Despite boasting the most powerful economy on earth, the United States too often reaches for the gun instead of the purse in its foreign policy. The country has hardly outgrown its need for military force, but over the past several decades, it has increasingly forgotten a tradition that stretches back to the nation’s founding: the use of economic instruments to accomplish geopolitical objectives, a practice we term “geoeconomics.”

It wasn’t always this way. For the country’s first 200 years, U.S. policymakers regularly employed economic means to achieve strategic interests. But somewhere along the way, the United States began to tell itself a different story about geoeconomics. Around the time of the Vietnam War, and on through the later stages of the Cold War, policymakers began to see economics as a realm with an authority and logic all its own, no longer subjugated to state power—and best kept protected from unseemly geopolitical incursions. International economic policymaking emerged as the near-exclusive province of economists and like-minded policymakers. No longer was it readily available to foreign policy practitioners as a means of working the United States’ geopolitical will in the world.

The main reason the United States abandoned geoeconomics may have less to do with evolving foreign policy habits than with evolving economic beliefs.

The consequences have been profound. At the very time that economic statecraft has become a lost art in the United States, U.S. adversaries are embracing it. China, Russia, and other countries now routinely look to geoeconomics as a means of first resort, often to undermine U.S. power and influence. The United States’ reluctance to play that game weakens the confidence of U.S. allies in Asia and Europe. It encourages China to coerce neighbors and lessens their ability to resist and gives Beijing free rein in vulnerable states in Africa and Latin America. It allows Russia to bend much of the former Soviet space to its will. It reduces U.S. influence in friendly Arab capitals. It allows poverty to flourish in the Middle East, nourishing Islamic radicalism. These costs weigh on specific U.S. aims, but they also risk accumulating over time into a structural disadvantage that Washington may find hard to reverse. It is long past time for the United States to restore geoeconomics to its rightful role.

SURVIVAL FIRST

In the years following the American Revolution, the Founding Fathers understood that the United States could never achieve true independence unless it became economically self-sufficient. But more than that, these early leaders, facing predatory European nations and possessing little ability to project power abroad, instinctively reached for economics as their preferred—at times their only—means to protect their young and vulnerable country. Keenly aware that European states were the most likely source of threats, Benjamin Franklin suggested that the United States offer its commerce in exchange for their goodwill. In Common Sense, Thomas Paine explained how the United States could insulate itself from Europe’s eighteenth-century power struggles by turning to geoeconomics: “Our plan is commerce, and that, well attended to, will secure us the peace and friendship of all Europe; because it is the interest of all Europe to have America a free port. Her trade will always be a protection.”

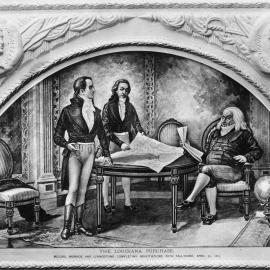

In a rare point of agreement between them, Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson shared a basic enthusiasm for economic tools of foreign policy. Hamilton, the father of American capitalism, stressed the value of commerce as a weapon, a proposition that few trade policymakers would agree with today. Jefferson scored one of the country’s greatest geoeconomic successes in its history when he oversaw the 1803 purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France, which doubled the size of the United States for four cents an acre. As much as Jefferson liked a good deal, his fundamental motivation was geopolitical. In 1801, while the territory was still under Spanish control, he confided his fears about its future to James Monroe, writing, “We have great reason to fear that Spain is to cede Louisiana and the Floridas to France.” Jefferson knew that if France acquired and held on to these territories, it would be emboldened to expand its holdings, setting the United States up for a military confrontation that it almost certainly could not win.

During the Civil War, the North persuaded the United Kingdom to stop supporting the South in part through economic intimidation: it threatened to confiscate British investments in U.S. securities and to cease all trade, including grain shipments. Later, as the task turned from war fighting to reconstruction, U.S. leaders pursued geoeconomic openings that would not merely restore their newly unified country but also strengthen it beyond its prewar position. Secretary of State William Seward negotiated the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867, increasing the country’s size by nearly 600,000 square miles. Despite a bargain price of two cents an acre, the deal was derided in Congress and the press. History would vindicate the purchase Seward secured, since it helped propel the United States from a continental power to an international empire. Indeed, had it not been for “Seward’s Folly,” his successors would have had a far more claustrophobic Cold War on their hands.

TOTAL WAR

World War I profoundly shifted the United States’ relationship with geoeconomics. At the beginning, the United States clung to its policy of neutrality in trade. But once Washington entered the war, in 1917, it enacted draconian economic embargoes. Within months, the United States pivoted to full cooperation with the Allies’ food blockade of Germany and then embargoed all exports to the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands, all of which had stayed neutral.

The United States’ early geoeconomic pursuits were not without controversy, but disagreements turned mainly on how, not whether, to use economic influence. President Woodrow Wilson entered office deeply opposed to “dollar diplomacy,” his predecessors’ policy of encouraging overseas investment to further U.S. interests. Yet Wilson took issue with the ends, not the means. He said he remained “willing to get anything for an American that money and enterprise can obtain, except the suppression of the rights of other men.” Sure enough, by 1919, as the country’s main object in Europe shifted from winning the war to securing the peace, Wilson advanced a largely geoeconomic solution. He persuaded the new League of Nations that its best hope of preventing another war was an “absolute” boycott on aggressor countries. “Apply this economic, peaceful, silent, deadly remedy and there will be no need for force,” Wilson urged.

Even as isolationist sentiment swelled in the United States after World War I, the country was still honing its geoeconomic reflexes around the world. As the United States grew tired of Europe’s military dilemmas, it turned to facilitating private investment overseas in an effort to expand U.S. influence. In 1924, for instance, it spearheaded the Dawes Plan, which allowed U.S. banks to lend Germany enough money to pay war reparations to France and the United Kingdom.

After President Franklin Roosevelt took office in 1933, his administration embraced geoeconomics to preempt German encroachment in the Western Hemisphere. Between 1934 and 1945, the United States signed 29 reciprocal trade agreements with various Latin American countries. And in Asia, the administration tried to use the Export-Import Bank to blunt the rise of Japan. Citing a “bare chance we may still keep a democratic form of government in the Pacific,” Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr., arranged a $25 million loan to China in 1938.

Then World War II broke out, and Washington’s geoeconomic policies went into overdrive. In 1941, Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act, under which the United States supplied Allied nations with some $50 billion worth of military supplies (equivalent to about $660 billion worth today). If the lend-lease policy was, in the words of Secretary of War Henry Stimson, “a declaration of economic war,” many British felt that it was directed as much at London as Berlin. Their complaints were not entirely unfounded: under lend-lease, Washington meddled in British economic affairs to a degree that is almost unimaginable today, managing British exports, seeking unilateral control over levels of British gold and dollar reserves, and extracting British concessions concerning the terms of the postwar order.

In 1943, the U.S. government even established the Office of Economic Warfare, an agency charged with safeguarding the U.S. dollar. Its more than 200 market analysts around the world and nearly 3,000 experts in Washington did so by helping U.S. producers increase exports and securing vital imports at favorable terms. A year later, delegates from the Allied countries signed the Bretton Woods agreement. The goal was not trade for trade’s sake but, as Secretary of State Cordell Hull explained, “a freer flow of trade . . . so that the living standards of all countries might rise, thereby eliminating the economic dissatisfaction that breeds war” and imparting “a reasonable chance of lasting peace.” That goal, of course, would go on to usher in a lasting peace on the United States’ terms.

THE GOLDEN AGE OF GEOECONOMICS

The United States’ geoeconomic instinct survived World War II, abetted by U.S. economic dominance and the Soviet Union’s economic isolation. As a consensus emerged that it was economic crisis that had led to the rise of aggressive dictatorships and the subsequent war, U.S. policymakers reached for economic tools to promote peace. Perhaps the best-known example is the Marshall Plan, for rebuilding postwar Europe. Although Secretary of State George Marshall never mentioned communism or the Soviet Union in his 1947 speech outlining the policy, its architects were candid about its geopolitical objectives. As the diplomat George Kennan explained, the plan would combat “the economic maladjustment which makes European society vulnerable to . . . totalitarian movements and which Russian communism is now exploiting.” President Harry Truman himself admitted that “the military assistance program and the European recovery program are part and parcel of the same policy.” Had Truman failed to persuade Congress to spend the $13 billion it ultimately did on the economic recovery half of his equation, the Cold War could well have cost the United States far more in blood and treasure than it did.

The first successful Soviet nuclear test, in 1949, and the outbreak of the Korean War, in 1950, marked the opening scenes of the Cold War and pulled Washington toward a more assertive strategy of containment. But the turn did not mark any shift away from geoeconomics, at least not initially. To the contrary, the United States overcame stiff European reluctance to expand the West’s embargo on China. In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower came into office committed to the idea of achieving both absolute and relative economic gains through East-West trade, which required easing the embargo that the United States had levied on the Soviet Union. Like Wilson, however, Eisenhower did not object to the use of embargoes for geopolitical ends; rather, he doubted that this particular one would best serve those ends.

Once Washington entered World War I, it pivoted to full cooperation with the Allies’ food blockade of Germany.

Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson thought likewise. For Kennedy, further easing the U.S. embargoes against communist countries made sense not because they were having no real economic impact (as many at the time thought) but because doing so might elicit quid pro quos from the Soviets. In that vein, Johnson seized on a split between the Soviet Union and Romania, normalizing trade relations with Romania in 1964 and supplying it with a package of commercial incentives the following year.

Even as Washington trained much of its attention on Europe during the early Cold War, it never lost sight of Asia. After the Korean War, the United States guarded against the risk of collapse or a communist takeover in South Korea by showering the country with grants and loans. Absent this aid, the United States would almost certainly face a much tougher geopolitical landscape on the Korean Peninsula today; at a minimum, Seoul would not be the highly capable ally it is. The dynamic with Japan was different, since Tokyo resisted pressure to open its economy and clung to mercantilist trade and monetary policies that Washington saw as distinctly unhelpful to U.S. interests. But even in this relationship, geopolitical concerns trumped narrow economic interests, with the United States unwilling to risk an outright trade war with Japan for fear of pushing it toward the Soviet Union.

FALLING OUT OF FASHION

Over the course of the Cold War, the United States increasingly construed its policy of containment in military terms. The Vietnam War was partly to blame; it was perhaps inevitable that armed conflict involving U.S. troops in Southeast Asia would cause policymakers to look more toward military force. But that is only part of the story. During the 1960s, commercial interests gained greater influence in Washington and complained that the State Department failed to appreciate U.S. economic concerns. In 1962, congressional leaders even refused to launch a new round of trade negotiations unless Kennedy set up a White House office to promote trade.

It was not until Richard Nixon’s presidency, however, that geoeconomics began to fall off the radar. Although Nixon dangled economic incentives when pursuing the opening to China, he and his advisers viewed these as secondary in importance. Likewise, they saw détente with the Soviets as a largely geopolitical exercise with very little economic content. At that time, the dollar-based system of fixed exchange rates established at Bretton Woods was eroding, thus undermining the anti-Soviet coalition; as the writer Walter Russell Mead has argued, a more economically inclined administration would have viewed the threat as “far greater than anything Ho Chi Minh could ever assemble in the far-off jungles of Indochina.” For Nixon, however, monetary coordination was hardly the stuff of first-order foreign policy. “I don’t give a shit about the lira!” he once told his chief of staff. He underscored the point in 1971, when he abandoned the dollar’s convertibility into gold, ending the accommodating monetary policy that the United States had extended to its allies since 1945.

Nixon was not alone in his disdain for geoeconomics. Slowly but surely, the U.S. government grew less enamored of the practice. Congress intensified its skepticism of trade as a foreign policy tool, convening several committees to scrutinize U.S. trade restrictions against the Soviet bloc and, in 1969, passing a bill liberalizing East-West trade that went beyond what Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, wanted. In 1972, U.S. farmers successfully opposed the hotly debated proposal to hold grain sales to the Soviets hostage to political concessions. When the issue came up again a few years later, Kissinger was not happy about opposition to the policy. For him, exchanging grain merely for money was “very painful,” since the asset could have been used instead to extract substantive changes in Soviet behavior. From that moment on, Washington’s foreign policy mandarins were put on notice: purely economic interests would prevail over geopolitical ones.

President Jimmy Carter made intermittent shows of geoeconomic strategy. In the early days of the Iran hostage crisis, in 1979, the U.S. government froze Iranian assets because, as Carter later wrote about Iran’s leaders, “I thought that depriving them of about twelve billion dollars in ready assets was a good way to get their attention.” The next year, Carter initiated a grain embargo against the Soviet Union as punishment for its invasion of Afghanistan. But the public viewed the policy as a failure—feeding the view of economic statecraft as ineffectual—and President Ronald Reagan repealed it. When the United States negotiated a new grain agreement with the Soviets in 1983, it explicitly forbade the United States from banning exports for reasons of foreign policy.

After the Soviet Union collapsed, U.S. diplomats occupied themselves with transitioning the former Soviet countries toward democratic capitalism, and the economic components of the plan focused squarely on economic outcomes. Washington pushed for trade and investment reforms for the sake of deeper, faster, more efficient, and better-integrated markets. Economists would coin the term “the Washington consensus” as a shorthand for the mix of economic measures all market economies in good standing would have to accept; critics would dub it “the Golden Straitjacket” for the way it constrained policymakers from deviating from the prescription even for domestic economic reasons, let alone geopolitical ones.

Even though President Bill Clinton’s first formal articulation of U.S. national security strategy identified a central goal as “to bolster America’s economic revitalization,” economic instruments figured little in U.S. foreign policy during his tenure. The notable exception was sanctions, which grew in scope and sophistication under Clinton. But for the most part, the administration reached first for political and military tools as it sought to assert U.S. leadership throughout the world. It was also during this period that U.S. and European governments did very little economically to shape the direction of Russia under Boris Yeltsin—a profound omission that, since it enabled the rise of Vladimir Putin’s neoimperialism, haunts the world today.

Then came 9/11, which arguably made the shift to an even more militarized national security strategy inevitable. Although the George W. Bush administration tried to curtail terrorist financing, al Qaeda and its affiliates were hardly vulnerable to economic coercion; the war on terrorism would have to be fought by ground forces, combat aircraft, and armed drones.

WHAT CHANGED?

Given how adept at economic statecraft the United States once was, why have policymakers largely forgotten the practice? Part of the answer lies in the Cold War’s military dimension, which must have weighed heavily on the minds of decision-makers who faced crisis after crisis. Material factors were important, too: the onset of economic insecurity in the United States in the 1970s and the rise of the multinational corporation (and, with it, an organized political lobby for trade). Institutional factors played a role, as well. From the 1980s onward, bureaucratic momentum shifted from the State Department to the Pentagon, and the trade office that Kennedy had established in the White House ballooned into the much larger and more powerful Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

But the main reason the United States abandoned geoeconomics may have less to do with evolving foreign policy habits than with evolving economic beliefs—in particular, economists’ growing reluctance to see themselves and their discipline as embedded in larger realities of state power. The standard-bearers of economic thought during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had little problem using economics as an instrument of state power, whereas their neoclassical successors thought that markets were best kept free from geopolitical interference. Their worldview happened to fit the Cold War well: with the Soviet Union opposed to free trade, a gain for free trade anywhere was a gain for the West.

The neoclassical economic orthodoxy survived the Cold War, as did the resulting divide between economists and foreign policy thinkers. For two decades, none of this mattered, since the United States faced no serious strategic challenge and thus had no reason to revisit whether neoclassical ideas still aligned with the country’s foreign policy goals. Today, however, tensions between neoclassical economics and U.S. foreign policy have arisen. Many states now appear entirely comfortable employing economic tools to advance their power, often at the expense of Washington’s. China, for instance, curtails the import of Japanese cars to signal its disapproval of Japan’s security policies. It lets Philippine bananas rot on China’s wharfs to protest Manila’s stance on territorial disputes in the South China Sea. It rewards Taiwanese companies that march to Beijing’s cadence, and punishes those that do not. Russia, meanwhile, bans imports of Moldovan wine as Moldova weighs deeper cooperation with the EU, and Moscow periodically reduces energy supplies to its neighbors during political disagreements. It dangles the prospect of an economic bailout to Cyprus in return for access to its ports and airfields, forcing EU leaders to choose between coming through with a sufficiently attractive bailout of their own and living with a Russian military presence inside the EU.

In the 1960s, commercial interests complained that the State Department failed to appreciate U.S. economic concerns.

Such moves can sit uncomfortably with the tenets of neoclassical economics, which has difficulty accounting for the geopolitical aims of adversaries’ economic policies. For U.S. policymakers, recognizing the geopolitical motivations behind such economic power plays need not necessarily mean responding in kind. Still, they should recall the advice of John Maynard Keynes and other economists who saw themselves as guided by the prevailing realities of state power—and who saw a danger in illusions to the contrary.

A NEW BRAND OF STATECRAFT

The time has come for the U.S. foreign policy establishment to rethink some of its most basic premises about power and economics. Although reasonable minds can differ on the specifics of a geoeconomic vision, it is worth ensuring that it derives from the right framework. Four features are essential.

First, strategists need to think about new tools. A clearer reading of U.S. history no doubt offers insights into geoeconomics’ rightful role today, but the world has changed too much for policymakers to revert to earlier playbooks. Many of Jefferson’s and Marshall’s geoeconomic feats would be unthinkable today, and some of today’s favored geoeconomic tools, such as state-sponsored cyber-warriors who hack foreign companies’ networks, have become available only recently. Others, such as sanctions or energy politics, although nothing new, now operate in such vastly different landscapes as to render them good as new. Any effort to put geoeconomics back in foreign policy needs to begin with ascertaining what its modern instruments are, how they work, and what factors make them more or less effective. That will have to entail a set of debates—stretching across U.S. universities and think tanks, Congress, and the executive branch—that begin to set geoeconomics apart as a distinct discipline, endowed with its own principles that can guide action in specific cases.

Second, the United States needs to figure out its own norms for the acceptable use of geoeconomics. With the largest economy in the world, a shale boom that is remaking geopolitical realities around the world, and a financial sector through which the vast majority of global transactions must pass, the country still has a lot to work with. But before choosing to use its economic heft, Washington has to decide just how comfortable it is doing so.

The task is not easy, since many geoeconomic approaches carry real tradeoffs. But this is true of every foreign policy option. Too often, geoeconomic approaches are considered in isolation, unlike those involving military statecraft, which tend to be debated within the logic of best-known alternatives. The criticism that a given sanctions program is misguided because its costs outweigh its benefits, for example, misses the real question of how these tradeoffs compare to those of other political or military options. Policymakers also tend to measure geoeconomic plans by the wrong standards—judging them by their economic, rather than their geopolitical, impacts.

But even when assessed more logically, certain geoeconomic tools may simply be out of the question for the United States. This is partly a result of the country’s beginnings as an experiment in the deliberate curtailing of state power; democratic constraints prevent a U.S. president from, for example, suspending private contracts with foreign governments to gain leverage in a geopolitical dispute. Moreover, as the world’s leading supplier of public goods—underwriting the world’s deepest capital markets, issuing the world’s leading reserve currency, securing maritime trade routes—the United States has a genuine geopolitical interest in keeping shows of economic coercion to a minimum. For now, however, it is hardly clear that Washington’s discomfort with geoeconomics reflects anything more than the residual workings of a set of assumptions honed in the past several decades. There are no doubt legitimate debates to be had about the wisdom of various geoeconomic approaches. But these are debates worth having.

Third, the United States needs to work geoeconomics into the bloodstream of its foreign policy. At a minimum, that will require U.S. leaders to explain in detail to the American public and U.S. allies what today’s brand of geoeconomics consists of. When U.S. diplomats meet with their foreign counterparts, they should devote time to forging a common understanding about the rightful role of geoeconomic power in grand strategy. Leaders will also need to call out geoeconomic coercion when it takes place, so as to put countries on notice that it will not go unanswered, and develop responses to it with like-minded partners.

Fourth, policymakers need to grapple with important questions about how to allocate resources within the realm of foreign policy, whatever one thinks of overall spending levels. They need to ask, for example, what the United States is getting for its post-9/11 military spending. The answer is, less and less: although military power is of course still vital, it is yielding diminishing returns. So Congress should shift the Pentagon’s resources toward the application of economic instruments to advance U.S. national interests—say, foreign aid or investment promotion.

In making these policy shifts, the United States would regain its status as a powerful geoeconomic actor on the world stage. It would acquire the ability to counter the growing economic coercion practiced by authoritarian governments in Asia and Europe against their neighbors and beyond. The leading democracies would gain new tools for shaping geopolitics in positive ways. And the United States’ system of alliances would grow stronger, thereby reinforcing regional orders and the global balance of power.

Of course, none of these measures can be implemented in a day, and many will take years to be put in practice. Indeed, adopting them will require a fundamental shift in how the United States defines foreign policy—an intellectual shift that can come about only with presidential leadership and sustained congressional support. And so whether the next administration and Congress digests this compelling reality will rank among the most important questions of American grand strategy.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions