On September 2, 1985, the SS Bashan cruised through the green-leaved gorges of the Yangtze River, its prow breaking the waters along its 259-foot length. Inside, the river’s shifting light played off the hallways, staterooms, and modish decorations, and air conditioning kept the late-summer heat at bay. The luxurious cruise ship had entered service earlier that year, with room for nearly 150 passengers curious to see sights advertised as “inspir[ing] romantic poets and painters with [a] sense of timelessness, awesome beauty, and endless energy.” But the spacious decks of the Bashan were strangely empty.

Nearly everyone onboard was massed in the main hall, where a world of accents resounded: American, Chinese, German, Hungarian, Polish, Scottish. All eyes were fixed on a man with elfin features behind thick-rimmed glasses, wearing a long-sleeved white shirt and no jacket: the Hungarian economist Janos Kornai. Behind him was an incongruous prop for a river cruise, a blackboard on which he had sketched out economic models. On his left, Ma Hong, one of China’s leading policymakers, listened attentively, and a few seats away, Xue Muqiao, China’s most famous economist, sat smoking. The American economist and Nobel laureate James Tobin and the Scottish economist Sir Alec Cairncross were also in attendance. Elsewhere in the room sat two young Chinese scholars: Lou Jiwei, now China’s finance minister, and Guo Shuqing, who currently governs Shandong, one of China’s richest provinces.

The cruise ship was hosting a weeklong meeting of some of the world’s most brilliant economists, who had assembled to figure out a plan for China’s troubled economy. The gathering came at the zenith of an era when officials under Deng Xiaoping were scouring the globe for fresh ideas that would set China on the path to prosperity and global economic power.

The orders to gather the group onboard the Bashan had come directly from the top official in charge of the economic reforms already under way, Premier Zhao Ziyang. Zhao believed that China should “make up for [its] weak points through international exchange” and use foreign ideas to reform its failed socialist economy. So China’s rulers sought advice from abroad. Western experts offered ideas about how to introduce more market-based elements into the Chinese system and modernize the government’s role in the economy. The secluded Bashan was the setting of the single most important of these many exchanges. The ideas discussed there would propel a shift in China to the mixed “socialist market economy” that exists today and has powered China’s economic boom.

“It seems to be a most unusually interesting opportunity,” wrote Tobin in a letter to his Yale department chair, asking permission to miss the first week of classes to attend the conference. “The idea seems to be to detach the high officials from their desks and phones so they can concentrate on learning some of the unpleasant facts about managing decentralized economies.”

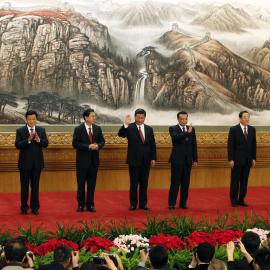

Although it began only 40 years ago, China’s age of openness now seems to be slipping away. Chinese President Xi Jinping is presiding over a turn toward intellectual isolation and distrust of the outside world. Leading Chinese officials and publications regularly decry what the party calls “hostile foreign forces.” Beijing has introduced new rules designed to eliminate “Western values” from the educational system, promote Internet sovereignty, and control the media. And in April 2016, the Communist Party cracked down on foreign nongovernmental organizations, passing a law that created demanding new registration requirements, increased government monitoring, and limited their contact with Chinese entities; The New York Times called it “the latest in a series of actions taken by Mr. Xi against the kind of Western influences and ideas that he and other leaders view as a threat to the survival of the Communist Party.”

What Deng knew, and Xi seems to ignore, is that China succeeds not by limiting its connections to the outside world but by opening itself up to new ideas wherever they may originate. Today, China’s economy is teetering. Growth is slowing, investor confidence is falling, and debt is rising. According to The Economist, the government spent approximately $200 billion to support the stock market between May 2015 and May 2016; around 40 percent of China’s new debt goes to pay interest on its existing loans. If Xi thinks he can make the breakthroughs necessary to save the Chinese economy without drawing on the best ideas from around the world, he faces long odds. It is far smarter to bet China’s future on openness than on isolation.

“THE OLD IDEAS WON'T DO”

China in the 1980s was still a country of drab gray buildings—a place where bicycles, not cars, clogged the roads. When Mao Zedong died in 1976 and the Cultural Revolution ended, China’s centrally planned economy was in a shambles. Mao had despised capitalism: in 1950, he had trumpeted, “The Soviet Union’s today will be our tomorrow.” But millions had died from famines and violent campaigns under Mao’s leadership, and his death allowed for a sweeping reassessment of China’s path.

Beginning almost the moment that Mao died, the government invited foreign economists—from Czechoslovakia, Poland, the United Kingdom, the United States, and beyond—to China to provide advice, and China’s new leaders under Deng traveled abroad to study other systems. Visiting Japan, the United States, and Western Europe, they were stunned at how backward China’s economy had become. When Deng visited the United States in 1979, China’s per capita GDP was still well under $200—less than one-50th of that of the United States.

So Deng and his colleagues set out to make China rich. The transformation of the economy began in the countryside. The key reforms provided incentives for farmers to produce more than the state-set amount and sell the surplus at whatever price they could get. The reforms soon moved into the cities, but by 1985, the new urban and industrial policies had run into immense difficulties. State-owned enterprises, which produced the majority of China’s industrial output, resisted market-oriented change. Growth was soaring uncontrollably, wildly surpassing expectations, but inflation was rising with it. Conservatives within the party made clear that they were ready to put the reforms on hold, and perhaps even toss Zhao out. China’s rulers wanted the country to get rich, but not at the cost of control. It was Zhao’s job to square the circle.

With the stakes this high, Zhao needed as many options as he could get. “The old ideas won’t do,” he was fond of saying. The delegation of international economists who came to China in the summer of 1985 for the cruise offered the possibility of new ideas that could help save China’s reforms.

On August 31, 1985, Zhao, with his oversized black-rimmed glasses and graying, swept-back hair, met with the visitors at Zhongnanhai, the imperial compound in Beijing that serves as the central headquarters of the government and the Communist Party. The premier asked the group’s advice on how to improve China’s economy and handle urban economic reform. He singled out the problems of overheated growth: factories were churning out products without clear demand, inflation was rising, and consumers, who were used to stability, were growing anxious.

“All this came out with [a] directness, simplicity, and frankness that seemed quite natural until one stopped to think that the speaker was the Prime Minister of the largest country on earth, canvassing advice from an assorted group of foreign economists,” Cairncross, the founding director of the World Bank’s Economic Development Institute (now called the World Bank Institute), wrote in his diary. “Where else,” he added, “would one find a Prime Minister inviting advice from abroad?”

The group then flew south to Chongqing, where they boarded the ship for the weeklong conference, organized primarily by the World Bank official Edwin Lim. They gathered in the boat’s main hall for the opening remarks by the octogenarian Xue. A party stalwart, Xue declared to the company of foreigners, whose presence would have been unthinkable only a decade before, “We are investing great hopes in this conference.”

Excitement ran high when Tobin took the floor for his presentation. Tobin was a genial, soft-spoken figure with a crooked grin—and a natural teacher, whether at Yale or on the Yangtze. The Chinese listened attentively as he delivered a crash course on monetary policy, outlining how governments manage aggregate demand and describing how they could make stable fiscal and monetary policy. In the middle of his lecture, Tobin pulled out a sheet of statistics. China’s economy was indeed overheating, Tobin said, and inflation had to be brought below seven percent as soon as possible. The Chinese were astonished at the speed with which Tobin came up with such a concrete recommendation.

China’s rulers wanted the country to get rich, but not at the cost of control.

As the ship chugged along, Kornai moved to the presenter’s seat. The Hungarian had won international fame for his critique of socialist economics in Economics of Shortage, published in 1980, a book that began with the simple facts of life in socialist countries around the world: empty grocery shelves, just a few styles of clothing, and lengthy queues at every store. Kornai argued that chronic shortages were the inevitable result of economic planning under traditional socialism. Chinese economists recognized what they saw in the Hungarian scholar’s prose and equations: these were China’s miseries, too.

Kornai’s topic was “Could Western policy instruments . . . be effective in socialist economies?” But hearing the Chinese say that they did not yet have a goal in mind for their reforms, he decided to answer a far larger question: What path should China take? Kornai argued that the experiences of failed transitions from socialism around the world suggested that China should pursue market coordination with macroeconomic control. He sketched out this model and its alternatives on a blackboard. Instead of seeking only to please cadres who had the authority to set quotas, forgive bad investments, and write off wasteful production, he argued, enterprises should respond to market pressures—competition would force them to improve their performance—but the state could still manage macroeconomic policy and regulate the economic and legal parameters of the market.

The other visiting economists agreed vigorously with the charismatic Hungarian, but the Chinese response was muted. Behind this composure, however, Kornai’s words resonated. One prominent Chinese economist, Wu Jinglian, later wrote that he had concluded that “a market with macroeconomic management should be the primary objective of China’s economic reforms.” That night, a group of Chinese economists excitedly approached Kornai and told him that they were determined to initiate an official Chinese translation of Economics of Shortage. Kornai spent the night sleepless in his cabin, exhilarated by the reception he had received.

THE YANGTZE CONSENSUS

On September 7, the Bashan pulled into the harbor at Wuhan, a port city in eastern China. Most of the group flew back to Beijing, and the Western economists returned home. Cairncross wrote in his diary, “I have no doubt that they consider what to do very carefully before deciding and do not necessarily accept advice.”

The Chinese participants prepared an internal report on the conference and sent it to Zhao and other top leaders. Zhao liked what he saw. Transcripts of internal party meetings show that later that month, he discussed the foreign experts’ suggestion that China focus on its inefficient enterprises as the key next step in the reforms. He even used Kornai’s analysis to highlight the problems of rapidly expanding investment in these enterprises.

As winter came to Beijing, the public report on the conference appeared in full. With detailed analyses of the ideas presented by Tobin, Kornai, and the others, the report revealed a group of Chinese reformers who were open to outside influence but understood the importance of reconciling foreign advice with the situation on the ground in China—and a Chinese leadership, with Zhao at the helm, that believed in the value of intellectual exchanges with the outside world.

It is far smarter to bet China’s future on openness than on isolation.

Yet not everyone was pleased. Party elders, aging but still filled with revolutionary zeal, lambasted the reformers in both internal meetings and public writings for “fawning on foreign theories,” in the words of a widely read editorial titled “Marxist Economics Has Great Vitality.” Zhao defended them, as party records leaked in the summer of 2016 show. Chastising a leading ideologue in 1986, he said, “You should be cautious when criticizing the liberalization of economic theory.”

Despite the attacks on his agenda, Zhao led reformers in a new drive to define the goal of China’s reforms as a system in which “the state manages the market, and the market guides the enterprises.” In 1987, with a series of policy documents released at the historic 13th Party Congress, Zhao succeeded, enshrining a central role for the once forbidden market in China’s future.

LET A HUNDRED FLOWERS BLOOM

Less than two years later, however, Zhao’s leadership came to a rapid end. In the spring of 1989, angry about pervasive corruption, persistent inequality, the lack of political reform, and skyrocketing inflation, students launched protests centered in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. Zhao opposed the government’s crackdown on the demonstrators, but this time, his views would lose out. Deng removed him from power in late May and placed him under house arrest. Sitting in the courtyard of what had become both his home and his prison, Zhao listened helplessly to the gunfire of the People’s Liberation Army as its soldiers fired on Chinese citizens on June 4, 1989.

Later that month, with order restored across the country, party leaders denounced Zhao. They pointed to his engagement with foreign economists as evidence of his alleged mission to push China to abandon socialism. Eliminating this pernicious influence would from then on require omitting any mention of both Zhao himself and the role of his many Western advisers. Today, his name almost never appears in print in China; the party takes credit for his achievements or attributes them to Deng.

In the 1990s, under the savvy technocrat Zhu Rongji, reforms took off and the economy boomed. The system that China built, a “socialist market economy,” was enshrined in the Chinese constitution in 1993, cementing the enduring mix of state and market that Zhao had embraced and developed. Zhu allowed the rapid growth of the private sector while maintaining state-owned enterprises, particularly in key industries such as energy, banking, and telecommunications, but he made Bashan-style reforms to those enterprises, downsizing them, eliminating some government subsidies, and limiting easy bank credit to failing firms, to force them to be more responsive to the market. He developed China’s financial system, created state-dominated stock markets, and overhauled the tax system. He increased the authority of China’s central bank so that it could conduct monetary policy as Tobin had encouraged in 1985. And Zhu led China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, a major milestone in China’s integration into the global economic system—and a powerful example of the influence of foreign economic ideas, since accession to the WTO required China to embrace a set of established international norms and practices. Indeed, Zhu used the pressure of these external norms to force much-needed domestic changes that had previously been politically untenable, such as increasing market competition with state-owned behemoths and opening up new sectors of the economy (from telecommunications to banking) to foreign financing.

Deng knew that instead of simply copying, China could adapt the best economic ideas from around the world to fit China’s distinctive context.

As skyscrapers sprouted up across Chinese cities and wealthy businessmen motored through the busy streets in sleek Audis and BMWs, China became an economic power with few equals. By 2010, China had overtaken Japan as the world’s second-largest economy in terms of GDP. China’s transformation consistently drew on ideas from far beyond its shores.

But the Chinese Communist Party tells a different story, one in which the system of economic organization that Zhao developed is stripped of his name and its international influences. Instead, the party describes China’s rise as a product of the party’s leadership and ingenuity, “grown out of the soil of China” (in the words of Foreign Minister Wang Yi). According to this narrative, only a self-reliant China can succeed in the face of a domineering West; the party’s narrative leaves little room for the truer story of a collaborative partnership.

Indeed, Xi has referred to “the competition with capitalism” and “the protracted nature of contest over the international order.” A party communiqué leaked as Xi came to power in 2013 warned that “the contest between infiltration and anti-infiltration efforts in the ideological sphere is as severe as ever, and . . . Western anti-China forces [will] continue to point the spearhead of Westernizing” China. In the economic sphere, this struggle is particularly acute, aiming “to change [the] country’s basic economic infrastructure and weaken the government’s control of the national economy.” This is not the language of a country that sees itself as happily integrated into the international economic order.

Western leaders should make clear that their Chinese counterparts risk more than they gain by shutting the door to outside influences. Western policymakers rightly criticize Xi’s militarism, mercantilism, and neglect of human rights and international norms. But people both outside and inside China should also tell a positive story of the rewards of openness, exemplified by the Bashan conference 30 years ago.

Deng knew that instead of simply copying, China could adapt the best economic ideas from around the world to fit China’s distinctive context. The engagement of the 1980s was not a sign of failure or submission to foreign hegemony but a signal achievement that powered China’s record-breaking economic growth. It helps explain why China’s transition from socialism, at least until now, has succeeded when so many other countries’ similar attempts have stumbled. And so it is all the more regrettable that China’s leaders today neither acknowledge nor seek to replicate the benefits of that era’s openness.

As a result, China risks missing out on the confidence-building effects of sustained, probing interactions about new ideas to solve China’s problems. Worst of all, by limiting the range of ideas from abroad that are permissible, it risks intensifying the chilling effect on economic thinking and policymaking at home, discouraging experimentation and innovation when it is most urgently needed to confront slowing growth, high debt levels, environmental deterioration, public disquiet, and a major demographic transition, among other challenges. Much of China’s future will turn on whether its leaders once again allow domestic and foreign ideas to mix freely.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions