President Donald Trump has made it clear that he believes the United States should consider using torture when interrogating terrorist suspects. Last February, during the Republican primary campaign, he pledged that if elected, he would authorize techniques “a hell of a lot worse than waterboarding.” Doing so, he later bragged, “wouldn’t bother me even a little bit.” Trump insisted that “torture works”—and that even if it doesn’t, terrorists “deserve it anyway.”

Soon after his inauguration, Trump indicated that in crafting policy on interrogations, he would defer to the counsel of his defense secretary, the retired Marine Corps general James Mattis, who opposes the use of torture. “I’m going with General Mattis,” Trump said in an interview with David Muir of ABC News. “But do I feel it works? Absolutely, I feel it works.”

The administration has continued to send mixed signals on the subject. In late January, The New York Times revealed the existence of a draft executive order that would have reversed the Obama administration’s 2009 decision to shutter the secret “black sites” where the CIA tortured detainees and to limit interrogators to the nonabusive techniques contained in the U.S. Army Field Manual. The Trump administration denied the Times’ report and soon circulated a different draft order on detainees, which did not call for such policy changes. But the episode left a distinct impression that although Mattis and other senior administration officials might oppose torture, Trump is hardly its only proponent in the White House.

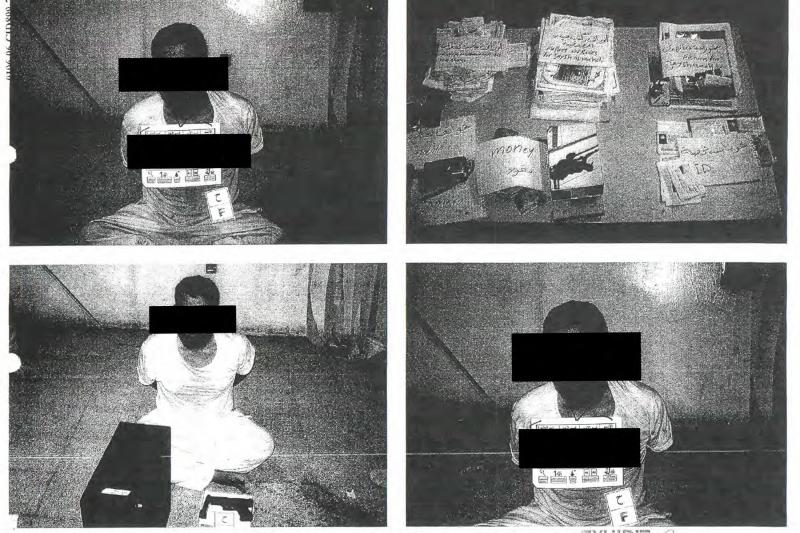

That torture is once again even a topic of discussion at the highest levels of the U.S. government is an alarming development for the country—and for us personally. One of us, Antonio Taguba, as a major general in the U.S. Army, authored a 2004 internal army report on prisoner abuse at the U.S. detention facility in Abu Ghraib, Iraq. Sifting through the evidence documenting the sickening ways that U.S. military personnel and contractors mistreated Iraqi detainees, he became intimately familiar with the very worst in human nature and the ugliness that war can produce in those waging it. And after what became known as “the Taguba report” was leaked and made headlines, everyone learned just how stubbornly the U.S. government can resist taking responsibility for its crimes and learning from its errors. The George W. Bush administration blamed the atrocities at Abu Ghraib on low-level troops and staffers, and the senior civilian and military leaders who devised and authorized abusive tactics and encouraged an environment of brutality escaped culpability. Later, the Obama administration declined to prosecute anyone for ordering abuse or participating in it, even though President Barack Obama had himself conceded that the United States had “tortured some folks.”

That torture is once again even a topic of discussion at the highest levels of the U.S. government is an alarming development for the country

That lack of accountability might be one reason why torture is back on the table and once again politically palatable. A 2014 Washington Post–ABC News poll found that a majority of Americans believed that the CIA’s use of torture was justified. And why wouldn’t they? By refusing to hold anyone responsible, Washington sent a clear signal to Americans that the abuse was, in fact, justified—even if it was illegal, immoral, and likely ineffective. But whether or not torture “worked,” there is little question that it harmed U.S. interests. As Douglas Johnson, Alberto Mora, and Averell Schmidt noted recently in this magazine:

Washington’s use of torture greatly damaged national security. It incited extremism in the Middle East, hindered cooperation with U.S. allies, exposed American officials to legal repercussions, undermined U.S. diplomacy, and offered a convenient justification for other governments to commit human rights abuses.

The wrong-headed policies that produced such high costs were developed by dozens of officials and implemented by a vast bureaucracy at a safe remove from the frontlines. But individuals had to actually carry them out. Two such people have recently published books reflecting on their experiences doing just that. Eric Fair was a contract interrogator for the U.S. Army in Iraq. His memoir, Consequence, is an act of confession, an effort to confront his demons. James Mitchell is a psychologist whom the CIA hired after the 9/11 attacks to help devise aggressive new means of extracting information from detainees. The book he co-authored with the former CIA spokesperson Bill Harlow, Enhanced Interrogation, is an act of self-defense. Mitchell, too, wants to confront his demons, which is how he seems to view almost anyone who has written critically about the abuse that he and others inflicted.

Taken together, the two books serve as a reminder of the importance of individual choice and personal agency, even in the expansive architecture of U.S. national security. If Trump wants to put the United States back into the torture business, he will need the compliance of individuals at many levels of government who are willing to break the law. At a debate during the Republican primary campaign last year, a moderator asked Trump what he would do if officials refused to torture detainees or to “take out their families,” as Trump had suggested might be necessary. “They’re not going to refuse me—believe me,” Trump scoffed. “If I say do it, they’re going to do it.”

We hope that Trump is wrong. To prevent a return to the darkest days of the so-called war on terror and the Iraq war, military officers, intelligence officials, enlisted people, and contractors must refuse to carry out any illegal orders they receive—even from the president himself. Doing so will serve the national interest and their own self-interest. For as these two books demonstrate—by design in Fair’s case and inadvertently in Mitchell’s—the damage wreaked by torture is not limited to the victims: it also extends to the souls of the torturers.

FOLLOWING ORDERS

Fair was born in 1972 and grew up a devout Presbyterian. He joined the army in 1995 and was honorably discharged in 2000. After the 9/11 attacks, he longed to serve his country once more and fight its new enemies. Although unable to put on the uniform again, he found a way to the war zone as a civilian contractor. Fair was hired by CACI, a U.S. corporation that had obtained a contract from the Defense Department to provide personnel for intelligence work in Iraq.

The company hired Fair as an interrogator even though he’d never received any military training in interrogation or intelligence analysis. His lack of experience was compounded, he claims, by the fact that prior to his arrival in Iraq in December 2003, CACI did not train him, either. But the company’s bare-bones orientation program did manage to convince Fair of one thing: the U.S. government had approved and authorized brutal interrogations. In a passage that every policymaker should read and remember, he writes: “We tortured people the right way, following the right procedures, and used the approved techniques. There are no legal consequences.”

Those sentences capture the ethos that guided many interrogators in the fight against terrorism, whether they worked for the military, the CIA, or civilian contractors. The result was an essentially rule-free zone in which interrogators were untethered from the usual restrictions on battlefield conduct. Fair’s description of near chaos inside interrogation rooms in Iraq matches what was learned during the investigation of the abuses at Abu Ghraib. Most military and civilian interrogators had received little more than on-the-job training and were not properly supervised. This left them confused about their responsibilities and, in some cases, uncertain about whether they were even subject to U.S. legal authority at all.

Officials must refuse to carry out any illegal orders they receive—even from the president himself.

In spare, haunting prose, Fair details his own conduct in this environment, which became more abusive over time. He recalls the first time he grabbed a detainee; his use of what his colleagues called “the Palestinian chair,” a technique they were told that Israeli interrogators use to force detainees into an excruciatingly painful position; and the way some detainees cried when he asked about their wives and families.

Inflicting agony on others took a toll on Fair. After he returned home, his marriage unraveled. He drank to excess. He believes he will never be able to earn redemption but that he is “obligated to try.” He was doing his country’s bidding; he was following orders. But what he did was wrong, and he still struggles to come to terms with his actions and find a way to make amends.

ROUGH MEN

Mitchell, in contrast, feels no guilt and seeks no forgiveness. He reminds readers that, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, justified fears of another assault drove U.S. policy, and the CIA saw coercive interrogations as one way to prevent more bloodshed. The agency turned to Mitchell and his colleague Bruce Jessen, who had served as psychologists in the U.S. Air Force and had overseen the Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) training program for personnel deemed to be at high risk of enemy capture. Mitchell and Jessen had designed and supervised some of the mock interrogations that SERE trainees undergo to prepare them for what they might endure should they ever fall into hostile hands. But the two men had never conducted genuine interrogations of enemy detainees. Nevertheless, they managed to convince the CIA that they could adapt SERE tactics to the real world, and they quickly became integral players in the CIA’s new detention and interrogation program. Over the next eight years, their company, Mitchell Jessen & Associates, reportedly earned some $81 million for its work. They are now facing a lawsuit filed in federal court in Washington State by two former CIA detainees and representatives of a third, who died in custody, accusing the psychologists of human rights violations and seeking compensatory and punitive damages.

Mitchell’s book brings to mind a quote of uncertain provenance that is sometimes attributed to Winston Churchill: “We sleep safely in our beds because rough men stand ready in the night to visit violence on those who would harm us.” Mitchell casts himself as a rough man and takes pride in the violence he visited on detainees such as the 9/11 plotter Khalid Sheik Mohammed, who was waterboarded 183 times. “I have looked into the eyes of the worst people on the planet,” Mitchell writes. “I have sat with them and felt their passion as they described what they see as their holy duty to destroy our way of life.” He and Jessen, he goes on, “did what we could to stop them.” Mitchell paints himself as something of a “good cop” in the interrogation room: his suggested techniques, he claims, were actually less brutal than “unproven and perhaps harsher techniques made up on the fly that could have been much worse.” Mitchell also asserts that his efforts produced intelligence that helped foil terrorist attacks and led to the capture or killing of high-profile targets, including Osama bin Laden.

The U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence spent five years and $40 million investigating such claims. Its 6,300-page report remains classified. But in 2014, the committee’s Democratic majority released a heavily redacted 500-page executive summary that refuted the idea that the torture carried out by Mitchell and others produced any particularly useful information. The executive summary also revealed that the CIA had routinely exaggerated the success of “enhanced interrogation” and that much of the intelligence the agency had gathered through torture was either incorrect or had actually been (or could have been) gleaned through other means.

It seems likely that the Trump era will test U.S. military and intelligence institutions and the individuals who bravely serve them.

Mitchell dismisses such findings and makes clear that he has no interest in handwringing about the moral or strategic costs of torture. At the end of his book, he writes that “Americans will not tolerate for long the reckless squandering of our freedoms to put ointment on some political leader’s conscience.” Like others who have spent their careers in the armed forces or the intelligence agencies, we have always sought to emulate military leaders of conscience, such as Dwight Eisenhower and George Marshall, and have looked to political leaders of conscience to act not only with wisdom and strategic sensibility but also with moral aptitude. But Mitchell seems to have a different understanding of the role of conscience in war and politics.

THE RULE OF LAW

In the aftermath of the Abu Ghraib revelations, investigations conducted by the U.S. Congress, government agencies, the U.S. military, human rights groups, and media organizations all pointed to the same conclusion: although the “war on terror” and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have differed in extraordinary ways from traditional armed conflicts, the laws of war must still apply. The Geneva Conventions of 1949; the UN Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhumane, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment of 1984; and the U.S. military’s Uniform Code of Military Justice were established to prevent atrocities. They are not fail-safe, and they are not perfect. But they are the law—as is the McCain-Feinstein amendment to the 2016 National Defense Authorization Act, which, among other things, made it illegal for U.S. personnel to employ interrogation techniques not explicitly authorized by the U.S. Army Field Manual. And regardless of what Trump might believe, no one is above the law, and no official can refuse to follow it—no matter what the president says. In the words of the U.S. Supreme Court justice Anthony Kennedy, “The Law is superior to the government, and it binds the government and all its officials to its precepts.”

It seems likely that the Trump era will test U.S. military and intelligence institutions and the individuals who bravely serve them. They can pass the test if they heed this simple advice: follow the law.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions