Just two days after the terrorist attack at the offices of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo last January, Amedy Coulibaly, a French-born militant who had pledged allegiance to the self-proclaimed Islamic State (also known as ISIS), murdered four Jewish shoppers in a kosher supermarket in eastern Paris. Coulibaly’s heinous act was not without precedent. In 2014, Mehdi Nemmouche, a French citizen who had spent a year training with the Islamic State in Syria, opened fire in the Jewish Museum of Belgium, killing four. In 2012, Mohamed Merah, a French follower of al Qaeda, killed three children and a rabbi at a Jewish school in Toulouse.

Such attacks are the most visible signs of a wider trend: for the past 15 years, anti-Semitism has seemed to be on the rise in France. Long-standing economic and social problems fan the flames of interethnic tension in the modest communities where, since the 1960s, Jewish and Muslim immigrants used to live together in peace. French unemployment is high, surpassing ten percent overall, but among the youth in France’s poorer suburbs, where such tensions are most palpable, it is a staggering 40 percent, and schools are in crisis. Coulibaly, Nemmouche, and Merah all came from such communities. All three were born in France to parents who had emigrated from France’s former African colonies. They were raised as secular Muslims in neighborhoods where racism, poverty, and struggling schools limited their horizons. They became petty criminals in their teens and, as young men, found their way to Islamist terrorist movements, carrying out their anti-Semitic acts in the name of global jihad. As more and more people from such neighborhoods have followed this path, policing has increased, but the underlying economic and social problems persist.

The Sunday after the attacks on Charlie Hebdo and the kosher supermarket, 3.5 million people marched in the streets of France carrying signs expressing solidarity with the victims; most read, “I am Charlie,” but some also declared, “I am Jewish.” That evening, Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu (often called “Bibi”), visited Paris’ Grande Synagogue, making his entrance alongside France’s leaders: President François Hollande, Prime Minister Manuel Valls, former President Nicolas Sarkozy, and the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo. Although all these leaders have been remarkably supportive of France’s Jewish population in their public comments, with Valls going so far as to say that “France without Jews is not France,” it was Netanyahu whose entrance garnered the loudest applause, accompanied by chants of “Bibi! Bibi!” and “Israël vivra, Israël vaincra!” (“Israel will live, Israel will win!”). The enthusiastic reception reflected French Jews’ deep commitment to Zionism, which has only been strengthened in recent years.

The audience responded warmly to much of Netanyahu’s speech, at one point giving him a standing ovation. But when the Israeli leader addressed French Jews directly, telling them that Israel would welcome them with open arms, the reaction was rather different: members of the audience broke into an impassioned rendition of “La Marseillaise,” France’s national anthem. The message was clear: France’s Jews would stand with Netanyahu against the scourge of anti-Semitism but would not accept the suggestion—implicit in his invitation—that Jews did not fully belong in France. The unscripted, heartfelt response speaks to something deep within French Jewish culture that foreigners have some trouble seeing, much less understanding. For all their ardent Zionism, French Jews still have a deep faith in the values of the French Republic. Although Jewish emigration from France to Israel has increased sharply in recent years, 99 percent of France’s Jews are choosing to stay put rather than heed Netanyahu’s call. As the French Jewish writer Diana Pinto put it astutely:

The Europe we live in, despite its blatant faults, remains a place we are a part of not just politically as citizens, but also linguistically and culturally. . . . We have major stakes here, and not just petty personal reasons. Read the answers young European Jews . . . have written in response to the never-ending question of whether they might be leaving. Unlike in the ’30s, our governments protect us rather than excluding us and we are determined to improve our respective countries in terms of social justice and minority integration.

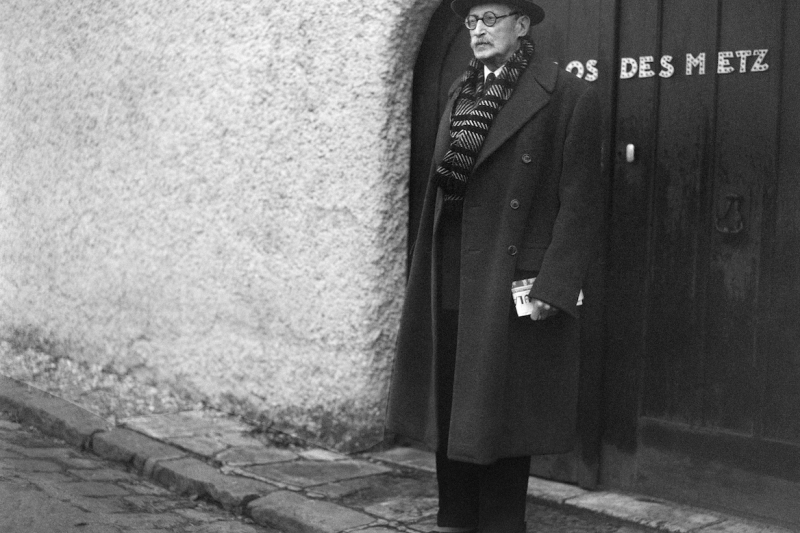

THE FIRST JEWISH PRIME MINISTER

One way to understand French Jews’ simultaneous attachment to Zionism and the French Republic is to turn to Pierre Birnbaum’s illuminating new biography of Léon Blum. In both his life story and his politics, Blum embodied the apparent contradictions at the heart of French Jewish identity. Born in 1872 to a bourgeois Jewish family in Alsace, Blum is today best remembered as the leader of the French socialist party (known by its French acronym, SFIO) and prime minister of France in 1936–37, during the Popular Front (and again, briefly, in 1938). Blum was a true devotee of what Birnbaum calls “republican socialism.” This is a socialism inflected with an abiding respect for the institutions of the democratic state, an admiration for the universalistic ideals of the French Enlightenment, and a commitment to redressing the ills caused by economic inequality.

For all their ardent Zionism, French Jews still have a deep faith in the values of the French Republic.

But even as Blum’s politics were decidedly universalistic, recognizing no distinction between “Jewish” problems and general problems, Blum came to his convictions as a Jew and proudly brandished his Jewish identity in public, even when it made him a target for some of the most vicious anti-Semites France has ever seen. He was a committed Zionist and served as president of the French Zionist Union. Blum saw no contradiction in this. As he said in a 1929 speech, “I am Zionist because I am French, Jewish, and Socialist, because modern Jewish Palestine represents a unique and unprecedented encounter between humanity’s oldest traditions and its boldest and most recent search for liberty and social justice.” As have many French Jews today, in the 1930s, Blum responded to the rising tide of anti-Semitism by doubling down on both his Zionism and his belief in the values associated with the French Revolution, because he saw a fundamental connection between Jewish security and the universal promise of republican democracy.

As Birnbaum deftly reveals, the young Blum came to politics as a second career (he first was a writer and literary critic) in response to the Dreyfus Affair, a national scandal that broke out in the late 1890s after Alfred Dreyfus, a French Jewish army captain, was accused, tried, and wrongly convicted of treason. Blum was fiercely critical of other French Jews whose response, he claimed, “was to bury their heads in the sand” rather than stand and fight on Dreyfus’ behalf. But Blum ignored the larger picture: he was, in fact, far from alone in his outrage. As Birnbaum shows, drawing from his fascinating and original study of the Dreyfus Affair, The Anti-Semitic Moment, published in 2003, many French Jews—from military officers to religious leaders to low-level civil servants—became “Dreyfusards,” advocating for Dreyfus and even fighting armed duels with anti-Semites. Most important, the affair led many French Jews to get involved in politics—for example, by helping found the Human Rights League, which opposes all forms of discrimination.

For Blum, it was Jean Jaurès, one of the first leaders of the SFIO, who offered the most meaningful response to the Dreyfus Affair, by seeking to defend the individual by promoting social justice for all. Not Jewish himself, Jaurès was a moderate Socialist who was committed to the rule of law and the democratic process, with a modest and honest demeanor that garnered him broad support within and beyond the SFIO. Jaurès’ choice to join the Dreyfusards represented an important turning point in his party’s history. Rather than simply focus on the class struggle—which made other Socialists indifferent to the fate of the bourgeois Dreyfus and largely hostile to Jews as a group, since Jews were not generally members of the French working class—Jaurès saw the affair as a case of violated rights. For him, the French state should have been expected to guarantee individual rights, and thus in this case, it should be pushed to exculpate the wrongly accused captain. Unlike socialist parties in other countries, the SFIO that Blum joined saw the republican state as, in Jaurès’ words, the “political form of socialism” and sought to complete the French Revolution’s promise of social equality through the ballot box.

After Jaurès was assassinated in 1914, Blum carried on in his political footsteps, and when the SFIO split in December 1920—with the majority breaking off to form the Moscow-aligned French Communist Party—Blum took over the leadership of the party’s remnants and stayed faithful to the republic. When Blum became prime minister with the victory of the Popular Front coalition in 1936, he proved his willingness to compromise rather than conquer, out of respect for the democratic process. As his detractors never fail to point out, this hampered his ability to achieve much in the areas in which the left-wing parties disagreed. His refusal to intervene in the Spanish Civil War, the failure to resolve the future of France’s colonial empire, and France’s inadequate responses to the Nazi threat and the Jewish refugee crisis have all been criticized by historians in the decades since. Even so, his tenure saw the passage of historic legislation: a French “New Deal” that greatly expanded workers’ rights by securing unemployment insurance, greater collective-bargaining rights, paid vacations, and the 40-hour workweek.

“WILL FRANCE BE ISRAEL’S SOLDIER?”

The fact that a Jew such as Blum could rise to such political heights in the 1930s is astonishing and could have happened only in France, where Jews have arguably been more successful in politics than anywhere else outside Israel. Even in the United States, where Jews have long represented a larger proportion of the population than they do in France, no Jew has reached Blum’s level. Indeed, as far back as the 1840s, French Jews have served in important state positions, as deputies, prefects, ministers, judges, and army officers, in numbers entirely disproportionate to their population.

Birnbaum insightfully situates Blum within this tradition of “state Jews,” who benefited from French republicanism’s revolutionary mission to shake up traditional Catholic society with secularizing, modernizing programs. Particularly during the Third Republic (1870–1940), a great number of Jews devoted their lives to state service and believed fully in the equalizing promise of France’s meritocratic, secular institutions and programs. Although in certain ways, they were assimilated—they lived their lives in French and dedicated themselves to secular pursuits—they nonetheless did not convert to Christianity or marry gentiles in significant numbers (unlike, say, German Jews), and many took on leadership positions within Jewish associations. Ideologically, this double commitment was easily maintained, for since the time of Napoleon, French Jews had connected their Judaism with the values of the French Revolution. Blum’s belief in the emancipating potential of the republic thus grew as much out of his Jewish background as it did out of his adherence to Jauresian socialism.

And yet Jews such as Blum did face difficulties in public life. In 1936, just before he took office as prime minister, Blum was attacked by a mob of young right-wing militants, who dragged him from his car and beat him nearly to death. After the attack, Blum wrote, “I know now what lynching means.” Birnbaum’s portrait begins by quoting some of the racist vitriol Blum encountered while serving as prime minster, even within the Chamber of Deputies, where several cries of “Death to the Jews!” were heard.

Tying their identities and their security to the unstable Third Republic made state Jews vulnerable. By a disturbing logic, the association of Jews with the republic, and particularly with its socially transformative agenda, came to be seen by anti-Semites as the co-optation of the republic by the Jews. The anti-Semitic rhetoric targeting Blum reached a fever pitch in October 1938, when the normally pacifistic politician sought to persuade his fellow deputies of the importance of confronting Hitler with military force. In response, the right-wing press sought to discredit Blum’s position by tying it to his Jewishness and by invoking anti-Semitic conspiracy theories. “Warmonger Blum is the real master of ceremonies,” cried the nationalist newspaper La Revue Hebdomadaire. “Will France be Israel’s soldier and Yahweh’s instrument against the gentiles?”

Now, as then, economic and political crises fuel anti-Semitism.

Given such rhetoric on the eve of World War II, it is no surprise that Blum was imprisoned in 1940 by the French Vichy authorities who collaborated with the Nazis and was charged with having “betrayed the duties of his office.” Blum defended himself at his trial by arguing that the Vichy regime was not “trying a man or a head of government but the republican regime and the republican principle itself.” The foreign press so applauded Blum’s defense that the regime feared its legitimacy was being called into question, and so prosecutors called an end to the trial before a verdict could be delivered. Blum was eventually handed over to the Germans, who held him for two years in the concentration camp at Buchenwald under special guard, hoping to use him in a potential future prisoner exchange. He was liberated in 1945 by a group of Italian partisans and American soldiers and returned to France, where he reentered political life briefly before retiring in late 1947.

PLUS ÇA CHANGE?

Today’s anti-Semitism is not the kind Blum faced. Yet the shadow of the 1930s still looms over Europe’s Jews and has led anxious commentators to compare the two types, sometimes in order to call for a mass exodus of French Jews. Many of these comparisons are tendentious, ignoring key differences between the two periods. Most important, the role of the state is quite different now. In France, thousands of armed troops were deployed after the attack on the supermarket to stand guard in front of synagogues and Jewish schools; anti-Semitic speech is monitored, sometimes even prosecuted; and state leaders—Valls especially—have made public statements insisting that the right place for French Jews is in France. Moreover, the new anti-Semitism is a global phenomenon; it is pure fantasy (if a politically expedient one) to imagine that European Jews would be safer from anti-Semitic terrorism in Israel than they are in Europe. And who knows what Blum would have made of the far-right National Front’s recent attempts to increase its support among Jews, as it seeks to build a broader coalition against Muslim immigration.

But Birnbaum’s insightful account allows readers to consider the comparison between today’s anti-Semitism and that of an earlier era and opens up new ways of thinking about the present. For all the differences, there are some basic structural similarities. Now, as then, economic and political crises fuel anti-Semitism. Democracies around the world face challenges from identity-based, purity-seeking movements, which have proved quite dangerous. Racism still limits opportunities for many, and economic inequality within countries is increasing dramatically. These problems, and not a supposed “clash of civilizations” between Islam and Judeo-Christian traditions, are what drive contemporary anti-Semitism, and they must be seen as general, not just Jewish, problems—just as Blum would have seen them. Even as French Jews become increasingly aware of their particular vulnerability to hate crimes, most will make the choice that Blum made: they will put their faith in the republic’s democratic institutions and values.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions