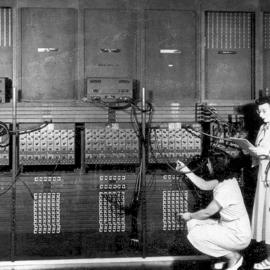

For much of the last century, the United States led the world in technological innovation—a position it owed in part to well-designed procurement programs at the Defense Department and NASA. During the 1940s, for example, the Pentagon funded the construction of the first general-purpose computer, designed initially to calculate artillery-firing tables for the U.S. Army. Two decades later, it developed the data communications network known as the ARPANET, a precursor to the Internet. Yet not since the 1980s have government contracts helped generate any major new technologies, despite large increases in funding for defense-related R & D. One major culprit was a shift to procurement efforts that benefit traditional defense contractors while shutting out start-ups.

Bad procurement policy is just one reason the United States has begun to lose its technological edge. Indeed, the multibillion-dollar valuations in Silicon Valley have obscured underlying problems in the way the United States develops and adopts technology. An increase in patent litigation, for example, has reduced venture capital financing and R & D investment for small firms, and strict employment regulations have strengthened large employers and prevented the spread of knowledge and skills across the industry. Although the United States remains innovative, government policies have, across the board, increasingly favored powerful interest groups at the expense of promising young start-ups, stifling technological innovation.

The root of the problem is the corrosive influence of money in politics. As more intense lobbying and ever-greater campaign contributions become the norm, special interests are more able to sway public officials. Indeed, these interests have overpowered start-ups across the government—at the Pentagon, in the courts, and in various state legislatures.

A STRICT SEPARATION

U.S. government procurement has spurred technological innovation since the early nineteenth century, when the U.S. War Department sought to develop the high-precision machines needed to make weapons from interchangeable parts. Over the next two centuries, government programs cultivated a corps of skilled engineers, technicians, and software developers fluent in cutting-edge technologies, who would later adapt them for general use in the private sector.

U.S. procurement programs worked so well in part because the Pentagon gave its business to a diverse group of private firms, including start-ups and university spinoffs such as Bolt, Beranek and Newman (now BBN Technologies), one of the companies that helped develop the Internet. It also required contractors to share their technologies with universities and other private firms, encouraging further innovation outside the government. By contrast, France and the United Kingdom often used government contracts to promote national telephone and computer companies, and the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union limited the interaction between government researchers and their civilian counterparts, cutting off the private sector from high-tech advancements. The Pentagon also encouraged contractors to adopt open technical standards—such as the set of protocols, established in 1982, that specified how data should be packaged and transmitted on the Internet—which allowed knowledge to spread quickly and easily.

In the past few decades, however, procurement has strayed from this successful formula. Instead of awarding contracts to start-ups and spinoffs, the Pentagon has favored traditional defense contractors. The Defense Department tasks these contractors with meeting the military’s narrow needs and too often prohibits them from sharing their work with universities or other companies. An example from the past reveals how problematic such policies can be. In 1977, when the Pentagon sought to create high-speed semiconductor chips, Congress prohibited the contractors hired from sharing their research. University researchers were effectively excluded from the program, and chipmakers were forced to separate their defense work from their commercial operations. Unlike the government procurement programs in the 1950s and 1960s, which spawned many start-ups, this billion-dollar program did little to commercialize new technology.

The more recent reliance on defense contractors reached an apex under Donald Rumsfeld’s second term as secretary of defense, from 2001 to 2006, when the Pentagon restricted bidding to major contractors, slashed funding to university researchers, restricted the participation of noncitizens in its programs, and classified most of the technology it produced. The Pentagon has relaxed some of its regulations since then—one recent cyberwarfare research program sought out computer hackers—but the larger trend persists.

The reason for the shift is simple: large defense contractors have the money and influence to secure lucrative government contracts. Although procurement has been the province of lobbyists since President Dwight Eisenhower’s 1961 warning about the “military-industrial complex,” the pure quantity of cash has skyrocketed. Since 1990, the defense industry has contributed more than $200 million to political campaigns, and in 2012 alone, it spent roughly $132 million on more than 900 lobbyists. Congress has its own interests, too. The defense R & D budget regularly includes pet projects for select congressional districts, most of which benefit large contractors, not universities and new firms.

OVERLY LITIGIOUS

Start-ups suffer not only from the Pentagon’s policies but also from the actions of the courts. The proliferation of patent litigation, in particular, has become a serious problem for small software firms, many of which make easy targets for aggressive lawyers. Such lawsuits are a relatively new phenomenon in the U.S. software industry, which grew up patent free. In 1972, the Supreme Court ruled that most software could not be patented, reasoning that unlike mechanical devices, abstract software algorithms are difficult to tie to a specific inventive concept. A decade later, however, after persistent lobbying by patent lawyers, Congress created the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, a new body designed to hear all appeals in patent cases. Such specialization is extremely rare, for good reason: it promotes boosterism. The new court, constantly seeking to expand its role, began sidestepping the Supreme Court in the 1990s, extending patent law to cover software. It also loosened its restrictions on vague-sounding patents, such as those for “information-manufacturing machines.”

The number of patents and lawsuits has surged as a result. A 2013 study by the Government Accountability Office found that the number of defendants in patent lawsuits more than doubled between 2007 and 2011; software patents accounted for 89 percent of the increase.

Many of these lawsuits are the work of “patent trolls”—companies that exist solely to buy and litigate patents. Patent trolls are particularly drawn to software patents, which are often vague enough to be widely applicable. In the early 1980s, for example, one inventor developed a kiosk for retail stores that could produce music tapes from digital downloads, filing a patent for an “information-manufacturing machine” at “a point of sale location.” A patent troll named E-Data later acquired the patent and interpreted it to cover all sorts of digital e-commerce, making millions of dollars from suits against more than 100 companies. Lodsys, another patent troll, bought an equally vague patent from 1992, which covered “methods and systems for gathering information from units of a commodity across a network.” It has now threatened to sue hundreds of smartphone application developers for infringement. As long as the courts remain receptive to their suits, patent trolls appear to be here to stay. And their suits are expensive. In 2011, the roughly 5,000 firms named as defendants in patent lawsuits paid more than $29 billion out of pocket.

In the early years of this century, software companies began pushing Congress to reform patent law, and in 2011, it passed the America Invents Act. More than 1,000 lobbyists worked on the bill, including ten former members of Congress, 280 former congressional staffers, and more than 50 former government officials. In the end, the software lobby was simply overpowered by patent lawyers and pharmaceutical companies, both of which benefit from the status quo in patent law—and are bigtime political donors. The new law did little to deter patent trolls or to discourage the vague software patents that allow trolls to abuse the system. In fact, the law granted relief to only one industry: finance. Thanks to pressure from politically powerful Wall Street executives, the law included a special provision allowing financial firms to challenge patents covering their services and products.

In December 2013, another bill designed to weaken patent trolls passed the House of Representatives, but pharmaceutical companies and trial lawyers once again blocked reform. This past May, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid prevented the bill from coming to the Senate floor for a vote. As long as reform stalls, software entrepreneurs will continue to suffer. President Barack Obama acknowledged as much in October, at a town hall meeting with technology entrepreneurs in California, where he cited concerns about “folks filing phony patents, and costing some of our best innovators tons of money in court, or even if they don’t go to court, having to pay them off just because they’re making a bogus claim.”

In much the same way, copyright law also punishes innovators. For much of the last century, copyright law was flexible enough to accommodate new technology—whether it was the player piano, the phonograph, the radio, the jukebox, the videotape player, or cable television. Sometimes the companies behind the new technologies had to pay licensing fees, but often they were initially exempt from copyright restrictions. Congress waited to intervene until new technologies were established enough to work out a fair compromise. Now, however, powerful content providers lobby Congress to ensure that new distribution channels are taxed or restricted while still in their infancy. In 1988, for example, lobbyists for network broadcasters and cable television companies convinced Congress to restrict the market for emerging satellite television providers, requiring them to pay hefty licensing fees to transmit to subscribers. A decade later, lobbyists for broadcast radio pushed for the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which forced Internet radio companies to pay larger royalties than those paid by traditional stations. Rather than accommodating new technologies, in other words, copyright law has been used to resist them.

CONSTRAINING COMPETITION

Yet another threat to start-ups comes from state legislatures, in the form of increasingly cumbersome employment regulations. Historically, technical workers such as mechanics and engineers moved freely from job to job, spreading new technologies across the industry. Today, however, a variety of regulations limit that mobility. Some states—Florida and Massachusetts, for instance—have made it easy for employers to enforce noncompete agreements, which prohibit employees from leaving one company to join or start another in the same industry. According to research conducted by the law firm Beck Reed Riden, the number of published U.S. court decisions involving noncompete agreements rose 61 percent from 2002 to 2012, to 760 cases. This is bad news for innovation, since such agreements make it difficult for start-ups to recruit employees away from established companies.

Consider the difference between California, whose courts generally do not enforce these agreements, and Massachusetts, whose do. Silicon Valley has become a breeding ground for new technology firms and new technologies, whereas Massachusetts’ Route 128 has fallen behind. It is telling that the Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg moved his company from Cambridge to Palo Alto as it took off. This past summer, state lawmakers in Massachusetts considered a ban on noncompete agreements, but powerful business lobbying groups fought hard against it, arguing that the agreements keep employees from stealing trade secrets and proprietary information.

Interest groups are also lobbying state legislatures to enforce strict requirements for certification to work in certain fields, another barrier to innovation. In the past few decades, occupational licensing has grown rapidly. In the 1950s, only 70 professions had licensing requirements; by 2008, more than 800 did. Political scientists have tied this surge to aggressive lobbying by professional associations. In 1995 alone, 850 licensure bills related to health professions were introduced in state legislatures, and more than 300 became law. But excessive licensing can be overly restrictive. In many states, for example, licensing regulations prevent nurse practitioners and dental hygienists from performing new preventive health procedures—such as applying protective varnishes and sealants to teeth—by restricting the carrying out of these procedures to doctors and dentists. Similar restrictions limit the adoption of new telemedicine and teledentistry technologies, which use videoconferencing and data transfer through smartphones and the Internet to connect doctors and dentists to patients in rural areas. In Alaska, for example, dental therapists travel to remote Native Alaskan villages to treat patients, often performing procedures with the help of dentists who consult remotely. In other states, however, occupational regulations limit the procedures dental therapists and hygienists can perform outside of a traditional dentist’s office, restricting the use of these technologies and reducing incentives to innovate further.

LOBBYING FOR THE FUTURE

Politics is about balancing competing interests. Opposing factions battle one another but ultimately compromise, each getting something it wants. In recent decades, however, start-ups have consistently lost out. Whereas established interests have the money and lobbying power to buy political influence, newer firms offer only the promise of future profits. As Jim Cooper, a Democratic congressman from Tennessee, has framed the problem, “The future has no lobbyists.”

Balance will be difficult to restore, given that money will likely remain a fixture of the U.S. political system. The cost of running for Congress has increased by more than 500 percent since 1984, and spending by registered Washington lobbyists has soared, more than doubling between 1998 and 2008. Efforts to curtail lobbying have largely failed, with the Supreme Court restricting legislation intended to rein in campaign spending. But if technology start-ups continue to suffer, the United States may lose what has been the very secret to its success.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions