The first half of the twentieth century witnessed some of the worst moments in modern history: two world wars, a global depression, tyranny, genocide. That happened largely because the Western great powers hunkered down in the face of economic and geopolitical crisis, turning inward and passing the buck, each hoping that it might somehow escape disaster. But there was nowhere to run or hide, and catastrophe swept over them regardless.

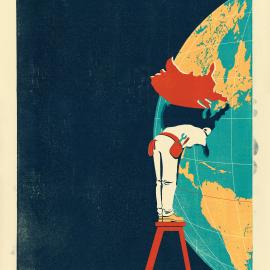

Reflecting on this afterward, Western policymakers swore not to repeat their mistakes and designed a postwar order based on mutually beneficial cooperation rather than self-interested competition. They recognized that foreign policy and international economics could be team sports rather than individual ones. So they linked their countries to one another in international institutions, trade agreements, and military alliances, betting that they would be stronger together. And they were correct: backed by extraordinary American power, the system they created has led to seven decades of progress, great-power peace, and economic growth.

So when Donald Trump chose “America First” as his presidential campaign’s foreign policy slogan, experts were appalled. Didn’t he realize that was the cry of pro-German isolationists who opposed American entry into World War II? Surely, embracing such a discredited position would hurt him, flying as it did in the face of everything U.S. foreign policy had stood for over generations. As usual these days, the experts’ predictions were wrong. But their reasoning was sound, because during his campaign, Trump did indeed offer a perspective on international politics closer to the nationalism and protectionism of the 1930s than to anything seen in the White House since 1945.

If the new administration tries to put this vision into practice, it will call into question the crucial role of the United States as the defender of the liberal international order as a whole, not just the country’s own national interests. At best, this will introduce damaging uncertainty into everything from international commerce to nuclear deterrence. At worst, it could cause other countries to lose faith in the order’s persistence and start to hedge their bets, distancing themselves from the United States, making side deals with China and Russia, and adopting beggar-thy-neighbor economic programs.

But governing is different from campaigning, and nobody knows yet just what the Trump administration’s actual foreign policy will involve. And as the authors in our lead package note, the liberal order has been fraying around the edges for years. As possible remedies, Richard Haass offers a new conception of order, Joseph Nye favors wiser leadership, Robin Niblett suggests refreshing liberal democracy, Michael Mazarr recommends institutional reform, Evan Feigenbaum advocates better ways of incorporating China, and Kori Schake warns of the dangers of U.S. retreat.

We are now officially living through interesting times; just how much of a curse that is remains to be seen.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions