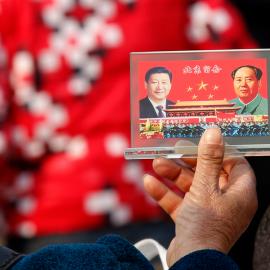

Chinese President Xi Jinping has articulated a simple but powerful vision: the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. It is a patriotic call to arms, drawing inspiration from the glories of China’s imperial past and the ideals of its socialist present to promote political unity at home and influence abroad. After just two years in office, Xi has advanced himself as a transformative leader, adopting an agenda that proposes to reform, if not revolutionize, political and economic relations not only within China but also with the rest of the world.

Underlying Xi’s vision is a growing sense of urgency. Xi assumed power at a moment when China, despite its economic success, was politically adrift. The Chinese Communist Party, plagued by corruption and lacking a compelling ideology, had lost credibility among the public, and social unrest was on the rise. The Chinese economy, still growing at an impressive clip, had begun to show signs of strain and uncertainty. And on the international front, despite its position as a global economic power, China was punching well below its weight. Beijing had failed to respond effectively to the crises in Libya and Syria and had stood by as political change rocked two of its closest partners, Myanmar (also known as Burma) and North Korea. To many observers, it appeared as though China had no overarching foreign policy strategy.

Xi has reacted to this sense of malaise with a power grab—for himself, for the Communist Party, and for China. He has rejected the communist tradition of collective leadership, instead establishing himself as the paramount leader within a tightly centralized political system. At home, his proposed economic reforms will bolster the role of the market but nonetheless allow the state to retain significant control. Abroad, Xi has sought to elevate China by expanding trade and investment, creating new international institutions, and strengthening the military. His vision contains an implicit fear: that an open door to Western political and economic ideas will undermine the power of the Chinese state.

If successful, Xi’s reforms could yield a corruption-free, politically cohesive, and economically powerful one-party state with global reach: a Singapore on steroids. But there is no guarantee that the reforms will be as transformative as Xi hopes. His policies have created deep pockets of domestic discontent and provoked an international backlash. To silence dissent, Xi has launched a political crackdown, alienating many of the talented and resourceful Chinese citizens his reforms are intended to encourage. His tentative economic steps have raised questions about the country’s prospects for continued growth. And his winner-take-all mentality has undermined his efforts to become a global leader.

The United States and the rest of the world cannot afford to wait and see how his reforms play out. The United States should be ready to embrace some of Xi’s initiatives as opportunities for international collaboration while treating others as worrisome trends that must be stopped before they are solidified.

A DOMESTIC CRACKDOWN

Xi’s vision for a rejuvenated China rests above all on his ability to realize his particular brand of political reform: consolidating personal power by creating new institutions, silencing political opposition, and legitimizing his leadership and the Communist Party’s power in the eyes of the Chinese people. Since taking office, Xi has moved quickly to amass political power and to become, within the Chinese leadership, not first among equals but simply first. He serves as head of the Communist Party and the Central Military Commission, the two traditional pillars of Chinese party leadership, as well as the head of leading groups on the economy, military reform, cybersecurity, Taiwan, and foreign affairs and a commission on national security. Unlike previous presidents, who have let their premiers act as the state’s authority on the economy, Xi has assumed that role for himself. He has also taken a highly personal command of the Chinese military: this past spring, he received public proclamations of allegiance from 53 senior military officials. According to one former general, such pledges have been made only three times previously in Chinese history.

In his bid to consolidate power, Xi has also sought to eliminate alternative political voices, particularly on China’s once lively Internet. The government has detained, arrested, or publicly humiliated popular bloggers such as the billionaire businessmen Pan Shiyi and Charles Xue. Such commentators, with tens of millions of followers on social media, used to routinely discuss issues ranging from environmental pollution to censorship to child trafficking. Although they have not been completely silenced, they no longer stray into sensitive political territory. Indeed, Pan, a central figure in the campaign to force the Chinese government to improve Beijing’s air quality, was compelled to criticize himself on national television in 2013. Afterward, he took to Weibo, a popular Chinese microblogging service, to warn a fellow real estate billionaire against criticizing the government’s program of economic reform: “Careful, or you might be arrested.”

Under Xi, Beijing has also issued a raft of new Internet regulations. One law threatens punishment of up to three years in prison for posting anything that the authorities consider to be a “rumor,” if the post is either read by more than 5,000 people or forwarded over 500 times. Under these stringent new laws, Chinese citizens have been arrested for posting theories about the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370. Over one four-month period, Beijing suspended, deleted, or sanctioned more than 100,000 accounts on Weibo for violating one of the seven broadly defined “bottom lines” that represent the limits of permissible expression. These restrictions produced a 70 percent drop in posts on Weibo from March 2012 to December 2013, according to a study of 1.6 million Weibo users commissioned by The Telegraph. And when Chinese netizens found alternative ways of communicating, for example, by using the group instant-messaging platform WeChat, government censors followed them. In August 2014, Beijing issued new instant-messaging regulations that required users to register with their real names, restricted the sharing of political news, and enforced a code of conduct. Unsurprisingly, in its 2013 ranking of Internet freedom around the world, the U.S.-based nonprofit Freedom House ranked China 58 out of 60 countries—tied with Cuba. Only Iran ranked lower.

In his efforts to promote ideological unity, Xi has also labeled ideas from abroad that challenge China’s political system as unpatriotic and even dangerous. Along these lines, Beijing has banned academic research and teaching on seven topics: universal values, civil society, citizens’ rights, freedom of the press, mistakes made by the Communist Party, the privileges of capitalism, and the independence of the judiciary. This past summer, a party official publicly attacked the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a government research institution, for having been “infiltrated by foreign forces.” This attack was met with mockery among prominent Chinese intellectuals outside the academy, including the economist Mao Yushi, the law professor He Weifang, and the writer Liu Yiming. Still, the accusations will likely have a chilling effect on scholarly research and international collaboration.

This crackdown might undermine the very political cohesiveness Xi seeks. Residents of Hong Kong and Macao, who have traditionally enjoyed more political freedom than those on the mainland, have watched Xi’s moves with growing unease; many have called for democratic reform. In raucously democratic Taiwan, Xi’s repressive tendencies are unlikely to help promote reunification with the mainland. And in the ethnically divided region of Xinjiang, Beijing’s restrictive political and cultural policies have resulted in violent protests.

Even within China’s political and economic upper class, many have expressed concern over Xi’s political tightening and are seeking a foothold overseas. According to the China-based Hurun Report, 85 percent of those with assets of more than $1 million want their children to be educated abroad, and more than 65 percent of Chinese citizens with assets of $1.6 million or more have emigrated or plan to do so. The flight of China’s elites has become not only a political embarrassment but also a significant setback for Beijing’s efforts to lure back home top scientists and scholars who have moved abroad in past decades.

A MORAL AUTHORITY?

The centerpiece of Xi’s political reforms is his effort to restore the moral authority of the Communist Party. He has argued that failing to address the party’s endemic corruption could lead to the demise of not only the party but also the Chinese state. Under the close supervision of Wang Qishan, a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, tackling official corruption has become Xi’s signature issue. Previous Chinese leaders have carried out anticorruption campaigns, but Xi has brought new energy and seriousness to the cause: limiting funds for official banquets, cars, and meals; pursuing well-known figures in the media, the government, the military, and the private sector; and dramatically increasing the number of corruption cases brought for official review. In 2013, the party punished more than 182,000 officials for corruption, 50,000 more than the annual average for the previous five years. Two scandals that broke this past spring indicate the scale of the campaign. In the first, federal authorities arrested a lieutenant general in the Chinese military for selling hundreds of positions in the armed forces, sometimes for extraordinary sums; the price to become a major general, for example, reached $4.8 million. In the second, Beijing began investigating more than 500 members of the regional government in Hunan Province for participating in an $18 million vote-buying ring.

Xi’s anticorruption crusade represents just one part of his larger plan to reclaim the Communist Party’s moral authority. He has also announced reforms that address some of Chinese society’s most pressing concerns. With Xi at the helm, the Chinese leadership has launched a campaign to improve the country’s air quality; reformed the one-child policy; revised the hukou system of residency permits, which ties a citizen’s housing, health care, and education to his official residence and tends to favor urban over rural residents; and shut down the system of “reeducation through labor” camps, which allowed the government to detain people without cause. The government has also announced plans to make the legal system more transparent and to rid it of meddling by local officials.

Despite the impressive pace and scope of Xi’s reform initiatives, it remains unclear whether they represent the beginning of longer-term change, or if they are merely superficial measures designed to buy the short-term goodwill of the people. Either way, some of his reforms have provoked fierce opposition. According to the Financial Times, former Chinese leaders Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao have both warned Xi to rein in his anticorruption campaign, and Xi himself has conceded that his efforts have met with significant resistance. The campaign has also incurred real economic costs. According to a report by Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Chinese GDP could fall this year by as much as 1.5 percentage points as a result of declining sales of luxury goods and services, as officials are increasingly concerned that lavish parties, political favor-buying, and expensive purchases will invite unwanted attention. (Of course, many Chinese are still buying; they are just doing so abroad.) And even those who support the goal of fighting corruption have questioned Xi’s methods. Premier Li Keqiang, for example, called for greater transparency and public accountability in the government’s anticorruption campaign in early 2014; his remarks, however, were quickly deleted from websites.

Xi’s stance on corruption may also pose a risk to his personal and political standing: his family ranks among the wealthiest of the Chinese leadership, and according to The New York Times, Xi has told relatives to shed their assets, reducing his vulnerability to attack. Moreover, he has resisted calls for greater transparency, arresting activists who have pushed for officials to reveal their assets and punishing Western media outlets that have investigated Chinese leaders.

KEEPING CONTROL

As Xi strives to consolidate political control and restore the Communist Party’s legitimacy, he must also find ways to stir more growth in China’s economy. Broadly speaking, his objectives include transforming China from the world’s manufacturing center to its innovation hub, rebalancing the Chinese economy by prioritizing consumption over investment, and expanding the space for private enterprise. Xi’s plans include both institutional and policy reforms. He has slated the tax system, for example, for a significant overhaul: local revenues will come from a broad range of taxes instead of primarily from land sales, which led to corruption and social unrest. In addition, the central government, which traditionally has received roughly half the national tax revenue while paying for just one-third of the expenditures for social welfare, will increase the funding it provides for social services, relieving some of the burden on local governments. Scores of additional policy initiatives are also in trial phases, including encouraging private investment in state-owned enterprises and lowering the compensation of their executives, establishing private banks to direct capital to small and medium-sized businesses, and shortening the length of time it takes for new businesses to secure administrative approvals.

Yet as details of Xi’s economic plan unfold, it has become clear that despite his emphasis on the free market, the state will retain control over much of the economy. Reforming the way in which state-owned enterprises are governed will not undermine the dominant role of the Communist Party in these companies’ decision-making; Xi has kept in place significant barriers to foreign investment; and even as the government pledges a shift away from investment-led growth, its stimulus efforts continue, contributing to growing levels of local debt. Indeed, according to the Global Times, a Chinese newspaper, the increase in the value of outstanding nonperforming loans in the first six months of 2014 exceeded the value of new nonperforming loans for all of 2013.

Moreover, Xi has infused his economic agenda with the same nationalist—even xenophobic—sentiment that permeates his political agenda. His aggressive anticorruption and antimonopoly campaigns have targeted multinational corporations making products that include powdered milk, medical supplies, pharmaceuticals, and auto parts. In July 2013, in fact, China’s National Development and Reform Commission brought together representatives from 30 multinational companies in an attempt to force them to admit to wrongdoing. At times, Beijing appears to be deliberately undermining foreign goods and service providers: the state-controlled media pay a great deal of attention to alleged wrongdoing at multinational companies while remaining relatively quiet about similar problems at Chinese firms.

Like his anticorruption campaign, Xi’s investigation of foreign companies raises questions about the underlying intent. In a widely publicized debate broadcast by Chinese state television between the head of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China and an official from the National Development and Reform Commission, the European official forced his Chinese counterpart to defend the seeming disparities between the Chinese government’s treatment of foreign and domestic companies. Eventually, the Chinese official appeared to yield, saying that China’s antimonopoly procedure was a procedure “with Chinese characteristics.”

The early promise of Xi’s overhaul thus remains unrealized. A 31-page scorecard of Chinese economic reform, published in June 2014 by the U.S.-China Business Council, contains dozens of unfulfilled mandates. It deems just three of Xi’s policy initiatives successes: reducing the time it takes to register new businesses, allowing multinational corporations to use Chinese currency to expand their business, and reforming the hukou system. Tackling deeper reforms, however, may require a jolt to the system, such as the collapse of the housing market. For now, Xi may well be his own worst enemy: calls for market dominance are no match for his desire to retain economic control.

WAKING THE LION

Xi’s efforts to transform politics and economics at home have been matched by equally dramatic moves to establish China as a global power. The roots of Xi’s foreign policy, however, predate his presidency. The Chinese leadership began publicly discussing China’s rise as a world power in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, when many Chinese analysts argued that the United States had begun an inevitable decline that would leave room for China at the top of the global pecking order. In a speech in Paris in March 2014, Xi recalled Napoleon’s ruminations on China: “Napoleon said that China is a sleeping lion, and when she wakes, the world will shake.” The Chinese lion, Xi assured his audience, “has already awakened, but this is a peaceful, pleasant, and civilized lion.” Yet some of Xi’s actions belie his comforting words. He has replaced the decades-old mantra of the former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping—“Hide brightness, cherish obscurity”—with a far more expansive and muscular foreign policy.

For Xi, all roads lead to Beijing, figuratively and literally. He has revived the ancient concept of the Silk Road—which connected the Chinese empire to Central Asia, the Middle East, and even Europe—by proposing a vast network of railroads, pipelines, highways, and canals to follow the contours of the old route. The infrastructure, which Xi expects Chinese banks and companies to finance and build, would allow for more trade between China and much of the rest of the world. Beijing has also considered building a roughly 8,100-mile high-speed intercontinental railroad that would connect China to Canada, Russia, and the United States through the Bering Strait. Even the Arctic has become China’s backyard: Chinese scholars describe their country as a “near-Arctic” state.

Along with new infrastructure, Xi also wants to establish new institutions to support China’s position as a regional and global leader. He has helped create a new development bank, operated by the BRICS countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—to challenge the primacy of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. And he has advanced the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which could enable China to become the leading financer of regional development. These two efforts signal Xi’s desire to capitalize on frustrations with the United States’ unwillingness to make international economic organizations more representative of developing countries.

Xi has also promoted new regional security initiatives. In addition to the already existing Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a Chinese-led security institution that includes Russia and four Central Asian states, Xi wants to build a new Asia-Pacific security structure that would exclude the United States. Speaking at a conference in May 2014, Xi underscored the point: “It is for the people of Asia to run the affairs of Asia, solve the problems of Asia, and uphold the security of Asia.”

Xi’s predilection for a muscular regional policy became evident well before his presidency. In 2010, Xi chaired the leading group responsible for the country’s South China Sea policy, which broadened its definition of China’s core interests to include its expansive claims to maritime territory in the South China Sea. Since then, he has used everything from the Chinese navy to fishing boats to try to secure these claims—claims disputed by other nations bordering the sea. In May 2014, conflict between China and Vietnam erupted when the China National Petroleum Corporation moved an oil rig into a disputed area in the South China Sea; tensions remained high until China withdrew the rig in mid-July. To help enforce China’s claims to the East China Sea, Xi has declared an “air defense identification zone” over part of it, overlapping with those established by Japan and South Korea. He has also announced regional fishing regulations. None of China’s neighbors has recognized any of these steps as legitimate. But Beijing has even redrawn the map of China embossed on Chinese passports to incorporate areas under dispute with India, as well as with countries in Southeast Asia, provoking a political firestorm.

These maneuvers have stoked nationalist sentiments at home and equally virulent nationalism abroad. New, similarly nationalist leaders in India and Japan have expressed concern over Xi’s policies and taken measures to raise their countries’ own security profiles. Indeed, during his campaign for the Indian prime ministership in early 2014, Narendra Modi criticized China’s expansionist tendencies, and he and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe have since upgraded their countries’ defense and security ties. Several new regional security efforts are under way that exclude Beijing (as well as Washington). For example, India has been training some Southeast Asian navies, including those of Myanmar and Vietnam, and many of the region’s militaries—including those of Australia, India, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, and South Korea—have planned joint defense exercises.

A VIGOROUS RESPONSE

For the United States and much of the rest of the world, the awakening of Xi’s China provokes two different reactions: excitement, on the one hand, about what a stronger, less corrupt China could achieve, and significant concern, on the other hand, over the challenges an authoritarian, militaristic China might pose to the U.S.-backed liberal order.

On the plus side, Beijing’s plans for a new Silk Road hinge on political stability in the Middle East; that might provide Beijing with an incentive to work with Washington to secure peace in the region. Similarly, Chinese companies’ growing interest in investing abroad might give Washington greater leverage as it pushes forward a bilateral investment treaty with Beijing. The United States should also encourage China’s participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a major regional free-trade agreement under negotiation. Just as China’s negotiations to join the World Trade Organization in the 1990s prompted Chinese economic reformers to advance change at home, negotiations to join the TPP might do the same today.

In addition, although China already has a significant stake in the international system, the United States must work to keep China in the fold. For example, the U.S. Congress should ratify proposed changes to the International Monetary Fund’s internal voting system that would grant China and other developing countries a larger say in the fund’s management and thereby reduce Beijing’s determination to establish competing groups.

On the minus side, Xi’s nationalist rhetoric and assertive military posture pose a direct challenge to U.S. interests in the region and call for a vigorous response. Washington’s “rebalance,” or “pivot,” to Asia represents more than simply a response to China’s more assertive behavior. It also reflects the United States’ most closely held foreign policy values: freedom of the seas, the air, and space; free trade; the rule of law; and basic human rights. Without a strong pivot, the United States’ role as a regional power will diminish, and Washington will be denied the benefits of deeper engagement with many of the world’s most dynamic economies. The United States should therefore back up the pivot with a strong military presence in the Asia-Pacific to deter or counter Chinese aggression; reach consensus and then ratify the TPP; and bolster U.S. programs that support democratic institutions and civil society in such places as Cambodia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Vietnam, where democracy is nascent but growing.

At the same time, Washington should realize that Xi may not be successful in transforming China in precisely the ways he has articulated. He has set out his vision, but pressures from both inside and outside China will shape the country’s path forward in unexpected ways. Some commodity-rich countries have balked at dealing with Chinese firms, troubled by the their weak record of social responsibility, which has forced Beijing to explore new ways of doing business. China’s neighbors, alarmed by Beijing’s swagger, have begun to form new security relationships. Even prominent foreign policy experts within China, such as Peking University’s Wang Jisi and the retired ambassador Wu Jianmin, have expressed reservations over the tenor of Xi’s foreign policy.

Finally, although little in Xi’s domestic or foreign policy appears to welcome deeper engagement with the United States, Washington should resist framing its relationship with China as a competition. Treating China as a competitor or foe merely feeds Xi’s anti-Western narrative, undermines those in China pushing for moderation, and does little to advance bilateral cooperation and much to diminish the stature of the United States. Instead, the White House should pay particular attention to the evolution of Xi’s policies, taking advantage of those that could strengthen its relationship with China and pushing back against those that undermine U.S. interests. In the face of uncertainty over China’s future, U.S. policymakers must remain flexible and fleet-footed.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions