FOREIGN POLICY NEEDS A ROAD MAP

Francis J. Gavin and James B. Steinberg

Daniel Drezner, Ronald Krebs, and Randall Schweller (“The End of Grand Strategy,” May/June 2020) are surely right that grand strategy is challenging, particularly in a world characterized by a diffusion of power, a changing and multidimensional international system, political polarization, populism, and distrust of elites. They are profoundly wrong, however, in arguing that those factors make grand strategy irrelevant or even counterproductive for the United States today. On the contrary, it is precisely because the world is so complex and challenging that grand strategy is more important than ever.

A strategy is a way to relate a choice of means to one’s goals, and it’s hard to argue that policymakers don’t need that: after all, that’s what policy is all about. To paraphrase Lewis Carroll, if you don’t know where you want to go, every road is as good as the next. But the corollary is equally important: once you do know where you want to go, some roads are better than others. What makes grand strategy, as opposed to mere strategy—and as opposed to the incrementalism and decentralization that Drezner, Krebs, and Schweller propose—essential to policymakers is that they face competing short- and long-term goals and multiple, often crosscutting challenges. Grand strategy allows policymakers to integrate their efforts to pursue these objectives simultaneously and to adjudicate among them when they appear to be in conflict. A grand strategy is a map of the forest that allows policymakers to find the path home through the trees.

Grand strategy not only allows policymakers to prioritize and accommodate divergent ends; it is also vital in the choice of means. In its most simplified form, policymaking rests on the assertion that if a country adopts policy X, it will achieve goal Y. But even in the best circumstances, with the most conscientious policymaking process and decision-makers, the relationship between a proposed policy and the desired outcome is inherently uncertain. No new foreign policy challenge is the same as one seen before, and unlike scientists, policymakers do not have the luxury of testing out a variety of approaches to see what works best; they need decisional rules that allow them to make principled choices among competing options.

Consider the United States’ never-ending debate about NATO enlargement. Proponents of enlargement have based their argument in part on the view that the United States would be more secure in a world where countries are able to make choices free from the coercion of great powers. Critics, on the other hand, have contended that maintaining good relations with major powers is vital to securing U.S. interests, even if that means according each of those powers a sphere of influence in its neighborhood. Which approach should the United States adopt? Drezner, Krebs, and Schweller believe that Washington should “decentralize authority and responsibility.” But on what basis could an individual NATO commander or special envoy pick between these competing perspectives? Only grand strategy provides the criteria to help choose between these two plausible but incompatible views about how the world works and how that understanding should inform policy choices. Why, especially in a democracy, should that choice be delegated to a military officer or a midlevel unelected official?

Drezner, Krebs, and Schweller observe that the global problems the United States faces are often nonlinear. That very insight further buttresses the need for a grand strategy. The world has seen moments when an unforeseen event triggered profound change, such as the July Crisis of 1914, which led to World War I; the political revolutions of 1989–91; and the 9/11 attacks. A policy based on incrementalism and decentralization is precisely the wrong approach when such profound changes occur. Consider U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s masterful approach to fascism in Europe and the breakdown of the international economic order in the wake of the Great Depression. Despite entrenched isolationism and populist xenophobia in the United States, Roosevelt understood that the country’s peace and prosperity depended on deeper international engagement. The measures he pursued may have seemed incremental, but they were guided by a grand strategy that dramatically transformed the United States’ role in the world and laid the groundwork for a new postwar order. In the absence of such a clear and bold long-term strategy, it is doubtful that Roosevelt could have surmounted the domestic and international obstacles that favored caution and inertia.

TUNING THE ORCHESTRA

The authors also point to the waning capacity of big powers to influence the global landscape and the declining role of military and economic power. But these changes, too, only deepen the need to integrate all elements of national power to achieve national goals: the tougher the problems, the less effective ad hoc responses will be. Nothing illustrates the point better than the Trump administration’s fitful, scattered, and incremental response to the COVID-19 crisis. An effective grand strategy would allow the government to recognize profound global changes and respond to them in a coordinated, consequential, and effective way.

But grand strategy does more than provide coherence to the disparate strands of national policy. It helps communicate the interests and goals of the United States to many audiences, including its own officials, allies, and adversaries. It allows the entire government bureaucracy to sing from the same page by offering an anthem to officials to guide their day-to-day work—especially those who fill positions below the level of the president and the cabinet but who still play a critical role in pursuing national interests. Drezner, Krebs, and Schweller advocate decentralizing policymaking. They are right to stress the importance of “appreciating regional knowledge” and to warn against the dangers of conducting policy from 5,000 miles away. But how can “theater commanders, special envoys, and subject-matter experts” possibly know what fundamental choices to make in the absence of an agreed-on grand strategy? If U.S. Central Command received a request to support Saudi Arabia in its proxy war in Yemen, for example, how would it decide between reassuring a key ally and the risks of contributing to a deepening humanitarian disaster?

Grand strategy allows the entire government bureaucracy to sing from the same page.

U.S. policy toward Iran is a case in point. It goes without saying that the United States has multiple interests at stake: preventing Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons and countering its destabilizing policies in the Middle East, first and foremost, but also maintaining effective working relationships with key European allies, strengthening multilateral institutions such as the International Atomic Energy Agency, and showing solidarity with people fighting for human dignity and a voice in their own governance. How, absent some broad grand strategic framework, can American decision-makers sort through this tangle of interests and produce policies that are consistent and integrated rather than pulling in opposite directions?

The executive branch is not the only audience for U.S. grand strategy. For Congress, grand strategy is a way to understand and assess what an administration hopes to achieve and how, thus facilitating the legislative branch’s critical involvement in the policymaking and policy-implementation process. It is for this very reason that Congress adopted the requirement that every presidential administration prepare a National Security Strategy.

Even more important, a grand strategy provides a conceptual platform for a broad, vigorous, and informed public debate about the United States’ role in the world, one based on a rich and inclusive discussion of basic principles and that goes beyond the ad hoc, reactive analysis of day-to-day policy decisions. Drezner, Krebs, and Schweller assert that grand strategy is more difficult in an age of populism. In fact, increased populism makes grand strategy more needed than ever. A grand strategy allows an administration to articulate an overarching framework, and that articulation lets the public participate meaningfully in the decision about where to steer the ship of state and how best to get there.

COMPOSING THE SCORE

The authors seem to forget that today is hardly the first time that a debate over U.S. foreign policy has taken place at a time of political polarization and popular mobilization. From the Founding Fathers’ divisions over the wisdom of the Jay Treaty of 1794 (a grand strategic debate if ever there was one), to the arguments over the Spanish-American War, to quarrels over how to respond to the communist revolution in China, U.S. foreign policy has been deeply entwined with domestic political passions and partisan fights. Even within parties, consensus has often been elusive: witness the contest between the Cold War grand strategy favored by President Richard Nixon and that preferred by President Ronald Reagan. Nor is populism or distrust of elites new. As the historian Richard Hofstadter argued in his seminal 1964 essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” since the early days of the United States’ founding, “American politics has often been an arena for angry minds.”

Grand strategy has never been easy. As U.S. secretary of state under President James Monroe, John Quincy Adams faced daunting challenges. The United States had just emerged from the War of 1812, which had ended in a stalemate and had exposed political fissures that nearly tore the country apart. The United States was weak. Countries and empires stronger than it sought to craft a world order inimical to American interests and values. And the Industrial Revolution unleashed powerful global forces that upended the rules of politics and power. This political division, combined with postwar economic malaise and increased immigration from Europe, gave rise to powerful populist forces, represented most clearly in the form of General Andrew Jackson, and a deepening sense of national disunity. Elites and institutions were distrusted, and the proliferation of hyperpartisan newspapers created a media landscape riven by suspicion and disinformation.

Adams, operating under severe constraints, crafted an approach that preserved his country’s freedom of action, laid the groundwork for expansion, and skillfully managed European powers that might have threatened the young republic. Steeped in American values and marked by a sharp understanding of U.S. interests, Adams’s vision laid the foundation for the United States’ long-term security and prosperity, managing the short-term perils in a way that set the stage for the country’s global emergence a century later. It is precisely this kind of thoughtful grand strategic vision that the United States desperately needs today.

DREZNER, KREBS, AND SCHWELLER REPLY

We appreciate Francis Gavin and James Steinberg’s vigorous response. And we share their admiration for grand strategy’s theoretical virtues. In our professional lives, each of us has at times happily played the armchair grand strategist. In our writing and teaching, we have taken presidents to task for lacking a grand strategy or for failing to pursue one consistently. Like so many others in our circle, we have grieved for grand strategy: denying its growing irrelevance, expressing anger at decision-makers for their poor choices, proposing possible bargains to resuscitate a coherent grand strategy, and feeling depressed over the loss. But unlike Gavin and Steinberg, we have finally moved on to the final stage of grief: acceptance.

Gavin and Steinberg stress the promise of grand strategy without acknowledging the possible pitfalls. They know full well that the United States has, more often than not, fallen short of their theoretical standard. The White House’s strategy documents typically avoid prioritizing clearly among “competing short- and long-term goals and multiple, often crosscutting challenges,” as they put it. As a result, “the disparate strands of national policy” often lack the “coherence” that grand strategy can in principle bequeath. We would be heartened by the vision of an “entire government bureaucracy . . . sing[ing] from the same page” thanks to a grand strategic “anthem”—if we were not more often struck by the sheer cacophony emerging from the U.S. foreign policy apparatus. With reality so often at odds with their idealized portrait, Gavin and Steinberg retreat into exhortation. What is going on in Washington today, they declare, reveals why grand strategy is more important than ever.

In their full-throated praise of grand strategy, Gavin and Steinberg do not address the main question that animated our article: Why has the United States in recent years had such difficulty formulating and executing a competent grand strategy? Let us, for the moment, grant the validity of their examples of past grand strategic virtuosity. The fact remains that the current international and domestic challenges to an effective grand strategy are insurmountable. A world marked by nonpolarity, political polarization, radical pluralism, and populism is infertile ground for a viable and sustainable grand strategy.

Gavin and Steinberg do not deny that the obstacles to an effective grand strategy are greater than ever. Nor do they explain how U.S. decision-makers can or will overcome such obstacles. Nostalgic for past foreign policy successes, they seem committed to preserving the myth of grand strategy in the absence of its reality.

Gavin and Steinberg seem committed to preserving the myth of grand strategy in the absence of its reality.

To that end, they offer the reader a cherry-picked list of grand strategic successes, while conveniently overlooking the failures. Committing to a grand strategy can be costly, especially in times of radical uncertainty. Gavin and Steinberg rightly cite the July Crisis of 1914 and the 9/11 attacks as such “moments when an unforeseen event triggered profound change.” But were the European powers served well by the grand strategies that led them into World War I? Was the United States served well by its post-9/11 grand strategy, which produced the global war on terrorism and the Iraq war? Given the results, we cannot agree that “a policy based on incrementalism and decentralization is precisely the wrong approach when such profound changes occur.” During those critical junctures, a more incremental policy might have prevented those tragic errors.

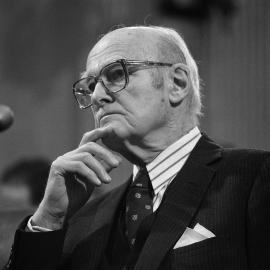

Indeed, many of the past successes cited by Gavin and Steinberg derived less from the rigorous pursuit of a grand strategy than from improvisational leadership. They approvingly cite Franklin Roosevelt’s “clear and bold long-term strategy” that “dramatically transformed the United States’ role in the world.” Yet Roosevelt was not a linear thinker who developed and then consistently followed a grand strategy. He was, in the historian Warren Kimball’s apt image, a “juggler,” who adapted and improvised in response to events. U.S. foreign policy in the early Cold War was a triumph, but it did not spring fully formed from the heads of thinkers such as George Kennan or Paul Nitze. It emerged in a piecemeal fashion and appears as a coherent strategy only in retrospect. And the George H. W. Bush administration brilliantly managed the end of the Cold War by jettisoning strategic commitments and moving forward experimentally into the unknown.

The lessons of this track record are clear. National decision-makers, obliged to make choices in an open, dynamic, nonlinear system that is rarely in equilibrium, should act incrementally and learn from trial and error. They should not be straitjacketed by grand strategy, an idea whose time has passed. It gives us no joy to arrive at this conclusion, but we see no reason to continue investing in an illusion.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions