About 25 years ago, I spent a memorable afternoon in London with Michael Young, the author of the strange 1958 dystopian novel in the form of a dissertation called The Rise of the Meritocracy, which introduced that term into the English language. In the United States, for years, people have liked to insist that wherever they work or go to school is a meritocracy, meaning, roughly, that they understand it as an open competition in which the most deserving succeed. Americans assume meritocracy to be an unalloyed good; the term implies a contrast to some past system or an era when success went instead to lazy inheritors, timeservers, or adept players of office politics.

Young, however, wanted not to celebrate meritocracy but to warn the world against it. He had the detached air of someone who has quietly noticed everything, and a sense of humor so bone-dry that most people missed it. By the time I met him, he was Baron Young of Dartington—an oft-noted irony. But intellectually, he was a creature of the post–World War II British Labour Party, in which he served as an important adviser on education, and of the impoverished East End, where he did his sociological research. He had been involved in the great expansion of the state-run school system after the war, which was an aspect of the broader socialist project aimed at creating structured mass opportunity for the first time in British history. It was in keeping with the tenor of the time that this effort relied on administering intelligence tests to masses of 11-year-olds, who were then each directed into what was, essentially, a blue-collar or a white-collar educational track and who would, when they were a few years older, take another set of exams that would anoint a small cohort as bound for higher education.

In Markovits’s maximally bleak view, meritocracy has ruined American life.

Young assumed that this would be a fair system—that what the tests measured was “merit,” something crucial and immutable. But its results forced him to confront the question of whether there was any real moral difference between the new, deserving upper class and the older, undeserving one. He concluded that meritocracy functioned as a justification for a new and especially harsh class system and that therefore he preferred the old elite. As a socialist, his primary commitment was not to equal opportunity but to just plain equality, and he foresaw that what he had decided to call “meritocracy” would make equality harder to sell, since it would provide a supposedly scientific justification for inequality. “To be good, a society must have a fault,” he told me. The United Kingdom’s fault was a class system based on inheritance, which made the country a propitious environment for midcentury Labour socialism; the new meritocracy that Labour was creating would be much less propitious. The Rise of the Meritocracy ends by telling us that its author, a scholar named Michael Young, has regrettably been killed in a bloody mass uprising against the meritocrats.

In the current moment of global populist, nationalist, and socialist revolts against elites, this scenario seems prescient. And yet in his new book, The Meritocracy Trap, the legal scholar Daniel Markovits rather ungenerously insists that “Young’s satire missed its mark by a mile.” By that, Markovits means two things: that Young failed to understand that meritocracy is itself actually based on the circumstances of birth rather than merit, and that his idea that meritocracy was something to be avoided, not embraced, never caught on. Quite the reverse happened: in Markovits’s maximally bleak view, meritocracy has ruined American life. By presenting itself as a means of providing equal opportunity, it has preemptively shut down opposition; it pushes inequality to ever-higher levels; it serves as an efficient mechanism for the inheritance, rather than the upending, of privilege; and it turns even its relatively small number of beneficiaries into miserable, relentlessly pressured workaholics who have to expend most of their large incomes on their children’s private schools and tutors. Markovits’s picture of American society is so lurid, so inexorably dark, that it invites skepticism more than it persuades.

CASTE OF CHARACTERS

Young was sort of kidding about the threat meritocracy posed. Markovits most definitely is not. He attributes to meritocracy a very high level of social and economic damage—maybe not on a level with what Soviet communism wreaked in Russia, but not entirely out of that range. The charge can’t be evaluated without first defining “meritocracy” precisely, which isn’t so easy.

Like all social systems, the one that Markovits describes was made and not born. His righteous rage against it is powered by a sense of betrayal, or promises unkept: as he puts it, “Despite the motives that led to its adoption, meritocracy no longer promotes equality of social and economic opportunity, as it was intended and expected to do.” But historically, it was neither intended nor expected to do that. The founders of the system Markovits’s book examines did not have the word “meritocracy” available to them, because Young hadn’t yet written his book at the time when they were devising it. They also did not think they were addressing the problem of opportunity in the United States. The British Education Act of 1944 was aimed at expanding the state-run educational system. The American meritocracy, launched at roughly the same time, had a narrower purpose: to use IQ tests as an admission device for elite undergraduate institutions, as a way of changing the character of those schools and creating a new breed of high-level technocrats.

If the system had a father, it was James Bryant Conant, the president of Harvard University from 1933 to 1953, whom Markovits mentions only in passing. It was Conant who arranged for the SAT, an adapted IQ test, to become the dominant college admission device. While he was doing this, in stages during his reign at Harvard, he was also occasionally writing essays calling for the establishment of a new, classless America. But it’s worth noting that during his peak period of influence, he was also a leading opponent of the GI Bill, the greatest expansion of educational opportunity the country had ever seen. Historical figures act according to the assumptions and exigencies of the moment; Conant was focused on promoting the research university model at Harvard and other elite academic institutions and on winning the Cold War. The prospect of wasted scientific and administrative talent haunted him, and he feared that class divisions would weaken American society.

Many assume that Ivy League degrees are tickets to status and success.

His solution to these problems was to create large but strictly tracked public high schools whose male graduates would also have to go through a period of compulsory national service. If everybody went to high school and did their national service together, he believed, that would prevent class tensions from developing, so the project of strict elite selection could proceed unimpeded. Expanding access to college was not part of his plan; doing so would have diluted the focus on superachievers that Conant thought universities should maintain. He also expected that the new American elites would be overwhelmingly oriented toward public service, as were graduates of top universities in Europe, and that they would not try to rig the system that had produced them in order to advantage their children. Those qualities, too, would forestall any resentment the new elites might engender.

Like most social visionaries, Conant was substantially wrong in his expectations about the system he was helping create—especially about how it would be perceived by the public. Today, many people assume that admission to Ivy League schools is a process that is highly susceptible to corruption by prosperous parents, and degrees from those institutions are widely perceived as tickets to gaudy status and material success, not to careers in public service. This is partly, but not entirely, accurate. Ivy League admissions now rely on a pastiche: remnants of the pre-Conant system—preferences for athletes and the children of alumni, for example—persist alongside a genuine commitment to racial and class diversity, as well as the strong emphasis on academic criteria that Conant wanted. And Ivy League students are inculcated into an elite culture defined less by crass ambition than by a peculiar mixture of soaring liberal idealism and an overwhelming preoccupation with success.

Markovits’s home institution, Yale Law School, is an exemplar. It was founded in 1824 but essentially refounded in the late 1920s, when a coterie of fiery young reformers led by the legal scholar and future Supreme Court justice William Douglas arrived after defecting from Columbia University and gave the school a decidedly more liberal cast than its competitors. Yale still overproduces law professors, judges, and government officials. It is also intensely conscious of being considered the country’s number one law school. Its students have run a brutally competitive academic gauntlet for two decades before they arrive, and when they leave, they are highly attractive to prominent commercial law firms. The Meritocracy Trap grew out of a speech Markovits gave at the Yale Law School graduation ceremony in 2015, which he began by assuring his listeners of their preeminence. “You are sitting here today because you ranked among the top three-tenths of one percent of a massive, meritocratic competition,” he said, “in which all the competitors conspicuously agree about which is the biggest prize.” But the system that produced them, he added, had been “a catastrophe for our broader society.” This blending of status consciousness and stinging social critique is deeply woven into the fabric of the institution.

The story Markovits tells isn’t so different from the one that Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray laid out, controversially, in The Bell Curve in 1994, except that Markovits vigorously insists that the special qualities of meritocrats result from their upbringing and their own efforts rather than from inherited traits. But in both versions of this tale, there existed a baseline period, before SAT-based admissions, when Ivy League students were not especially bright and when, conversely, potential meritocrats were scattered randomly across the class system. Then came a dramatic change in admission policies at elite universities, which led to the displacement of the old American upper class by a new, more deserving one. The resulting meritocratic elite efficiently replicates itself through campus-based “assortative mating,” ruthless residential and social self-segregation, and high-pressure child-rearing practices. Therefore, Markovits writes, “American meritocracy has become precisely what it was invented to combat: a mechanism for the concentration and dynastic transmission of wealth, privilege, and caste across generations.”

The consequences of these developments, in Markovits’s account, are even worse than the plain fact of an aristocracy-to-meritocracy-to-aristocracy dynamic would indicate. The old aristocracy presided over a “classless society,” he writes, a near paradise of middle-class prosperity and opportunity. The new meritocrats, who on graduation quickly become extravagantly paid “superordinate workers” in fields such as finance and law, have created “a stagnant, depleted, and shrinking world” for the middle class by redefining economic value in terms that reward the kinds of labor only they, the meritocrats, perform and by pulling an increasing proportion of all economic activity into their purview and away from everyone else’s.

To Markovits, because of what the meritocrats have done to American society, there is hardly any difference these days between the middle class and the poor: “Meritocracy remakes the middle class as a lumpenproletariat.” The United States now features a bipolar labor market, “epitomized by Walmart greeters and Goldman Sachs bankers.” And the meritocrats don’t even get to enjoy feasting on the carrion of the good society they have ruined, because they are working too hard: “A brilliant vortex of training, skill, industry, and income holds elites in thrall, bending them from earliest childhood through retirement to an unrelenting discipline of meritocratic production that alienates superordinate workers from their labor, so that they exploit rather than fulfill themselves and eventually lose authentic ambitions that they might never fulfill.” A meritocrat can’t go into “teaching, . . . or journalism, public service, or even engineering,” because to do so would mean “sacrificing her own, and her children’s, caste.”

THE BAD OLD DAYS?

Markovits is hardly the first writer to notice that inequality is rising and middle-class incomes are stagnating in the United States. What’s distinctive about his argument is the direct causal link he draws between a change in the admission policies of a handful of elite universities and, a few decades later, a tableau of vast, nearly hopeless social and economic ruin. He regularly makes the connection simply by using the phrase “meritocratic inequality” as a synonym for “inequality.” That certainly gets the reader’s attention, but it’s also highly tendentious.

The first problem with Markovits’s version of the world is that the pre-meritocratic society he conjures up is more a projection than a rigorously established historical fact. He asserts that in an earlier era, the elites were “dull, sluggish, and inert” people who didn’t work hard—“lazy rentiers who deployed inherited wealth and power to exploit subordinate labor.” The top universities they attended were characterized by “uncompetitive mediocrity.” Their education “had no compelling purpose.” These are pleasing thoughts if one happens to be a meritocrat, but they are very difficult to prove, partly because pre-meritocrats were not evaluated with standardized tests. American popular culture in the pre-meritocracy period was full of hagiographies of economic titans, but they were self-made industrialists, not landed gentry: Andrew Carnegie, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford. Even more plausibly aristocratic (but hardly lazy) types, such as Henry Adams and Edith Wharton, were exquisitely aware by the early twentieth century that their class’s preeminence was being threatened by uncouth people with newly acquired fortunes not based on landownership. And universities such as Harvard, Princeton, and Yale were already well on their way to being considered among the best in the world, decades before they had altered their admission policies.

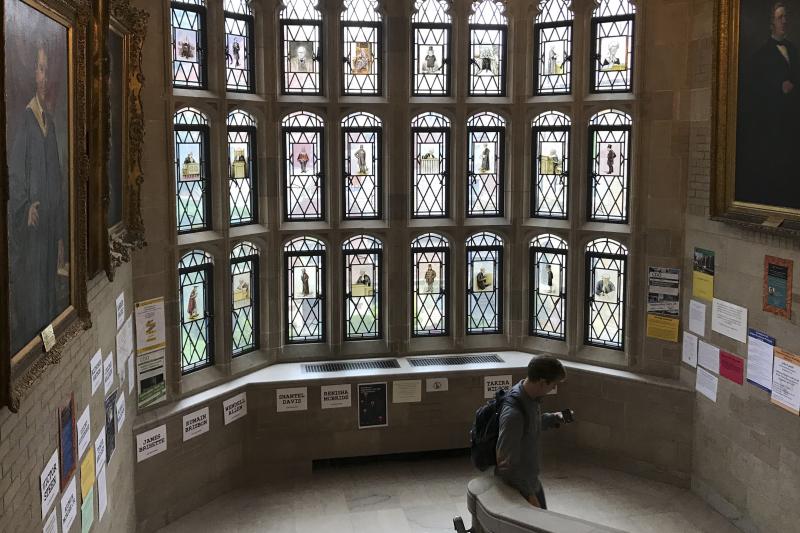

A better way of thinking about the change in Ivy League admissions is as a chapter—and not one with “no historical precedent,” as Markovits claims—in the never-ending recalibration of the membership criteria for this particular corner of the American elite. Owen Johnson’s 1912 young-adult novel, Stover at Yale, a bible of sorts for generations of Old Blues, depicts a fanatically competitive college culture but with a narrow group of participants and a set of standards that attributed much less importance to academic achievement than to factors such as “character” and “leadership,” which were hard to define but nonetheless palpable to the students at the time. Kingman Brewster, Jr., the president of Yale for most of the 1960s and 1970s, whom Markovits credits with bringing meritocracy to the university, dialed up the importance of academic criteria and tried to include groups such as African Americans and women but didn’t entirely scrap the old system, either. Brewster used to say that the alternative to the changes he was pushing was that Yale would become merely “a finishing school on Long Island Sound”—meaning that he was preserving its importance, not remaking the entire U.S. political economy and opportunity structure.

FINAL GRADE: INCOMPLETE

The Meritocracy Trap gives the impression that today, the superprosperous one percent is essentially conterminous with the new class of Ivy League graduates and that all of them face the kinds of punishing work schedules maintained by Markovits’s former students who bill 2,000 hours a year at white-shoe law firms. They dominate the business world. Their money and status are a reward for their superiority—“no prior elite has ever been as capable or as industrious as the meritocratic elite”—and therefore, “to deny that meritocrats earn and deserve their income seems to require denying that anyone ever earns or deserves anything.”

A theory is supposed to be predictive and testable, but Markovits often falls into the post hoc fallacy when presenting evidence for his: if anybody does anything amazingly productive, it must mean that person is a meritocrat, regardless of his or her educational background. He claims, for example, that “the cascading innovations behind the managerial revolution did not arise spontaneously. Instead, they were all—every one—generated from within meritocracy, by . . . workers coming out of America’s newly meritocratic schools and universities.” Because his meritocrats apply their nearly superhuman talent and resources to the fullest extent to raising their children in a meritocratic hothouse, whatever they have, the next generation will surely have, too.

The mind teems with objections to these extravagant assertions. Aren’t there any members of the one percent who inherited their money, or who started their own businesses, or who invest for a living? Aren’t there people who work at the Wall Street and Big Law bastions that Markovits identifies with meritocracy who didn’t go to Ivy League schools? What about people whose main compensation does not take the form of salaries based on hours worked (which is how Markovits suggests that all meritocrats are paid) and instead consists of bonuses based on measurable economic performance—traders, fund managers, and the like? What about meritocrats who have somehow managed to do something they enjoy that doesn’t pay boatloads of money? What about meritocrats whose children go to college but not to Ivy League schools? Readers of The Meritocracy Trap might be surprised to learn that 65 percent of Yale’s current sophomore class went to public school and that only 11 percent were admitted owing to a “legacy affiliation,” such as being the child of an alumnus.

Outside the tight confines of elite education, the broader social order that Markovits calls “meritocracy” comprises three distinct concepts that he lumps together: equality (that is, how evenly distributed income and wealth are), mass mobility (whether conditions are improving for the whole society), and circulation mobility (how efficiently socioeconomic status is passed on from parents to children). It’s possible that changes in elite college admissions would affect none of those, because the numbers involved are too small to move the needle in a country of more than 325 million people. Other possible causes of the “great compression” of income inequality during the third quarter of the twentieth century include high marginal tax rates on the rich, widespread unionization, and a heavily regulated economy that made what is now called “disruption” difficult. During that period, mass mobility was driven by a growing economy and a substantial expansion in access to higher education, mainly in the relatively unselective public universities that the great majority of U.S. students attend. Circulation mobility in the United States, contrary to American mythology, has never been appreciably higher than in Europe, and it hasn’t changed much over the years.

OUTSIDE THE IVORY TOWER

If one believes that the overall social and economic conditions of the United States have been produced by meritocracy, then it’s natural to look to meritocracy as the zone where reforms should take place. Markovits proposes to solve the larger problems of the country by taking away private universities’ tax deductions unless they draw half their students from the bottom two-thirds of the income distribution; he believes this would force them to expand their enrollment. The narrowness of this remedy is a sign of how little space the nonelite, non-university world takes up in Markovits’s vision. There is very little politics or economics or history in The Meritocracy Trap—only the cascading effects of changes in elite college admissions, which explain practically everything.

Even within higher education, Markovits’s scope is strikingly limited. Public universities, plagued by low graduation rates and large cuts in funding, might be a plausible place to look if one wants to enhance opportunity and promote equality, but they are hardly mentioned in the book. “The thought that a generic BA constitutes a general ticket of admission into the elite is . . . a midcentury idea,” Markovits writes dismissively. But the data clearly show that getting any college degree meaningfully improves one’s life chances and that the difference in value between an elite degree and a “generic BA” is less than most upper-middle-class parents probably believe. Anyway, isn’t shoring up the middle class, rather than providing access to membership in the elite, Markovits’s larger mission?

Most of the possible solutions to rising inequality don’t involve meritocracy at all.

Rising inequality and the stalled progress of the middle class are the preoccupying problems of American society today, and most of the possible solutions offered by politicians, intellectuals, academics, and activists don’t involve meritocracy at all. Markovits suggests changes in the notoriously regressive payroll tax and redistributing work in ways that support “mid-skilled production.” But these fall far short of the grand effort, on the scale of the New Deal, that he plausibly insists would be necessary to address the situation successfully. Because he is so focused on selling the distinctiveness of his approach, he tends to ignore or underrate the many other possible remedies that are part of the national conversation right now. These include enhanced antitrust policies (a concentration of economic power and inequality go together), wealth taxes, higher income tax rates in the top brackets, and significant enhancements to the basic welfare-state package of public education, health care, and old-age pensions. Ninety percent of young American adults now go to college, but their completion rates are parlously low—60 percent for those pursuing a bachelor’s degree and 30 percent for those pursuing an associate’s degree at a community college. Both those degrees are strongly correlated with higher lifetime incomes and lower unemployment rates. Enhancing teaching and advising so as to improve college completion rates would be a good way to expand opportunities for most Americans.

Works of social diagnosis and prescription are always produced from within a particular time and place and culture. Some of them wind up looking like trenchant analysis, and others like documents that vividly expose the world from which they emerged. The Meritocracy Trap seems destined to wind up in the latter category. It displays a brilliant mind choosing to understand a great global turn toward market ideology and policy as the product of changes at a handful of elite universities. That’s a sign of how unconsciously constrained the view from those places can be.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions