“A man is not deceived by others; he deceives himself.” This quotation, from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, serves as the fitting epigraph to Robert Draper’s riveting new book on U.S. President George W. Bush’s decision to go to war in Iraq. In contrast to most accounts of the decision-making process that led to the invasion in March 2003, To Start a War stresses that the president himself was the decider—not Dick Cheney, the vice president; not Donald Rumsfeld, the secretary of defense; not Paul Wolfowitz, the deputy secretary of defense; not Scooter Libby, the vice president’s chief of staff. Moreover, Draper clarifies that Iraq was not the administration’s obsessive preoccupation from the very beginning. The surprise attack on 9/11 changed the president’s calculus, creating a direct line from that tragic event to the even more tragic decision to invade Iraq. Bush frequently insisted that he had not yet made up his mind, but Draper claims that he was deceiving himself. “In truth, Bush had stacked his own deck,” Draper writes. “Prizing loyalty above all else, he had surrounded himself with subordinates who believed that their job was to support the president’s value judgments rather than to question them.”

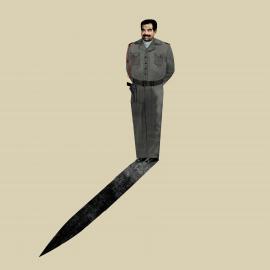

Bush’s vision, moreover, was clear, Draper argues: “to liberate a tormented people,” “to end a tyrant’s regime.” The president should have known that Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s dictator, had no weapons of mass destruction (WMD), no links to al Qaeda, and no responsibility for 9/11. According to Draper, Bush led the United States into a needless war. He did so because he believed deeply in the United States’ nobility and its mission to spread freedom—which Draper says the president considered “God’s gift to the world.” Not only was Saddam “the guy who tried to kill my dad,” as Bush once noted, referring to a failed plot to assassinate George H. W. Bush in 1993. Far worse, the president said, “he hates the fact, like al Qaeda does, that we love freedom.” These, according to Draper, were Bush’s animating impulses.

No policymaker comes off well in Draper’s account. From the moment he took office, Cheney worried about the United States’ vulnerability to terrorists armed with chemical or biological weapons. “After 9/11,” Draper writes, the Office of the Vice President “emerged as the Bush administration’s think tank of the unthinkable, where apocalyptic scenarios became objects of obsession, no matter how unlikely.” Whereas Cheney was quiet, thoughtful, and probing, Rumsfeld was an irascible, irresponsible bully. He schemed to get close to Bush, collaborated with Cheney, and sidelined civilian subordinates and military officers who disagreed with him, thereby ensuring that “dissent on critical issues was close to nonexistent in the Pentagon.” Secretary of State Colin Powell, in Draper’s view, had deep-seated reservations about going to war but lacked the courage to voice his convictions and did not possess an alternative vision that he could sell to the president. He carefully guarded his doubts lest he become irrelevant. George Tenet, the director of the CIA, prized the attention that Bush bestowed on his agency and massaged the information going to the president for fear that he would be perceived as soft. Many of Tenet’s subordinates assumed that their boss did not want to antagonize “the First Customer,” the president, and hence hesitated to convey many of their reservations about the accuracy of their assessments of Iraq’s WMD programs. Among this set of feuding, distrustful advisers, all of whom had had years of experience in the highest echelons of past administrations, Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s national security adviser, was outmatched and unable to orchestrate the consensus recommendations for which she yearned.

If all of this sounds familiar, it is. But Draper develops his arguments with an astonishing amount of detail, stemming from extensive interviews he conducted with Wolfowitz, Powell, Rice, Richard Armitage (Powell’s deputy), Stephen Hadley (Rice’s deputy), Douglas Feith (the undersecretary of defense for policy), and Eric Edelman (an adviser to Libby)—along with many other key officials in the State Department, the Pentagon, and the White House. Even more illuminating is the information he gleaned from talking to roughly 70 analysts, station chiefs, and middle- and upper-level managers in the CIA. From these interviews, Draper presents a devastating indictment of the way a key document making the case for war was created. The National Intelligence Estimate on Iraq’s WMD, designed in October 2002 to satisfy skeptics in Congress, drew on unreliable sources and came to exaggerated conclusions based on a “tissue-thin foundation of facts.” Draper offers an even more appalling account of the scripting of Powell’s address to the UN Security Council in early February 2003. The speech insisted that Iraq had failed to disarm, but the analysts and policymakers who contributed to it ignored mounting evidence that their information about Iraq’s weapons programs was flimsy at best. Perhaps even more consequential is Draper’s analysis of the inadequate and chaotic planning for the postwar occupation of Iraq. He claims, for example, that when Defense Department officials decided to disband the entire Iraqi army, they did so without the knowledge of the president. It was a disastrous decision: the demobilization alienated many Iraqi military officers and drove them toward the emerging insurgency.

To Start a War will go a long way to solidify prevailing views about the dysfunction, naiveté, and dogmatism of Bush and his advisers. Draper is an influential journalist, with a wide network of sources throughout the intelligence and policymaking communities, and his 2007 book on Bush’s White House years was well received. Readers will come away convinced that the Bush administration was led by a self-confident, simplistic, and incurious president and advisers notable for their arrogance and irresponsibility. The hundreds and hundreds of footnotes Draper includes that cite his interviews and reference declassified documents convey an authenticity that must not be discounted. Yet one cannot help but wonder if his account is a simplification of reality.

SADDAM’S GAME

Most concerning is Draper’s portrayal of Saddam. At the end of the book, Draper questions whether there was “a shred of evidence” that he intended to harm the United States. “The megalomaniacal madman of the Bush administration’s collective imagination had . . . largely checked out of running Iraq’s affairs.” He was divorced from reality, delegating authority, writing fiction and poetry, and hoping to reconcile with the United States to fight Islamic extremists. As a source for this description of Saddam, Draper cites an interview he conducted with Charles Duelfer, the former arms inspector who led the Iraq Survey Group, the mission that was sent to Iraq after the invasion to look for WMD and came up empty. That team also interviewed former Iraqi officials, and Duelfer told Draper that Saddam had viewed the United States as a potential ally. But Draper does not mention the darker conclusion that Duelfer arrived at in his memoir: “I was sympathetic to the president’s strategic decision that Iraq with Saddam was a threat to the United States and containment via sanctions was doomed.” Nor does Draper dwell on the very long section in Duelfer’s final report on Saddam’s strategic intentions. That section begins with the categorical assertion: “Saddam Husayn so dominated the Iraqi regime that its strategic intent was his alone. He wanted to end sanctions while preserving the capability to reconstitute his weapons of mass destruction (WMD) when sanctions were lifted.”

Another team of interrogators (from the Iraqi Perspectives Project, a study run by U.S. Joint Forces Command) also went to Baghdad after the invasion and talked to dozens of Iraqi officials. They, too, concluded that Saddam had been “keeping a WMD program primed for quick re-start the moment the UN Security Council lifted sanctions.” They also noted that Saddam was convinced that none of his opponents “possessed the ruthlessness, competence, or ability to thwart his aims over the long run.”

Draper’s book will solidify prevailing views about the dysfunction, naiveté, and dogmatism of Bush and his advisers.

Saddam was unmoored from reality, as Draper suggests, but he was not harmless and compliant. After the UN Security Council passed a resolution in November 2002 that condemned Iraq’s noncompliance with weapons inspections, Saddam finally allowed inspectors to enter the country. At that point, according to Draper, Americans—not Saddam—obstructed the weapons inspectors. The CIA, he says, held back data on suspected weapons sites and provided confusing information about others. Draper selectively quotes from the memoir of Hans Blix, the chief UN weapons inspector, to highlight Blix’s frustration with U.S. officials but conveys little sense of his discontent with Iraq’s behavior. Blix deemed Iraq’s initial declaration of its arms inventory to be woefully inadequate. As he writes in his memoir, “No significant disarmament issues were solved by the new declaration.” When he and Mohamed ElBaradei, the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, visited Baghdad in January 2003, Saddam refused to meet with them. A month later, according to the British Parliament’s official inquiry into the Iraq war, Blix told a group of European diplomats, “There had been no change in heart, just more activity. Iraq attempted to conceal things.” Blix remonstrated against the American timeline, as Draper accurately notes, and he saw few signs of Iraqi WMD. But he was also frustrated by Saddam’s grudging, belated cooperation and his persistent deviousness, which Draper disregards. Only after the war would it become known that Saddam’s deception stemmed from his desire to deter adversaries, such as Iran, and intimidate domestic foes, such as the Kurds, against whom he previously had used chemical weapons.

Draper does not dwell on Saddam’s behavior because he is convinced that Bush saw inspections as a ruse to go to war, and not as a possible, albeit unlikely, means to ensure Iraq’s compliance with previous UN resolutions and avoid conflict. In a key passage, Draper writes, “The notion of leaving even a defanged Saddam Hussein in power was no longer among Bush’s options.” Yet there is now evidence in the voluminous records of the British parliamentary inquiry that Bush was in fact willing to accept that possibility. At the end of July 2002, when the British sensed that the White House was heading to war, David Manning, Prime Minister Tony Blair’s foreign policy adviser, flew to Washington and talked to Rice. He explained that Blair wanted to be with Bush, no matter what, but that Blair could not go to war for regime change. Saddam’s violations of UN resolutions could serve as a justification for military action, but there had to be a sincere effort to get the inspectors back into Iraq. If Saddam complied, they had to take yes for an answer. Manning then met with Bush, and they arranged a phone conversation between the American and British leaders. Blair told Bush that he did not think Saddam would comply with a new resolution but that if he did, they could not invade. According to Jonathan Powell, Blair’s chief of staff, “The Prime Minister said repeatedly to President Bush that if Saddam complied with the UN Resolutions, then there would not be any invasion and President Bush agreed with him on that.” Blair writes in his memoir, “I knew at that moment that George had not decided.”

Bush, however, did resolve to confront Saddam. In his own memoir, the president recalls saying at a September 7, 2002, National Security Council meeting, “Either he will come clean about his weapons, or there will be war.” Saddam had agency; he had a chance to avoid war. As Blair explained to the British inquiry, “We were giving Saddam one final choice.” If the Iraqi dictator welcomed the inspectors and complied, action would halt. “I made this clear to President Bush, and he agreed.” The Americans understood, Manning said, that “we had given Saddam a get out of jail card if he chose to use it.” But he didn’t, as his behavior during the inspection process revealed.

FEAR FACTOR

Draper minimizes the ongoing sense of threat. Although he stresses the obsessive fear that racked the vice president’s office, he understates the sense of vulnerability that permeated the entire government in the aftermath of 9/11. All of Bush’s advisers capture this anxiety in their memoirs. “It is difficult to put in words the number of reports, and the intensity of those reports, that came in every day,” writes Tenet. An “atmosphere of uncertainty” gripped the White House, “a brooding sense of threat,” remembers Michael Gerson, a speechwriter for Bush. “Every day for those first several days, we expected another strike,” recounts Karen Hughes, Bush’s communications director.

These fears persisted, an important point that Draper elides as he progresses in his narrative. They continued because terrorist attacks did not cease after 9/11. Readers are not told of the more than 700 people who were killed by terrorists during 2002, including 30 U.S. citizens. Draper does not discuss Richard Reid’s attempt to use a bomb in his shoe to bring down an American Airlines flight in December 2001, or the beheading of the journalist Daniel Pearl in early 2002, or the assault on a synagogue in Tunisia in April 2002, or the arrest of Yemeni Americans near Buffalo in September 2002 for their links to al Qaeda, or the bombing of nightclubs in Bali in October 2002 that killed more than 200 people, or the murder of the American diplomat Laurence Foley in Jordan also in October 2002, or the scores of suicide attacks in Israel in 2001 and 2002. Nor does Draper seek to understand why a troubling trio of allegations—that Iraq supported terrorism, that it had WMD programs, and that al Qaeda was seeking WMD—raised concerns among U.S. officials that Iraqi chemical or biological weapons might find their way into terrorists’ hands. Instead, Draper compellingly shows that such allegations were founded on falsehoods that should have been appreciated by Bush’s advisers; they were not appreciated, Draper argues, because Cheney, Libby, and Feith exerted relentless pressure on the analysts to come up with incriminating evidence and because Tenet was leery of disappointing the First Customer.

Employing vivid material from his interviews, Draper seems very convincing. He shows in great detail why intelligence collectors should have been suspicious of the reports emanating from an informant code-named “Curveball,” an Iraqi defector living in Germany who was disseminating false information about Saddam’s chemical weapons. He describes why analysts felt it was futile to voice their misgivings about the information they possessed regarding Iraqi WMD, given their belief that Bush, Cheney, and Rumsfeld had already made up their minds to use military force for regime change. But Draper does not reconcile his conclusions with the exhaustive reports of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and the presidentially appointed Robb-Silberman Commission. These investigations emphasized that intelligence analysts were not bullied into manipulating their findings regarding WMD. However arresting Draper’s evidence may be, he does not deal adequately with conflicting views, such as the one expressed by Richard Haass, who was then the director of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff (and is now the president of the Council on Foreign Relations, the publisher of Foreign Affairs). Haass writes in his memoir, “Not once in all my meetings in my years in government did an intelligence analyst or anyone else for that matter argue openly or take me aside and say privately that Iraq possessed nothing in the way of weapons of mass destruction.”

In their memoirs, almost all of the administration’s top officials—Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Rice, Tenet—emphasize that they went to war for reasons of security, for fear of another terrorist attack, this one conducted with WMD. Draper dismisses these fears and insists that Bush and his advisers invaded Iraq to promote freedom. In making this argument, Draper conflates motives and goals. Having decided to go to war, the president did want to promote democracy, but that was not what drove his decision. Bush went to war because he perceived Iraq as a threat, because he distrusted a dictator who had a track record of defiance, because he felt a sense of responsibility for having been in office on 9/11, and because he was determined to avoid another such calamity. Rice states this clearly: “We went to war because we saw a threat to our national security and that of our allies. But if we did have to overthrow Saddam, the United States had to have a view of what would come next.”

Unfortunately, as Draper vividly describes, Rice and her colleagues never did agree on what would come next, and the postwar phase was a disaster. But that failure raises the question of whether the decision to invade Iraq was unwise from its inception or was proved unwise because of deplorable execution. In Draper’s account, the war was unnecessary. It happened because the president instinctively decided on war almost immediately after 9/11, deluded himself into thinking he was not committed, listened to advisers who fed him misinformation, and claimed an imminent threat when no such threat existed.

Saddam was unmoored from reality, as Draper suggests, but he was not harmless and compliant.

Draper powerfully argues that the war was needless, but a careful reading of the evidence suggests a more complex story. British records, made available in conjunction with the parliamentary inquiry, now reveal that almost all key leaders believed that Saddam would accept inspectors and abide by UN resolutions only when faced with military force. Not only did Bush and Blair think this; so did French President Jacques Chirac and Russian President Vladimir Putin, as well as Blix and British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw. Several of these officials most definitely did not want war, but they did seek Saddam’s compliance and believed it would not be forthcoming unless he was threatened. In fact, Saddam did respond to the threat of force. He reacted slowly, grudgingly opening additional sites for inspection and instructing subordinates and scientists to cooperate. But he still hoped to divide the French and the Russians from the Americans and expected the Americans to back down. Saddam was playing a game of chicken, and he lost. Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, and Rice felt that they had no choice but to go to war once deployments had occurred and they deemed American credibility to be at risk.

Should Bush and his advisers have gotten to this point? Draper argues no; it was foolish, naive, and unwarranted. According to Draper, the president internalized false claims from hawkish advisers that Iraq was linked to 9/11. Draper emphasizes the relentless efforts of Cheney, Wolfowitz, Libby, and Feith to persuade the president of the ongoing connections between Osama bin Laden and the Iraqi Intelligence Service.

But Bush said many times, publicly and privately, that he did not go to war out of a belief that Iraq was responsible for 9/11. Michael Morell, his CIA briefer, told him categorically that there were no links between Saddam and 9/11. Nonetheless, Bush did believe that Saddam represented a looming threat, stemming from his alleged possession of WMD and the prospect that he might hand them over to terrorists, any terrorists. Bush worried about such matters because the international sanctions imposed on Iraq after the Gulf War were eroding, and most advisers and analysts anticipated that Saddam would use his growing revenues to build up his conventional capabilities, restart his WMD programs, and challenge or blackmail the United States or its allies. As the Iraq Survey Group’s report made clear, between 1998 and 2002, Saddam had already been using illegal revenues from smuggling oil to augment his conventional arsenal. Although his military capabilities had been seriously degraded over the previous decade, they were certain to mount once Iraq was freed from sanctions, thereby empowering Saddam to resume his ambitions. And those ambitions were not benign. Captured Iraqi documents published by the Institute for Defense Analyses, a Pentagon research group, reveal that although Saddam had no operational links to al Qaeda, he did have ties to multiple terrorist groups, including the Palestine Liberation Front, Hamas, Egyptian Islamic Jihad, and Afghanistan’s Hezb-e-Islami. He was willing to work with Islamist jihadists. He did wish to challenge American interests and allies. He did seek to support terrorist activities in Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka. He did want to harm Americans.

WHY IT HAPPENED

None of this means that Draper is wrong to condemn the decision to go to war. Although sanctions were eroding and Saddam was bound to become more challenging, he still posed no imminent threat to vital U.S. interests. One could argue—and some did—that Saddam could still be contained, that he could be kept, as Clinton administration officials were fond of putting it, “in his box.” Before Bush embarked on the course of coercive diplomacy, he should have initiated a systematic discussion of the costs and consequences of a military invasion. Instead, his advisers spent endless meetings discussing tactics and goals rather than examining the tradeoffs inherent in a preventive military action that could go terribly awry. For this failure, Draper is rightly critical of the president.

But Bush’s motivations, perceptions, and actions were far more complicated than those portrayed in To Start a War. Bush decided to remove a looming threat, not an imminent threat (although he did conflate the two in his public rhetoric). Inspired by the successful quick overthrow of the Taliban in Afghanistan, he thought he had an opportunity to employ the United States’ overwhelming power to confront a defiant, unrepentant dictator who had WMD and who was dealing with numerous terrorist groups that might inflict harm on the United States or its allies. Bush would not allow Saddam to blackmail the United States or discourage it from using its power to protect its interests in the region. The president wanted U.S. adversaries to know that the country was strong and decisive.

Fear and power, hubris and guilt, not naiveté and dogmatism, inspired the final decision to invade Iraq. The fears were real. The 9/11 attacks were a wrenching experience. Imagine what it was like to have nearly 3,000 people die in a surprise attack after you had been forewarned of al Qaeda’s intention to inflict great harm on Americans. However vague the warnings, imagine the remorse, as well as the anger; imagine the guilt, as well as the lust for revenge. These emotions ooze from the pages of Bush administration officials’ writings. When Robert Gates succeeded Rumsfeld as secretary of defense, he quickly came to realize that the president and his advisers felt, as he put it in his memoir, “a huge sense . . . of having let the country down, of having allowed a devastating attack on America [to] take place on their watch.” Across the Potomac, Carl Ford, a top State Department official at the time, came to the same conclusion. The president and his advisers “were traumatized by 9/11,” Ford later recalled in an essay. He went on: “It happened on their watch. They swore to protect the nation from all threats, foreign and domestic. They failed.” The September 11 attacks, then, bequeathed more than a bloodlust; they bequeathed a sense of responsibility to prevent another calamity.

Draper thinks it was a fantasy to imagine danger emanating from Saddam’s Iraq. But it was not.

Draper thinks it was a contrived fantasy to imagine danger emanating from Saddam’s Iraq. But it was not. To capture the context at the time, consider what was more reasonable: to think on September 10, 2001, that 19 men with knives and box cutters would hijack four planes and destroy the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center and part of the Pentagon, or to think a year later that Iraq might hand over chemical or biological weapons to some terrorist group that might use them against U.S. interests or allies. The latter fear was wrong-headed and exaggerated, but it was not imagined by foolish, ideological advisers and a willful, dogmatic, naive president. It was imagined by officials who had been ridiculed for lacking imagination before 9/11.

When studying the decision to go to war in Iraq, one would do well to consider a comment Haass makes near the end of his memoir. “Although I disagreed with U.S. policy, my disagreement was not fundamental,” he writes. “Earlier, I described my position as being 60/40 against going to war. . . . Had I known then what I now know, that Iraq no longer possessed weapons of mass destruction, then it would have become a 90/10 decision against the war.” In his memoir, Bush more or less acknowledges the same train of thought: that if he had known that Saddam had no WMD, he might have acted differently. Draper has the advantage of knowing what the president did not know, and his interviewees also now know that the war, whose outcome was unclear in early 2003, went terribly wrong. But to capture the true travail of decision-making, one should neither fault a president for lacking the wisdom of hindsight nor judge him on the basis of information he did not possess. Rather, one should illuminate his fears as well as his hubris, his concerns with the nation’s vulnerabilities as well as its power, his remorse over 9/11 as well as his lust for revenge, and his belief that protecting the American people was as important as remaking the world.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to Foreign Affairs to get unlimited access.

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions