups overseas, many Americans began to question the integrity of their institutions and the motives of their government; it hardly seemed far-fetched to assume that the CIA had been the main force behind the coup in Iran.

Whatever the reason for the persistence of the mythology about 1953, it is long past time for the Americans and the Iranians to move beyond it. As Washington and Tehran struggle to end their protracted enmity, it would help greatly if the United States no longer felt the need to keep implicitly apologizing for its role in Mosaddeq’s ouster. As for the Islamic Republic, at a moment when it is dealing with internal divisions and uncertainties about its future, it would likewise help for it to abandon its outdated notions of victimhood and domination by foreigners and acknowledge that it was Iranians themselves who were the principal protagonists in one of the most important turning points in their country’s history.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions